Under Korea's Glass Skin: The Truth in Grit and the Grip of Grime

PSY knew it. Korean Instagram knows it. Even Bong Joon-ho proved it. So why does everyone keep pretending Korea's appeal lives in the polish?

The scene: Le Chamber, a Cheongdam-dong speakeasy where a single cocktail costs ₩27,000 (about $20) plus a ₩10,000 cover charge, and every surface gleams like it's been surgically enhanced. The bartender has glass skin—literally, the K-beauty ideal of pore-less, light-reflecting perfection. The interior is all white marble and brass fixtures. To enter, you press a specific book on a shelf like you're unlocking a secret passage. Your reflection in the mirror looks like it's been passed through three Instagram filters before it even hits your retina. Everything is so polished you could slip and crack your skull on the aesthetic.

This is the Korea the world sees. K-pop idols with 10-step skincare routines and not a hair out of place. Gangnam towers reflecting sunlight off their glass facades. BTS members whose faces have been optimized to the point of uncanny valley perfection. It's beautiful. It's impressive. But it's not the whole story of what makes Korean culture actually compelling.

Here's what nobody wants to admit: Korea's glass skin is precisely what makes it hard to hold onto. Surfaces that polished offer nothing to grip. You slide right off them, impressed but unchanged, entertained but not engaged. The Korea that actually sticks—the one that gets under your skin and makes you want to understand it at a deeper level—isn't shiny at all. It's grimy, decadent, rough around the edges, and nobody's exporting it because it doesn't photograph well for soft power campaigns.

PSY understood this in 2012 when he made "Gangnam Style." He spent the entire video mocking Gangnam's glass skin aesthetic—the polished perfection, the performed wealth, the obsession with surfaces. He opened by lounging under an umbrella on what looks like a luxury beach, then pulled back to reveal a children's sandbox. He partied in what seemed like exclusive venues, then revealed they were parking garages and public bathhouses. His whole thesis was that Gangnam's shiny surface was hollow, pathetic even. As he confessed in a behind-the-scenes moment of radical honesty: "Human society is so hollow, and even while filming I felt pathetic. Each frame by frame was hollow."

Three billion people watched that video. Almost none of them understood they were watching Korea's most successful cultural export mock the very thing Korea exports: polished, perfect, hollow beauty.

