How to Have a Truly SEOULACIOUS Time in Seoul

Model @lun4ris.99 lives absolutely SEOULACIOUSLY with real, personal, bespoke experiences anyone can make happen if you avoid the cookie-cutter, beaten path. Because a REAL Seoul Night is usually spent drinking and politicking on a plastic chair often in a NOT “hot place” everybody already knows about, like she has found in Gudi.

Two people sit in the same Anguk cafe on the same Tuesday afternoon. One stays twelve minutes, photographs the signature einspänner from the prescribed angle she learned on TikTok, checks it off her list, and exits to hit four more locations before dinner. The other has been here for three hours with a laptop and a notebook, returns tomorrow at the same time, and by day three knows the ajumma's name and how the morning regulars differ from the afternoon crowd.

Same space. Same week. Completely different Seoul.

One person had a viral moment. The other had a SEOULACIOUS experience.

The difference isn't about being "slow" or "authentic" or finding "hidden gems"—it's about practicing a fundamentally different epistemology. Which is a fancy way of saying: how you know what you know changes what you can know.

At SEOULACIOUS, we've spent seventeen years developing methodologies for accessing the Seoul that TikTok literally cannot see. Not because it's secret or hidden, but because it operates through mechanisms that algorithmic tourism cannot capture. This article gives you the actual methodology—what we call ethnographic touring—and by the end, you'll understand why the algorithm can find you a place, but only you can create the experience.

Welcome to Seoul beyond the reproduction machine.

A Note on What You're About to Read

This article is long. Deliberately, unapologetically long. We're asking you to spend the next twenty to thirty minutes reading something that could have been compressed into a listicle, turned into a TikTok series, or summarized in five bullet points.

We're not doing that.

Here's why: the ethnographic touring methodology we're about to teach you requires slow, sustained attention. It requires you to sit with ideas long enough for them to actually sink in. It requires you to resist the impulse to skim for takeaways and instead let concepts build on each other across time. You can't speed-read your way into understanding how to do slow observation any more than you can TikTok your way into understanding Korean cultural transmission.

Think of this article as slow-cooked content. Not fast food—a considered meal that takes time to prepare and time to consume properly. The length isn't bloat or inefficiency. It's the form mirroring the methodology. We're asking you to practice right now, while reading this, the same kind of slow, deliberate attention you'll need to practice in Seoul.

If you're used to consuming five-minute video summaries or scrolling through quick tips, this will feel different. Let it feel different. Settle in. Make coffee. Give yourself permission to spend real time with these ideas. Because if you can't sustain attention through a long article, you definitely won't sustain attention through three hours of cafe observation.

Do we go to coffee shops to take pictures of the coffee or to drink the coffee? To somehow make snapshots of the experience or actually having an experience unto itself?

This is your warm-up. Consider the act of reading this article your first ethnographic exercise—can you stay present with one sustained argument across multiple sections? Can you resist the urge to jump to conclusions before the framework is fully built? Can you sit still long enough to actually understand something complex?

If yes, you're ready for ethnographic touring in Seoul.

If no, if you're already thinking "too long, didn't read," then the reproduction machine is probably more your speed, and that's fine. But you won't access the Seoul we're about to show you.

Your choice. Keep reading, or don't. But if you keep reading, commit to the time it takes. Slow down. Pay attention. Let the ideas cook.

Now let's begin.

THE POSITIVIST PROBLEM

Let's start with the intellectual architecture behind those lists clogging your Instagram feed. The problem has a name. It's called positivism, and it's been shaping how we think about knowledge since the 19th century, when philosophers decided that science's approach to truth should apply to everything.

Positivism says that only what can be measured is real, only what can be observed counts as knowledge, only what can be verified has value. Therefore: if I can't rank it, list it, or photograph it, does it even exist? This made perfect sense for physics. You can't just feel that gravity works—you have to measure it, replicate the experiment, verify the results. Positivism gave us the scientific method, which gave us modern medicine, space travel, and the internet.

But when we apply positivist logic to cultural experience, something breaks.

They don't call it the "tip of the iceberg" for nothing.

The positivist tourism assumption works like this: if it's worth experiencing, it must be findable through search. If it's findable, it must be listable. If it's listable, it must be rankable. Therefore, cultural value equals what appears in the Top Five. What this epistemology leaves out is everything that can't be quickly measured, easily photographed, or universally verified—which is, let's be honest, most of what makes Seoul actually Seoul.

Now add TikTok's algorithmic logic to 19th-century positivism and you get what we call the reproduction machine. Most tourism TikTokkers don't speak Korean. They source recommendations from other non-Korean-speaking creators, who sourced from earlier non-Korean-speaking creators. Each video is a xerox of a xerox of a xerox. Search "hidden gems in Seoul" and everything's in English, everything's found via prior English content, everything leads back to the same fifteen locations. Content about content about content. Never actual encounter.

This creates a standardized experience protocol that's remarkably consistent: arrive at algorithmically recommended location, order the signature item that's already been photographed ten thousand times, photograph from the established angle that went viral, verify experience against prior content by confirming "it looks just like the video," then exit within fifteen minutes average to hit the next location. Same duration, same consumption pattern, same photo angle, same verification logic. Different people, identical experience.

This isn't tourism anymore—it's content verification. You're not discovering Seoul, you're confirming that Seoul matches what the algorithm showed you.

The Simulation of Experience

If you're having the same, Top 10 List experience as everybody else coming to the place, are you really having your own set of experiences or are you just on a theme park ride?

Here's what happens when a place hits the lists, and this is where French philosopher Jean Baudrillard becomes relevant. To survive the tourist influx, spaces must optimize for the reproduction machine: photogenic signature item becomes required, Instagram-ready interior design becomes required, quick turnover capacity becomes required to handle volume, staff who know the viral angle become required—they'll literally position your phone for you.

Even spaces that started with some kind of organic cultural logic get transformed into what Baudrillard called simulacra—copies without originals, or more precisely, spaces that exist primarily to reproduce the image of themselves that's already circulating. The cafe stops being a cafe with its own cultural function and becomes a prop for reproducing others' experiences. It becomes a simulation of "authentic Korean cafe culture" that's been optimized for Instagram rather than for actual Korean customers.

Baudrillard would recognize what's happening here immediately. The representation precedes and determines the reality. Tourists arrive expecting the Seoul they saw on TikTok, spaces transform themselves to match that expectation, which generates more TikTok content showing the same thing, which brings more tourists expecting exactly that. The simulation becomes self-reinforcing. The map precedes the territory.

And here's the uncomfortable question: if you're following those lists, are you experiencing actual Korean culture or just the tourist version? Maybe you are getting something real. But maybe—probably—you're getting the simulation that's been constructed specifically for algorithmic circulation. The Korean cafe that's been optimized to photograph well has already ceased being primarily Korean and has become primarily photogenic. The distinction matters.

We've documented this process across Seoul neighborhoods for seventeen years. Young tourists' aesthetic consumption creates economic pressure that homogenizes the very qualities that made spaces culturally productive in the first place. What starts as organic cultural practice becomes performance, then becomes simulation, then becomes the only reality that remains accessible.

The linguistic tell reveals this. Korean reviewers often write things like "어떻게 설명해야 할지..." which means "I don't know how to explain this but..." This phrase marks experiences that exceed categorical expectations—moments when something about a place resists the frameworks you brought to understand it. English-language tourism content systematically filters these out because the creators literally cannot access the linguistic context where illegibility becomes visible. The Seoul that makes Koreans struggle to explain—the Seoul that operates through tacit knowledge, embodied practice, and temporal variation—stays invisible to the reproduction machine.

This is the positivist problem: the assumption that only conscious, articulable, photographable, reproducible knowledge constitutes valid cultural understanding. But what if the most important cultural transmission happens precisely through what can't be measured?

THE ILLEGIBLE KOREA

Let's talk about illegibility as a concept, because it's central to everything that follows. Something is illegible when it resists the frameworks we bring to read it. It doesn't mean invisible or hidden—it means it exceeds or contradicts the categorical systems we're using to make sense of it.

Korean culture has layers of illegibility built into it. There's the obvious linguistic illegibility if you don't speak Korean, but that's not what we're talking about. We're talking about cultural practices that resist easy categorization even when you can understand the words being used. That "어떻게 설명해야 할지..." phrase signals this perfectly—"I don't know how to explain this but..." The speaker is struggling with categorical frameworks, not vocabulary.

Illegibility appears at multiple scales. There are illegible spaces—places that can't be cleanly classified as one type of business or function. There are illegible neighborhoods where multiple incompatible urban systems collide in the same physical location. There are illegible cultural practices that don't map onto Western frameworks even when described carefully. There's illegible knowledge that operates below conscious articulation—the embodied understanding that transmits through practice rather than instruction.

And crucially, there's geographic illegibility. Korea outside Seoul remains largely illegible to tourism not because it's inaccessible but because the frameworks tourism uses to make Korea legible are overwhelmingly Seoul-centric. The reproduction machine can't process Jeonju or Gwangju or Jeju's mountain villages because they don't fit the urban modernity narrative that Seoul represents.

The illegible isn't better or more authentic than the legible. It's just different, and it requires different epistemologies to access. Positivist tourism optimizes for legibility—for what can be quickly categorized, easily photographed, and universally verified. Ethnographic touring optimizes for encountering the illegible—for what reveals itself only through duration, what resists quick categorization, what operates through tacit knowledge and embodied practice.

When we advocate for ethnographic touring, we're advocating for methods that can engage with illegibility rather than demanding everything become legible on our terms. That's what the notebook and camera are for—not to capture and categorize, but to document and sit with things that resist easy understanding.

THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL ALTERNATIVE

By Tangopaso - Paris au cours des siècles, de Jacques Wilhelm, 1T 1961, Éditions Hachette, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7918777

This brings us to a bigger question—what philosophers call epistemology, which means how we know what we know. Epistemology isn't about what you know, which is just information. It's about the methods you use to produce knowledge in the first place, and those methods determine what becomes knowable at all.

Consider that algorithmic positivist tourism produces knowledge by searching, verifying, photographing, and reproducing. The outcome is content, spatial coverage, list completion. This epistemology produces a Seoul of verified moments—reproducible, photographable, rankable. It's not wrong, it's just radically incomplete.

Contrast this with ethnographic observational practice, which produces knowledge through participant observation, systematic documentation, and field notes. The outcome is understanding of how spaces actually operate across time. This epistemology produces a Seoul of social rhythms—temporal patterns, unwritten rules, spatial logic that reveals itself only through duration and attention.

Then there's what we might call embodied knowing—knowledge produced through repetition, regularity, and becoming a temporary local. The outcome is felt understanding that lives in your body rather than in words. This epistemology produces a Seoul of lived experience—how the city operates in your muscles and habits, through your movements, via habituation rather than conscious learning.

The first epistemology gets you content. The second gets you knowledge. The third gets you Korea.

Most tourists never escape the first epistemology because they don't know the other two exist. The reproduction machine presents itself as the only valid way to encounter Seoul. Lists become naturalized as the form that cultural recommendations must take. But what if there's a hundred-fifty-year-old methodology for encountering cities that positivism literally cannot capture? What if you could practice it with nothing more than a notebook and three hours?

Welcome to ethnographic touring.

BE BAUDELAIRE IN BUKCHON

In 1863, Charles Baudelaire published an essay called "The Painter of Modern Life" that would change how we think about urban experience. But to understand why this mattered, you need to understand what was happening to Paris at that moment.

Baron Haussmann was tearing down medieval Paris and rebuilding it as a modern metropolis—wide boulevards replacing narrow alleys, grand department stores appearing where small shops had been, gas lighting transforming night into day, railway stations bringing unprecedented movement and mixture of classes. Paris was becoming the first truly modern city, and nobody quite knew what that meant or how to look at it. The speed of transformation was bewildering. Old social orders were collapsing. New types of people were appearing on the streets—the prostitute, the dandy, the ragpicker, the flâneur himself.

Everything was new and strange and worthy of wonder, but most people were too busy rushing through it to actually see it. The city was becoming illegible to its own inhabitants through the sheer velocity of change.

Baudelaire described a figure he called the flâneur—someone who wandered these transforming Paris streets with no instrumental purpose, observing urban life with the systematic attention usually reserved for scientific study. The flâneur wasn't shopping or commuting or going anywhere in particular. He was watching the emergence of modernity itself. And then writing down what he saw.

The flâneur walked aimlessly while others rushed purposefully, observed street life systematically across different times and conditions, took detailed notes on patterns in daily cultural practice, and resisted capitalism's time-optimization logic by spending hours "doing nothing." He turned urban observation into art and social documentation.