The grime underneath has a name: twepemi

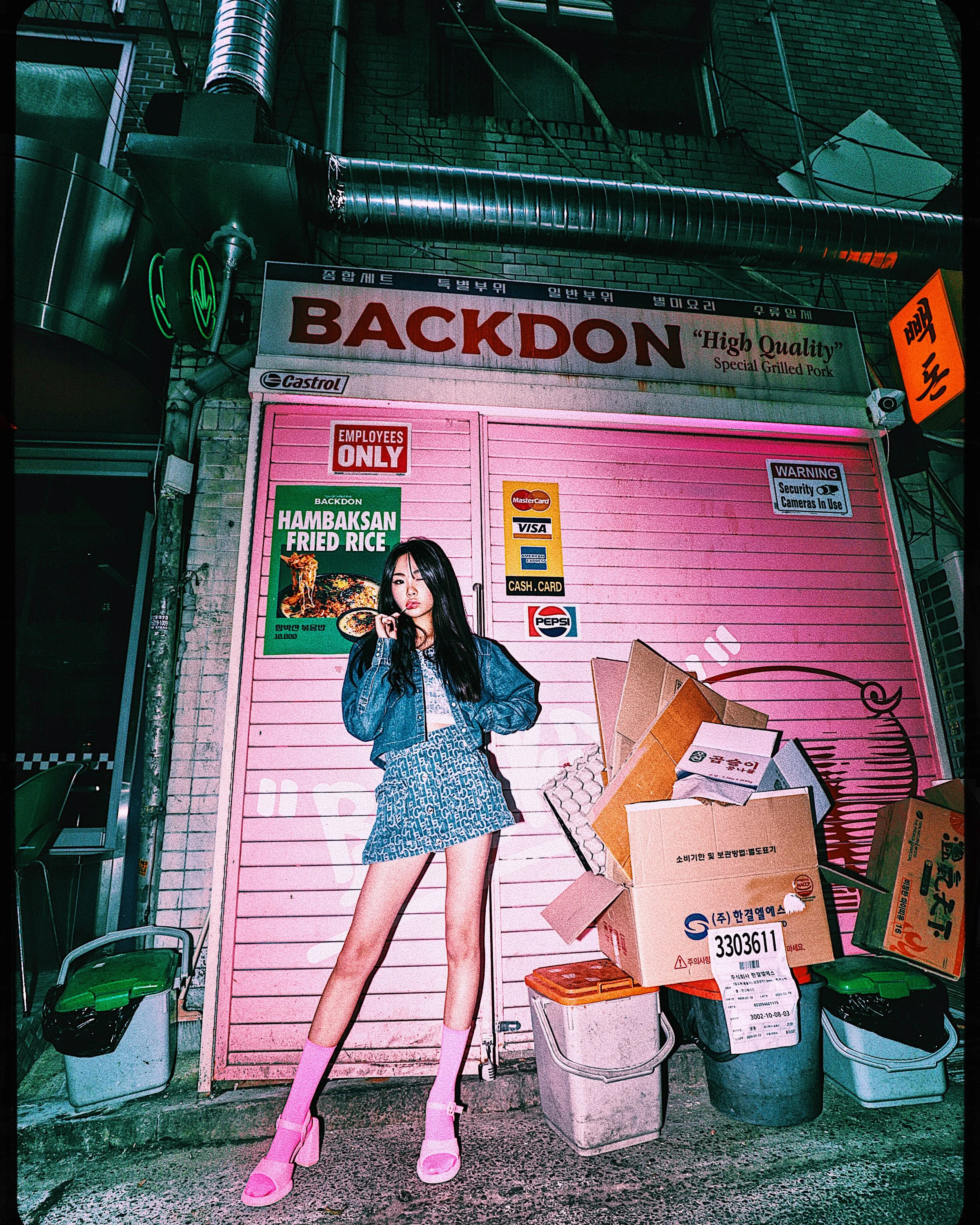

Model @sio.0.show at Seoul Fashion Week in September 2025.

Korean has a word for the beauty found in decay, exhaustion, and moral transgression: toepemi (퇴폐미, pronounced "TWAY-peh-mee"). It combines toepe (decadence, corruption, the departing from social norms) with mi (beauty). This isn't some cutesy aesthetic trend. This is a philosophical position encoded in Sino-Korean that celebrates hollow eyes, smudged makeup, disheveled hair, all-black clothing, and the specific allure of looking like something has happened to you.

Being called toepejok (decadent) is an insult. Having toepemi (decadent beauty) is a compliment. The distinction matters. You're not attractive despite looking wrecked—you're attractive precisely because you look wrecked. The aesthetic encodes experience, trauma even, as visual appeal. This is Korean compressed modernity processing itself through appearance: the violent rush from poverty to prosperity in two generations left marks, and those marks became desirable.

Walk through Seoul's Instagram geography and you'll see toepemi everywhere. The hashtag #퇴폐미 marks moody photography with film grain, exhausted models with dark circles they didn't conceal, neon-lit back alleys at 3 AM, cafés that look like they're decaying from the inside out. These aren't accidents or failures of maintenance. This is deliberate aesthetic labor—the conscious cultivation of imperfection as the only honest response to hyperdevelopment.

This isn't Western grunge imported. This is indigenous Korean aesthetic philosophy processing what sociologist Chang Kyung-Sup calls "compressed modernity"—centuries of development condensed into decades, traditional neighborhoods razed overnight, the psychic whiplash of becoming a global economic power before your grandmother died. The grime is the receipt. The decay is the evidence. And unlike K-pop's manufactured perfection, it's something you can actually hold onto.

“The grime is the receipt.“ Model @ynana5663 proves this at the Onion Cafe in Seongsu-dong.

Korea already had a framework for this: jolbakmi

Before toepemi became an Instagram hashtag, Korea possessed sophisticated philosophical frameworks for appreciating imperfection. Jolbakmi (졸박미, 拙樸美, pronounced "JOHL-bahng-mee")—literally "clumsy-rough beauty"—runs through traditional Korean aesthetics with the force of conviction. The great Joseon calligrapher Chusa Kim Jeong-hui articulated the principle as bulgye gongjol (불계공졸): "not calculating skill or clumsiness." True mastery transcends the distinction entirely.

This philosophy materialized most purely in buncheong ware, the Joseon-era ceramics that represent everything Gangnam's glass skin isn't. Where Chinese imperial porcelain demanded technical perfection and Korean royal celadon required flawless glazes, buncheong celebrated spontaneous brush strokes, uneven surfaces, and the "dipping technique" that captured beautiful accidents in fired clay. Korean art historians describe it as possessing "a folk sentiment that is unwitting yet subtly natural"—musimhamyeonseo-do eungeunhan jayeonmi (무심하면서도 은근한 자연미). Excellence that doesn't announce itself. Beauty that looks artless.

The philosophical foundation comes from the Taoist principle daegyo yakjol (대교약졸): "great skill appears clumsy." This inverts conventional aesthetics entirely. True mastery hides itself. Perfection that shows its work is suspect. The hanok that's beautiful because every element serves function, not decoration. The calligraphy that transcends calculated technique. The pottery that captures spontaneity in permanent form.