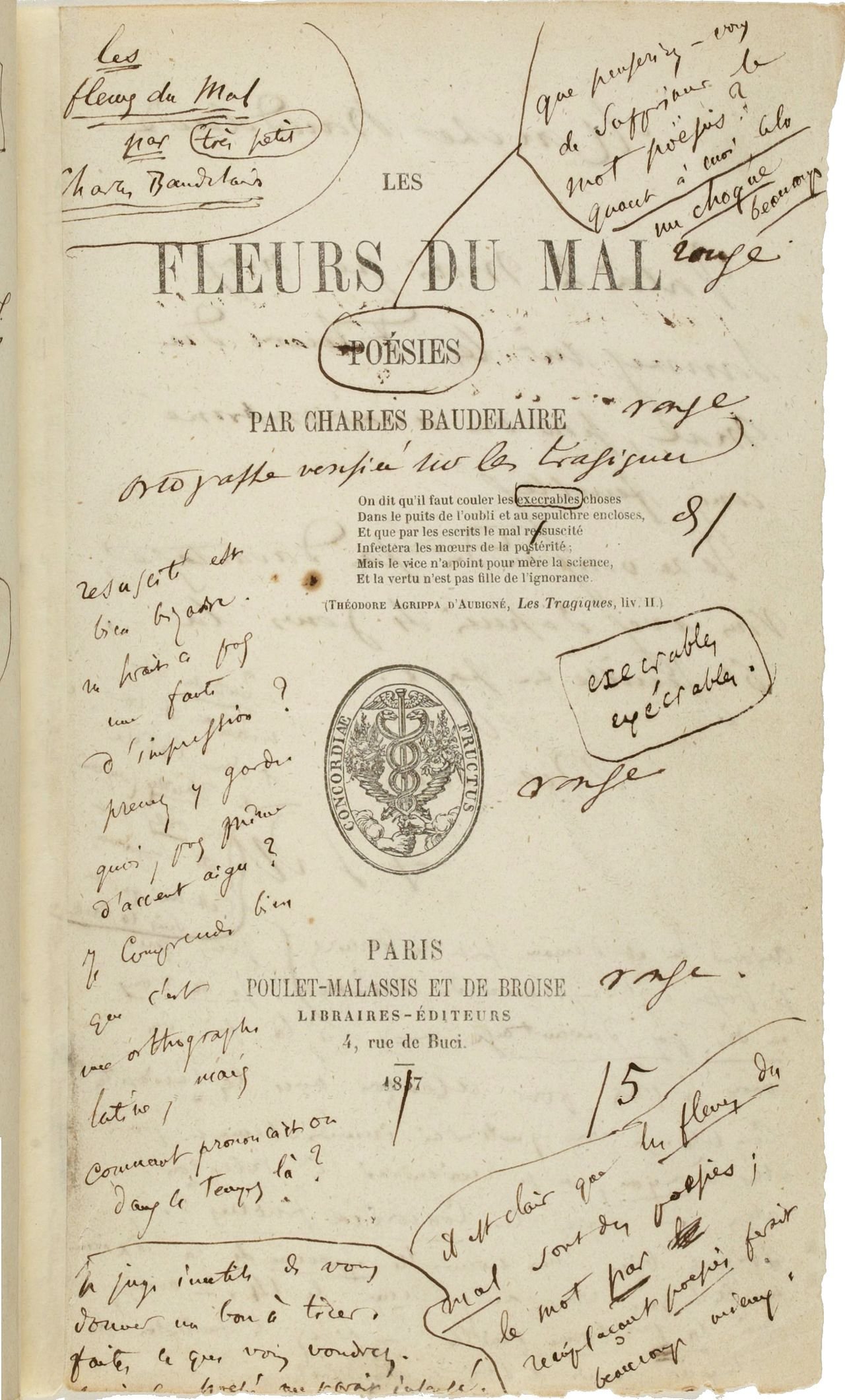

Baudelaire himself practiced this methodology. His poetry collection "Tableaux Parisiens" wasn't just pretty verse—it was urban ethnography. He documented how different classes moved through streets, what vendors sold and how they sold it, how public space got negotiated across different populations, the texture and rhythm of modern urban life, and moments when the ordinary became strange. Baudelaire's urban poetry was actually ethnography—systematic documentation of cultural life that conventional journalism and academic study were missing.

What we'd like to imagine what Baudelaire would be doing on his days in Paris.

He captured Paris by paying attention differently. Not as consumer or commuter, but as someone who understood that the most important urban knowledge comes from duration, repetition, and systematic observation of the everyday.

Now imagine yourself doing exactly this. Not reading about Baudelaire—being Baudelaire. In Bukchon instead of Boulevard Saint-Germain, in Yeonnam-dong instead of the Latin Quarter, documenting Seoul's contemporary urban rhythms the way he documented Paris's 19th-century modernity.

You're in a Mangwon cafe with a notebook. You've been here three hours. You're watching the morning regulars arrive—an elderly man who takes the same corner table at exactly 10am, a woman who brings her own elaborate tea setup in a wooden box, university students who push two tables together and spread laptops and textbooks across both. You're writing down what you see. Not casually, not "journaling"—systematically documenting patterns in spatial practice.

This is ethnography. In academic language, it's systematic documentation and analysis of cultural practices through participant observation. In plain language, it means paying really close attention to how people actually live, writing down what you notice, looking for patterns, checking if your patterns hold across different conditions, and generating knowledge that can't be accessed any other way.

Standard tourism says maximize locations and minimize time per location. Ethnographic touring says minimize locations and maximize time per location. You're not going to "see more of Seoul" through ethnographic touring. You're going to know one part of Seoul in ways that tourists literally cannot, because you'll be using a different epistemology to produce a different kind of knowledge.

Paris changes! but nothing of my melancholy as lifted. New palaces, scaffoldings, blocks, old outer districts: for me everything becomes allegory and my cherished memories weigh like rocks.

Then too, before the Louvre an image presses down on me: I recall my great swan with his crazy movements, as if in exile, ridiculous, sublime, gnawed by ceaseless craving! and think of

you, Andromache (from a great spouse’s arms, fallen — mere chattel — under superb Pyrrhus’s thumb) bent in ecstasy over an empty tomb, Hector’s widow, alas! wife of Helenus!

I think of a negress, wasted, consumptive, trudging the mud, wild eyed, looking for faraway palms of glorious Africa behind an immense wall of fog; of

whoever has lost what can never be found again, ever! of those steeped in tears, suckling Pain like a kind she-wolf; of starved orphans dried like flowers!

So in the forest of my mind’s exile an old Memory sounds a clear note on the horn! I think of sailors lost on desert islands, of prisoners, of the vanquished! . . . and of still others!

— The Flowers of Evil, “Parisian Scenes,”

trans. Keith Waldrop. Reproduced with the permission of Keith Waldrop.

Charles Baudelaire

The Notebook and Camera Practice

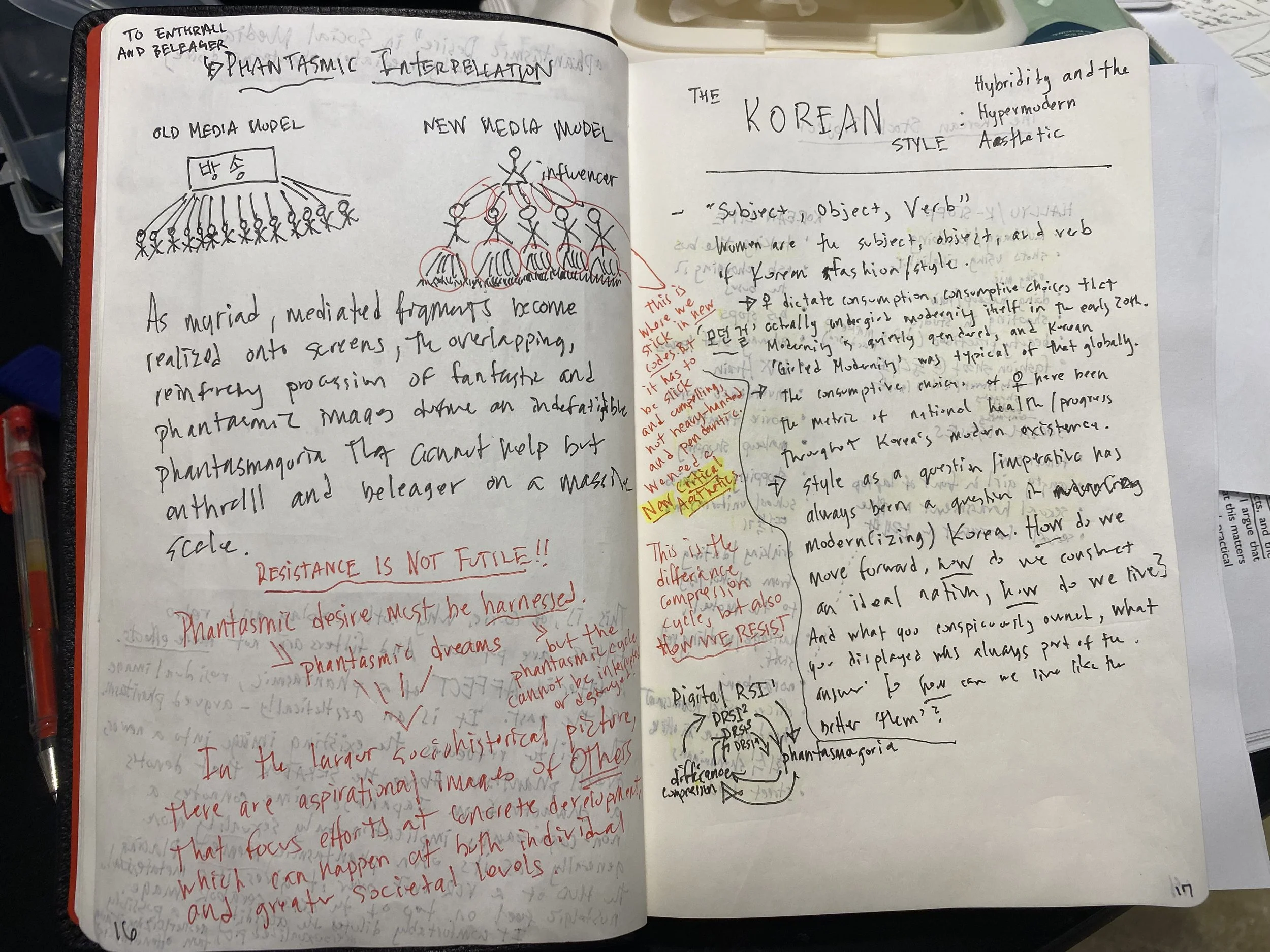

So you're sitting in that cafe. Notebook open, phone within reach. What are you actually documenting?

Start with spatial practices—how people use space. Watch where people sit and notice if patterns emerge. The corner tables seem reserved for regulars who stay long. The counter seats have high turnover, people alone with phones, fifteen to thirty minute stays. The window table attracts laptop workers who've been here since you arrived two hours ago. Write this down. Not impressionistically—specifically. "10:47am Tuesday, Table 6: Four university students, all with laptops plus textbooks. They've been here since I arrived at 9:30am. Each ordered one americano. They've refilled their water bottles twice from the self-serve station. Staff hasn't asked them to order more—seems completely normal to nurse one coffee for hours."

And photograph it. Not for Instagram—for documentation. Your phone camera is part of your ethnographic toolkit now. Take a wide shot showing the spatial arrangement of tables. Photograph the corner where regulars sit versus the counter's transient population. Capture the material details—the self-serve water station that enables long stays, the table configuration that allows students to spread out. These images aren't content, they're evidence. They'll help you remember spatial details when you're writing up your observations later, and they'll reveal patterns you didn't consciously notice while taking them.

You're capturing the spatial logic of the cafe—how different populations use the same space for different purposes, operating on different temporal rhythms. This is ethnographic data. No one else has this. TikTok cannot generate this because TikTok photographs for aesthetics, for verification. You're photographing for analysis, for memory, for documentation of patterns.

Move to social rhythms—patterns across time. Return tomorrow, same cafe, same time. Notice what stays constant. The elderly man arrives at 10am again, exactly. Same table. Staff greets him by name: "안녕하세요, 사장님." He stays exactly thirty minutes, you time it. Same routine as yesterday. The woman with the tea setup appears again too. But the afternoon crowd will be different—you noticed yesterday that after 2pm, tourists started appearing. Shorter stays, photographing drinks, English conversations. Write it all down. "Day 3, Thursday: Pattern emerging. 9:30-11am equals regulars. Older, know staff, same orders, same tables. 11am-1pm equals laptop workers. Younger, long sessions. After 2pm equals tourists. The space has at least three distinct populations operating on different temporal rhythms, all sharing the same physical location."

What you're documenting is how this space operates as temporal infrastructure for different populations—something completely invisible to single visits. The cafe isn't one thing. It's multiple things depending on when you observe it.

Now pay attention to material culture. What do people bring with them? You notice that half the morning regulars bring their own cups or thermoses. Staff fills them without comment, charges regular price. This isn't some eco-statement—it just seems normal here. Photograph one of these transactions discreetly. Photograph the woman's elaborate tea setup when she's not looking directly at the camera—the wooden box, the varieties of tea, the small cups, the timer. These images document material practices that words struggle to capture fully.

The woman with the tea setup isn't even consuming the cafe's product. She's consuming their time and space. The cafe is selling infrastructure, not just coffee. Look at the walls. Mix of Korean literature, architecture books, what looks like the owner's personal vinyl collection. Photograph the bookshelves—later you might be able to read some titles and understand what kind of cultural work this curation is doing. Not designed for Instagram. Designed for people who stay. One wall has rotating art that changed between Day 1 and Day 3. Someone curates this. Photograph it on both days. The change itself is data.

Your camera and notebook work together. The notebook captures observations, thoughts, patterns you're seeing. The camera captures visual evidence you'll need when writing up your field notes, and it documents details you'll forget—the exact arrangement of books, the specific art on the walls, the material setup of that tea ceremony.