Contemporary Seoul channels this whether it knows it or not. When developers transformed Seongsu-dong's abandoned shoe factories into cafés, they kept the rusty metal, the industrial grime, the traces of previous occupants—not despite these imperfections but because of them. Café Onion's grey concrete walls aren't minimalist design choices; they're the actual 1970s factory bones, preserved because rough beats polished every single time.

The philosophical gap: Korean grime vs Japanese wabi-sabi

Japanese wabi-sabi offers the obvious comparison—both aesthetics valorize imperfection—but the comparison reveals more difference than similarity. Wabi-sabi operates through serene acceptance. Korean grime aesthetics operate through tension. This distinction is philosophically fundamental.

Wabi-sabi, rooted in Zen Buddhism and refined through centuries of tea ceremony, invites practitioners to find peace in transience. The tea master Sen no Rikyū introduced deliberately humble ceramics and tiny tea houses to strip away ego and status. The emotional response wabi-sabi cultivates is quiet melancholy, gentle surrender to impermanence. As aesthetic philosopher Andrew Juniper describes it: "a sense of serene melancholy and spiritual longing."

Toepemi carries no such serenity. It is sensual where wabi-sabi is ascetic, rebellious where wabi-sabi is accepting, backward-looking where wabi-sabi emphasizes present-moment awareness. Korean grime aesthetics encode trauma—the "take-no-prisoners, often violent modernization" that razed neighborhoods within a generation. The nostalgia in toepemi is for things never had, experienced by young people who never knew life without WiFi but who pine for "the greener grass of the slower, easier, cooler time immediately prior."

This explains a curious asymmetry: wabi-sabi became globally famous through books and design trends while Korean equivalents remain obscure even to Korea enthusiasts. Japan had centuries to refine and export its aesthetic philosophy. Korea's compressed development left less time for crystallization. More importantly, Korea exports K-pop perfection, not philosophical frameworks of imperfection—a brand strategy that obscures the grime that actually makes Korean culture sticky.

Wabi-sabi says: accept the crack in the bowl, it makes it more beautiful. Toepemi says: the crack is where the trauma shows through, and that's why you can't look away. One is zen. The other is a wound still healing.

Why “Cool Japan” failed: The catch mechanism explained

Cool Japan arrived with impeccable credentials. Government-backed soft power campaigns, UNESCO-recognized aesthetics, centuries of refined cultural philosophy. Wabi-sabi became a global design trend. Minimalism conquered Western interiors. Japanese efficiency and technological sophistication became aspirational worldwide. And yet Cool Japan never stuck the way the Korean Wave has.

The problem wasn't quality - it was friction. Or rather, the absence of it.

Cool Japan was curated perfection: bullet trains that run on atomic-clock precision, high-tech toilets with more features than your phone, ryokan minimalism so refined it felt like a museum. Even when Japan exported its appreciation for imperfection through wabi-sabi, it arrived polished - coffee table books explaining the beauty of aged ceramics, design magazines showing perfectly composed shots of weathered wood. The imperfection itself was perfected.

There was nothing to catch on. Nothing relatable. Nothing messy enough to grab onto.

The problem with even showing off the Tokyo “street” was that while it was kinda “real” it presented Japan as curio, as weird and colorful Other, and the better it was to gawk at, the less most western (or likely even average Japanese people ) could relate to it. These fashion subculture kids were just there to point and titter at — they didn’t really tell you anything about Japan or the subcultural angst that produced the subjects you were looking at.

The catch mechanism requires friction at the point of contact. This is where the physics metaphor becomes literal cognitive science. When culture presents as flawless - whether it's Cool Japan's zen minimalism or Korea's glass-skin K-pop - your brain processes it quickly, categorizes it as "beautiful but foreign," and moves on. Admiration without adhesion. You slide right off the polished surface.

But when culture shows its grit - the exhaustion in toepemi aesthetics, the rough edges of jolbakmi pottery, the decaying Euljiro workshops, PSY mocking Gangnam's hollow perfection - your brain slows down. The imperfection creates cognitive friction. You can't quickly categorize it. Is this aspirational or cautionary? Beautiful or disturbing? The ambiguity forces engagement. The rough texture provides something to actually grasp.

More importantly, grime is universal. Everyone knows exhaustion. Everyone has felt hollow. Everyone understands the gap between performed perfection and messy reality. When Korean culture shows its toepemi - its decadent beauty born from compressed modernity's trauma - international audiences don't just admire it from a distance. They recognize it. They relate to it. The grime creates entry points for emotional connection in a way that pristine beauty never can.