Even if you don't speak Korean fluently, observe language and interaction. How do customers order? Young customer at counter uses very casual speech to barista, lots of "요" endings but relaxed tone. Barista responds formally but friendly. This is the third time you've seen this customer—seems regular but maintains some formality. Different from American coffee shop culture where regulars get very casual very fast. Social hierarchy seems maintained even in repeated interaction. Or maybe it's about age? The elderly man uses even more formal speech and gets very formal responses. The sound level stays quiet even when the cafe fills. Korean cafe culture seems to value ambient quiet—people moderate their voices. One tourist group yesterday was noticeably louder, got glances. Write it down.

And crucially, document your own embodied experience. You're not an objective observer—you're a participant. Your changing relationship to the space is data. Day 1 you felt very aware of being foreign, chose a corner table to be less visible, ordered the safest item, kept headphones in, stayed two hours but felt like you should leave. Day 2 you chose a better work table near the window with better light, ordered something you actually wanted, and the barista nodded recognition when you entered—small but noticeable. You stayed the full three hours and felt less performative. Day 3 you arrived at "your time," 9:30am. The barista started making your order before you finished requesting it. You're in the morning regular rhythm now. Your body feels different in the space—less like "being in a Korean cafe" and more like "working at my cafe." Less performance, more inhabitation. This is embodied knowledge. You didn't consciously learn this. You absorbed it through repetition.

What you're documenting here is how embodied integration happens through temporal repetition—your own transformation from tourist to temporary local.

Expanding the Radius

In this day and age, it's easy and safe to get lost on purpose if you just let yourself wander and lose yourself and then later, be saved by the GPS on your phone.

After three days of deep ethnography at your anchor space, expand. Pick a weekday morning when it's less crowded and walk aimlessly for minimum two hours within five hundred meters of your cafe. No destination. Just observation. This is the Baudelairean walk.

Notice spatial relationships. What's near your cafe? Residential buildings, commercial spaces, or both mixed together? Who else are the regulars in the neighborhood at other cafes, shops, street vendors? How do different types of spaces relate to each other? Where do you see the same people across different locations? Write it down. "Yeonnam Thursday morning walk, 10am to noon: Five hundred meter radius reveals mostly residential—lots of villas, older buildings—but commercial bleeding in along main roads. Recent cafes and restaurants clearly newer construction or renovations. Spotted three people I recognize from my cafe at a different cafe two blocks away. Regulars have circuits, not single locations."

Notice movement patterns. How do people move through the neighborhood? What paths get used repeatedly? Where do different populations cluster? What streets feel residential versus commercial versus mixed? The park has a totally different population—young parents, elderly doing exercises, tourists photographing. Different temporal rhythm, people pass through rather than stay. The alley market near the subway has older vendors, local residents shopping for dinner ingredients. Korean only, no English, no tourists visible. This is the residential infrastructure the cafes depend on but tourists never see.

Write it down: "The neighborhood operates as a system. Tourist Seoul—the cafes, the restaurants—is supported by residential Seoul—the markets, the services—that remains invisible if you only go where Instagram tells you."

What you're capturing is the neighborhood as layered interface, where multiple urban systems operate simultaneously in the same physical space. This is invisible to anyone who just hits the viral locations and leaves.

The way we like to think of coffee and productive thought.

On Slow Time (And Why Three Hours Isn't Weird)

Let's address something directly: spending three hours in a single cafe might feel uncomfortable at first. You might feel like you're "wasting time" or being inefficient. You might think you should be hitting more locations, checking off more things, maximizing your Seoul experience by stacking and packing multiple visits into the same time block.

Resist this impulse. Understand what's actually happening when you choose slow time over stack-and-pack efficiency.

Those several experiences you could squeeze into three hours—the viral cafe, the photogenic bookstore, the Instagrammable dessert place, the trendy boutique—are what we might call interchangeable experiences. They're fun, they're aesthetically pleasing, they generate content. But here's what you won't notice until it's too late: you could have these exact experiences in Tokyo, in Taipei, in any globally connected city with similar algorithmic tourism infrastructure. The aesthetics change slightly, the language on the signs is different, but the fundamental experience is the same. Fast-moving, content-generating, verification-based tourism that produces memories you'll struggle to distinguish from each other six months later.

The slow experience—three hours observing a cafe's social rhythms, documenting how regulars differ from tourists, noticing how the space transforms across the day, feeling your own body relax into temporary regular status—this literally cannot happen anywhere else. It's situationally specific. This particular cafe in this particular neighborhood during these particular days when you happened to be there. The knowledge you're producing is non-transferable precisely because it required duration and presence and sustained attention in one location.

Six months later, you won't remember the aesthetic details of five different cafes you visited for twenty minutes each. Those experiences blur together. But you will remember the morning regular who arrived at exactly 10am for three consecutive days. You'll remember how your body felt different on Day 3 compared to Day 1. You'll remember the spatial logic you discovered through sustained observation. You'll remember what you learned about Korean social practices through watching rather than just consuming.

This is why slow time isn't weird—it's valuable in ways that stack-and-pack experiences simply cannot be. You need both kinds of time, honestly. Some fast-moving exploration to get a sense of a neighborhood's scope and variety. But also significant slow time where you actually inhabit spaces rather than just verifying them.

Otherwise you'll have another set of Seoul experiences that you could have had in any other place on the planet. And you won't fully realize this until you're home trying to explain what Seoul was actually like, reaching for specific memories and finding only generic ones. By then it's too late.

The realizations that come during slow experiences—the patterns you notice on Day 3 that were invisible on Day 1, the embodied understanding that accumulates through repetition, the knowledge that reveals itself only through duration—these become the most memorable parts of your Seoul visit. These are what you'll actually talk about when friends ask what Seoul was like. Not the stack-and-pack content verification, but the slow ethnographic observations that taught you how the city actually operates.

So yes, spend three hours in one cafe. Sit still. Watch. Write. Photograph systematically. Let the time feel long. That's the point.

Writing It Up

Here's something crucial: your field notes and photographs aren't just for you. After a week or two of observation, sit down and write up what you've discovered. This doesn't need to be academic—it can be a blog post, an extensive Facebook post, even a long Instagram caption if that's your platform. The act of writing forces you to synthesize patterns you've been documenting and articulate observations that were floating loosely in your notebook.

Use your photographs to illustrate what you're describing. That image of the morning regular's thermos transaction shows infrastructure economics better than paragraphs of explanation could. The shot of the tea ceremony setup demonstrates how people use cafe space for personal ritual. The before-and-after photos of the rotating wall art prove curatorial attention to detail. The wide shot showing table arrangements makes spatial segregation of populations visible.

This isn't about going viral or getting likes. Writing up your ethnographic observations with photographic evidence serves several purposes. First, it consolidates your own understanding—you discover what you learned by trying to explain it to others. Second, it creates a record you can return to later when patterns become clearer across multiple neighborhoods or visits. Third, it demonstrates to yourself that you actually produced knowledge, not just "had experiences." You did research. You have findings. You can share them.

Think of it as your own small contribution to understanding how Seoul actually works, distinct from the reproduction machine's endless content cycle. Someone searching for real knowledge about Yeonnam-dong might stumble across your careful documentation and learn something true instead of something viral. That matters.

The Analog Pleasure (And Digital Alternatives)

The new, analog fetish. The fun of the Tactile.

Here's something we need to acknowledge: you could also do ethnographic observations via short video notes—quick voice memos documenting what you're seeing, brief video clips capturing spatial arrangements or interactions, TikTok-style snippets that you compile later into longer video essays. This is different from the content we've been critiquing because you're using the format for systematic documentation rather than viral verification. You're building an archive of observational clips that serve analysis rather than aesthetics.

But we strongly suggest you keep things as traditional as possible and write in a paper notebook.

There's something about the analog method that matters beyond just functionality. Go to one of Seoul's many excellent stationary shops—every major neighborhood has them, often multiple floors of beautiful paper goods—and buy yourself a proper notebook. Maybe something Korean-made, possibly fancy, definitely something that feels good to hold and write in. This becomes part of your ethnographic practice, part of your embodied engagement with Seoul. You're consuming local material culture while documenting local cultural practice.

And then there's what we might call the analog fetish, which is genuinely fun and valuable. After spending days doing extensive writing in your locally purchased notebook, the tactile feel of the ink marks and deep scratches on the paper become evidence of reality-grounded thinking. The physical weight of accumulated pages. The way your handwriting changes across days as you get tired or excited or focused. The coffee stains from your three-hour sessions. The slight warping of pages from humidity. The way certain observations got crossed out and rewritten when you realized you'd misunderstood something.

All of this is data about your process, but it's also just pleasurable in a way that digital note-taking isn't. The notebook becomes an artifact of your Seoul research, not just a record of it. You can flip back through pages and remember not just what you wrote but where you were sitting when you wrote it, how the cafe sounded that day, what you were thinking about. The physical object holds memory in ways that cloud-stored text files don't.

And honestly, in an age of algorithmic everything, there's something quietly radical about sitting in a Seoul cafe with a paper notebook and a pen, hand-writing observations about spatial practices and social rhythms. You're refusing the digital-first logic that assumes everything worth documenting should be instantly shareable, immediately uploadable, optimized for platform circulation. You're doing slow analog documentation in fast digital Seoul, and that refusal is itself meaningful.

So yes, you can supplement with video notes if that helps your process. But make the notebook central. Make it analog. Make it physical. Buy it in Seoul. Write in it extensively. Let the physical object become part of your ethnographic practice and part of what you bring home—not just the knowledge you produced, but the material artifact that holds evidence of your reality-grounded thinking.

Which are you gonna do? Stay in an Insta/Tok grid or go OFF the grid?

Becoming the Ethnographer

After two weeks of this practice, what do you have? Not fifty Instagram locations checked off. Not maximum spatial coverage or reproduced viral content. You have ethnographic data—systematic documentation of cultural practices that cannot be reproduced because it's uniquely situated in your temporal and spatial encounter, that cannot be found in lists because it operates below algorithmic visibility, that cannot be photographed because it's tacit and relational and temporal, and that cannot be quickly verified because it requires duration and repetition to access.

You have field notes containing patterns that TikTok tourists literally cannot see because you used a different epistemology and therefore produced different knowledge.

And here's the beautiful part: you're not just "being slow" or "taking your time." You're practicing a hundred-fifty-year-old methodology with academic legitimacy. You're doing what Baudelaire did in Paris, what urban sociologists do in field research, what anthropologists do in ethnographic study.

You can say: "I spent two weeks practicing participant observation in Yeonnam-dong, documenting social rhythms and spatial practices through systematic field notes, in the tradition of Baudelaire's urban ethnography adapted to Seoul's contemporary interface conditions."

This is not tourism. This is research. Your three-hour cafe sessions aren't wasting time—they're fieldwork. Your notebook isn't a diary—it's ethnographic documentation. Your repeat visits aren't inefficiency—they're methodological rigor. You're not a slow tourist. You're an urban ethnographer.

GOING DEEPER

If you want to enhance your ethnographic practice, try bringing an unusual object with you—something portable that creates slight juxtaposition, like a vintage camera or a traditional Korean item. Place it on your cafe table and see what conversations it starts. Different spaces reveal different aspects of themselves through how people respond to the same unexpected element.

Or systematically vary one condition in your repeat visits. Visit your anchor space on a weekend after documenting it on weekdays, or go in the evening after studying it in the morning. The "same" space becomes multiple spaces depending on temporal context, and tracking these variations reveals how Seoul spaces serve different functions for different populations.

And pay attention to what you feel physically, not just what you see. How does your body move through a space? What postures does it encourage? Notice that certain cafes make you hunch slightly, that you can hear conversations from several tables away, that the temperature feels deliberately cool. These design decisions operate on bodies below conscious awareness. Your body is an ethnographic instrument—use it deliberately.

PREPARATION AND PRACTICE

My madman notebook scribblings.

Before you arrive in Seoul, do some intellectual preparation. Read Baudelaire's "The Painter of Modern Life"—it's available free online, forty pages, and it helps you understand that you're not inventing this methodology, you're part of a hundred-fifty-year tradition. The flâneur wasn't wasting time. Neither are you. Learn basic Korean, even just twenty phrases, because it changes what you can access. You don't need fluency, you need enough to signal respect and openness. Even detecting "어떻게 설명해야 할지..." without fully understanding it tells you something important is happening.

Choose your neighborhood before you arrive. Don't pick five, pick one. Research its history, what's developing there, who lives there. Understand what interface types might be colliding in that space. Read Korean blogs about the area if possible—Google Translate is your friend. And adjust your expectations consciously. You will not see all of Seoul. You will know one part of Seoul in ways tourists cannot. This is a trade: breadth for depth. Make the trade consciously.

For practical preparation, choose a physical notebook rather than digital because the tactile act of writing changes observation quality. Pick something you actually like writing in with a pen you enjoy using, because you'll be writing extensively. Make sure your phone has adequate storage for photographs—you'll be taking hundreds, not for Instagram but for documentation. Think of yourself as a documentary photographer, not a content creator. You're gathering visual evidence to support your written observations.

Schedule three-hour blocks minimum and build in repetition by planning to return to the same places. Don't optimize for maximum locations. Optimize for maximum depth in minimum locations. Identify what work you'll actually need to do while there and plan spaces around functionality rather than photo potential. Bring your laptop, chargers, work materials. You're living temporarily, not touring.

Once you're in Seoul, establish your field site during days one through three. Choose one anchor space in your chosen neighborhood where you can comfortably work for three-plus hours and return at the same time for three consecutive days, somewhere with regular Korean clientele rather than just tourists, preferably somewhere you can get a similar table each visit. Neighborhood cafes in Mangwon, Seongsu, Yeonnam, or Haebangchon work well—not the viral ones but the ones where locals actually work.

Arrive at a specific time on Day 1. Get coffee. Settle in for minimum three hours. Open your notebook. You're now doing participant observation—both in the space as a customer and studying the space as an ethnographer. Document spatial practices, social rhythms, material culture, language and interaction, and your own embodied experience using the protocols described earlier. Return Day 2 same time, same approach, noting what stays constant and what changes. By Day 3 you should start seeing yourself absorbed into regular rhythms and feeling the space differently in your body.

Days four through seven, expand the radius. Take Baudelairean walks for minimum two hours within five hundred meters of your anchor space with no destination, just observation. Map the spatial relationships, movement patterns, and temporal variations. Document how the neighborhood operates as a system rather than as isolated Instagram locations.

If you have more time, days eight through fourteen can involve comparative ethnography. Choose two or three similar spaces in the same neighborhood and apply the same observation protocol, looking for what's universal to the neighborhood versus specific to each space, how similar spaces differentiate themselves, and what variations exist within what looks like the "same" thing. This reveals functional differentiation within apparent similarity and how the neighborhood's cultural ecology actually operates.

THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL STAKES

Let's zoom out. We're not just teaching you how to visit Seoul differently. We're teaching you epistemological plurality—the understanding that there are multiple valid ways of knowing, and they produce fundamentally different kinds of knowledge.

Positivist algorithmic tourism produces Seoul as consumer product through methods of searching, verifying, and photographing to generate content and coverage. Ethnographic observational practice produces Seoul as cultural system through participant observation and systematic documentation to generate understanding of how Seoul operates. Embodied phenomenological immersion produces Seoul as lived experience through repetition and regularity to generate non-verbal cultural transmission.

These aren't different styles of tourism. They're different epistemologies that produce different ontologies. Ontology means what exists, and epistemology determines what can exist for you because it determines what you can know.

If we accept that only measurable, rankable, reproducible phenomena constitute valid knowledge, we miss how Korean culture actually transmits. K-pop cover dance operates through kinesthetic knowledge that you can't listify your way into. Street fashion transmits through photo-sartorial mechanisms operating below conscious articulation. Cafe culture functions as spatial infrastructure embedded in social practices of duration and regularity. Neighborhood rhythms reveal themselves as temporal patterns visible only across multiple visits. None of this appears in Top Five lists because positivist epistemology literally cannot capture it.

There's also a political dimension here. Who profits from positivist tourism? Platforms extract value through content while viral spaces bear economic pressure to homogenize, which removes what made them culturally productive in the first place, and local populations get displaced by tourist optimization. What kind of Seoul becomes visible through this epistemology? One where photogenic doesn't equal meaningful, viral doesn't equal culturally significant, English-accessible doesn't equal actually Korean, and reproducible doesn't equal valuable.

Positivist tourism isn't neutral. It's a specific epistemology that serves platform capitalism while eroding the cultural conditions it claims to celebrate. Baudelaire understood this in 1863 when industrial capitalism demanded time efficiency, instrumental purpose, measurable productivity, and optimized movement. Flânerie offered time abundance, observational purpose, unmeasurable knowledge, and aimless wandering. Baudelaire's contemporaries thought he was wasting time, but his "wasted time" produced knowledge of Parisian urban life that instrumental observation missed.

He was doing ethnography before ethnography had a name. And you're doing the same thing—just in Seoul instead of Paris, with the added complexity of algorithmic tourism instead of industrial capitalism.

THE SEOUL-CENTRIC PROBLEM (A Necessary Acknowledgment)

There's an irony we need to address. This entire article—this entire magazine, frankly, given we're called SEOULACIOUS—is relentlessly Seoul-centric. We're critiquing positivist tourism's limitations while simultaneously reinforcing one of tourism's biggest blind spots: the assumption that Korea equals Seoul.

Tourism infrastructure and algorithmic recommendation systems overwhelmingly privilege the capital. Search "things to do in Korea" and you get Seoul. Search "Korean culture" and you get Seoul. The reproduction machine we've been dissecting doesn't just reproduce experiences within Seoul—it reproduces Seoul itself as the only Korea worth visiting. Most tourists never leave the capital, or if they do, it's a day trip to the DMZ or a weekend in Busan that still follows the same positivist logic we've been critiquing.

Meanwhile, there's Gwangju and Daegu and Jeonju and Andong and hundreds of smaller cities and rural areas where Korean life unfolds in ways that Seoul simply doesn't capture. There's Jeju's distinct cultural history and the particular character of Honam region and the fishing villages along the east coast and the agricultural communities that still structure much of the peninsula's social life. There's Korea outside the metropolitan sprawl, and it's as invisible to Seoul-based tourism as illegible experiences are to Top Five lists.

So yes, we're advocating for ethnographic touring, but we're doing it in a fundamentally Seoul-centric frame. The methodology works elsewhere—you could absolutely practice Baudelairean observation in Jeonju's hanok village or systematic field documentation in Busan's Gamcheon or participant observation in Gyeongju's neighborhoods. The epistemological principles transfer. Pay attention across time, document patterns, let duration reveal what quick visits miss, become a temporary regular somewhere. This works in Mokpo just as well as it works in Mangwon.

But the fact remains that by centering Seoul, even in an article critiquing tourism's limitations, we're participating in the same geographic hierarchy that makes Korea legible primarily through its capital. Tourism plays into this obviously—the infrastructure, the English-language content, the algorithmic recommendations all funnel people toward Seoul. But we're doing it too by focusing our seventeen years of research primarily on Seoul's neighborhoods, by teaching Seoul Space Lab instead of Jeonju Space Lab, by documenting Seoul Fashion Week instead of regional creative scenes.

The really illegible Korea—and remember, we just spent a section defining illegibility as what resists the frameworks we bring to understanding—might be precisely what exists outside the capital. Not as "traditional Korea" in touristic opposition to "modern Seoul," which is just another simulation, but as actually different regional cultures with their own rhythms and practices and spatial logics that don't map onto Seoul's particular urbanism. This is geographic illegibility operating at the largest scale.

We don't have a solution to this except to acknowledge it. SEOULACIOUS remains Seoul-centric because that's where our research has been concentrated and where we have the depth of knowledge to write with authority. But if you're reading this and thinking "what about the rest of Korea," you're absolutely right. The ethnographic methodology we're advocating could and should be applied elsewhere. The epistemological critique of positivist tourism applies to how Korea as a whole gets packaged for consumption, not just its capital.

So take the methodology, take the notebook, take the three-hour observation sessions and the Baudelairean walks and the systematic field documentation—and maybe don't just use them in Seoul. Maybe practice them in Gangneung or Suncheon or Yeosu. Maybe the most SEOULACIOUS thing you could do is refuse Seoul-centrism entirely and document the Korea that exists beyond algorithmic visibility and beyond the capital's gravitational pull.

That would be truly ethnographic. That would be genuinely counter to the reproduction machine. And that would require intellectual honesty about our own limitations, which this acknowledgment attempts to provide.

CONCLUSION: THE NOTEBOOK AND THE CAMERA

The algorithm can find you the Top Five cafes in Yeonnam-dong. It cannot teach you to sit for three hours with a notebook and a camera, documenting the social rhythms of a Seoul cafe the way Baudelaire documented Paris cafes in 1863. It cannot give you field notes and photographs that together capture how the morning regular crowd differs from the afternoon tourist influx. It cannot produce ethnographic knowledge about how Korean cafe culture operates as temporal infrastructure for different populations. It cannot show you how your body learned to inhabit a space differently through repetition.

Because you practiced a different epistemology, you accessed different knowledge. And you documented it with two tools working together.

Here's what we want you to understand: the camera and the notebook aren't separate. They're not "writing versus photography" or "observation versus documentation." They're integrated tools in your ethnographic practice. The notebook captures what you think and observe and notice over time. The camera captures what you'd forget—the exact spatial arrangement, the material details, the visual evidence of patterns you're tracking. Together they create documentation that neither could produce alone.

This gives you something concrete to do with your camera that actually matters. Not Instagram content, not aesthetic experimentation, not "travel photography"—documentary ethnography. You're using your phone camera the way anthropologists use theirs in the field, the way photojournalists use theirs when documenting social reality, the way Baudelaire would have used one if he'd had access to the technology. You're making images that serve knowledge production rather than content circulation.

And this transforms what photography means in the context of tourism. Instead of photographing to verify you were there, you're photographing to remember what was there. Instead of capturing aesthetically pleasing moments, you're capturing analytically useful evidence. Instead of seeking the perfect shot, you're building a visual archive that supports your written observations. The camera becomes a research tool, not a performance tool.

Your notebook and your camera together produce field documentation that's singular and non-reproducible. Someone else could sit in the same cafe with their own notebook and camera, could follow the same protocol, could even observe the same populations. But they cannot reproduce your knowledge because of temporal singularity—the cafe operates differently now than during your fieldwork. Because of relational specificity—your transformation from stranger to temporary regular is uniquely situated. Because of observational contingency—what you noticed and photographed depends on what happened to occur during your specific visits.

This is the opposite of viral content, which derives value from reproducibility. Your ethnographic documentation derives value from singularity. You accessed a Seoul that only existed in that specific temporal, spatial, and relational configuration. And you documented it with words and images working together.

What SEOULACIOUS means is experiences grounded in epistemologies beyond positivism. Ethnographic observation through systematic documentation in writing and photography. Embodied practice through knowledge acquired via repetition and duration and documented in field notes and images. Temporal depth through patterns visible only across multiple visits and captured through comparative photography. Relational integration through transformation from stranger to temporary regular, tracked in writing and illustrated with evidence. Intellectual legitimacy because you're doing what Baudelaire did, what anthropologists do, what documentary photographers do.

What SEOULACIOUS also means is the quiet radicalism of analog methods in digital Seoul. The pleasure of hand-writing observations in a locally purchased notebook from a Korean stationary shop, feeling ink marks and deep scratches on paper become evidence of reality-grounded thinking. The refusal of digital-first logic that assumes everything worth documenting must be instantly shareable. The accumulation of a physical artifact that holds not just knowledge but the embodied memory of your research process. Yes, you can supplement with video notes if helpful, but make the paper notebook central—let analog documentation be your resistance to platform optimization.

The methodology is ethnographic touring using integrated notebook and camera work. Three-hour minimum participant observation sessions with both writing and photography. Field notes documenting spatial practice and social rhythms and material culture and language interaction and embodied experience, illustrated with photographs that serve analysis rather than aesthetics. Three-day repetition at an anchor site to establish patterns visible in comparing images across time. Neighborhood radius expansion to map cultural ecology through walking and documenting. Baudelairean walks with no destination and systematic photographic documentation of what you observe. Writing it up afterward as blog post or Facebook essay with your photographs illustrating your observations.

The outcome is ethnographic data that TikTok tourists literally cannot produce. You'll know one Seoul neighborhood deeply instead of "seeing" fifty neighborhoods superficially. You'll understand how Korean cultural practices operate through mechanisms that quick Instagram photos cannot capture. You'll have field notes and photographic documentation containing knowledge that's non-reproducible because it's uniquely situated, non-algorithmic because it's invisible to search, embodied and tacit and visual in ways that resist quick categorization, and non-commercial because it's not optimized for content.

This is research-grade cultural knowledge. And you produced it yourself with nothing more than a notebook, a camera, and the willingness to sit still long enough to pay attention while documenting what you see.

The reproduction machine will keep running. Lists will keep generating. Tourists will keep photographing signature items from prescribed angles, creating content that looks like everyone else's content. That's fine—they're practicing a valid epistemology for their purposes.

But there's another Seoul, ethnographically rich and temporally complex and embodied and tacit and illegible, waiting for those willing to practice a different epistemology. A Seoul that reveals itself not in fifteen minutes but across three days. A Seoul that exists not in Instagram posts but in field notes and documentary photographs working together. A Seoul that transmits not through verification but through duration and systematic observation.

And here's what we promise you: six months from now, a year from now, these slow observations will be what you remember most vividly. Not the stack-and-pack verification tourism, but the morning regular who took the same table three days running. Not the viral dessert you photographed, but how your body felt different on Day 3 when the barista made your order before you finished requesting it. Not the aesthetically pleasing moments, but the patterns you discovered through sustained attention. The slow experiences teach you the most about place and space, and they become the most memorable precisely because they were situationally specific rather than globally reproducible.

That's the SEOULACIOUS Seoul. Now go be an urban ethnographer. Be Baudelaire in Bukchon. The notebook and camera are waiting, and they work best together.

For advanced ethnographic methodology training including photo-sartorial elicitation techniques and urban interface mapping protocols, see KARSI's Seoul Space Lab programs at karsi.org

Further reading: Charles Baudelaire, "The Painter of Modern Life" (1863); Walter Benjamin, "The Flâneur" from The Arcades Project; Michel de Certeau, "Walking in the City" from The Practice of Everyday Life; and our own work documenting seventeen years of systematic Seoul observation at seoulacious.com