This is why Squid Game became a global phenomenon. Not despite its grime but because of it. Debt-ridden players in cheap tracksuits, desperate enough to risk death playing children's games - this wasn't aspirational Korea. This was the underbelly, the people crushed by Korea's economic miracle rather than elevated by it. And global audiences, drowning in their own student debt and wage stagnation, caught onto that immediately. The grime was the point of connection.

Cool Japan said: "Look at our refined aesthetics, our ancient wisdom, our technological perfection." It was impressive. It was also alienating. There was no place for the viewer to enter, no shared experience to connect through, no friction to create the catch.

Korea - accidentally, through toepemi Instagram aesthetics and newtro nostalgia and PSY's satirical honesty - is saying something different: "Look at how fucked up and exhausted and hollow this rapid modernization made us. Look at the grime under the glass skin." And global audiences, especially young people navigating their own exhausted relationship with performed perfection on social media, catch onto that immediately.

The catch happens in the friction. And friction requires texture, imperfection, grit. Cool Japan was too polished to create friction. Korea's grime - whether intentionally or accidentally - creates exactly the textured surface where cultural catch can occur.

This is why the same Korean influencers who maintain glass-skin perfection for their selfies seek out gritty Euljiro bars for their content. They intuitively understand you need both registers. The polish gets attention. The grime creates the catch. Cool Japan only had the polish. Korea - beneath its glass skin - has the grime that actually makes culture stick.

Euljiro's economics: How grime became the product

Nowhere does this tension manifest more clearly than in Euljiro 3-ga, Seoul's industrial neighborhood now nicknamed "Hipjiro" (힙지로, a portmanteau of "hip" + "Euljiro"). Here's the paradox that proves the thesis: commercial rents rise precisely because the surrounding aesthetics are "way down in the proverbial dumps." The grime is the attraction. The decay is the amenity.

Euljiro's original identity—oil-stained metal workshops, grumpy ajussis (아저씨, middle-aged/older men) drinking cheap beer after work, decades of industrial grit—has become set design for moody bars that evoke Wong Kar-wai films. The aesthetic is "found object" mise-en-scène: mismatched vintage furniture, exposed concrete, minimal signage, deliberately forbidding entryways. One bar features wobbly chairs and tchotchkes that feel "defiantly unpretty in contrast to the clean Instagram-friendly lines that are the current 'it' aesthetic."

The visual sociology here is precise. Young Koreans—and international visitors—find these spaces more compelling than Gangnam's glass towers because texture creates cognitive engagement. Neuroscience research confirms that asymmetry and imperfection capture attention more deeply than flawless symmetry, prompting what researchers call "prolonged and contemplative cognitive experience." Polished surfaces slide past. Rough textures demand examination.

Korea's newtro (뉴트로) phenomenon—the "new retro" movement that emerged around 2018—crystallizes this dynamic. Unlike simple nostalgia, newtro reinterprets 1980s-90s aesthetics through contemporary sensibilities, targeting ages 10-30 who never experienced those decades firsthand but crave their visual texture. The Reply K-drama series triggered the retro boom. Gudak Cam, a Korean app that simulates disposable cameras requiring three days for photos to "develop," made analog inconvenience fashionable.

This is aesthetic arbitrage. Gangnam represents the future Korea wants to project—high-tech, wealthy, flawless. Euljiro represents the past Korea razed to get there—industrial, working-class, imperfect. And the market has decided the past is more valuable as cultural product than the future. The grime appreciated faster than the glass.

RIsing star and teen model @parkjiyoon100823 brings kidsy cute to this back alley spot in the Euljironeighborhood of Seoul.

Why tourists find "wrong Seoul" more compelling

Travel writing about Seoul reveals a consistent pattern. First-time visitors hit Myeongdong or Gangnam, dutifully photograph the Lotte Tower, buy sheet masks in bulk. Those who return gravitate toward Ikseon-dong, Euljiro, Seongsu-dong—the neighborhoods with texture. As one Seoul guide confesses: "The night I discovered Euljiro's retro bar alleys by accident, I realized I'd been staying in the wrong Seoul entirely."

The logic transcends individual taste. Gangnam offers modernity that could exist anywhere—sleek towers, branded luxury, international chains. Paris has it. Dubai has it. Singapore has it better. Euljiro offers modernity that could only exist here: the specific layering of Korean industrial history, the particular way neon reflects on rain-slicked pavement beside 60-year-old machine shops still operating. The grime is site-specific. The polish is generic.

Ikseon-dong exemplifies this appeal. Built in the 1920s for working and middle-class tenants, its hanoks lack Bukchon's aristocratic grandeur but offer something more valuable: texture of actual life. Original residents still live among converted cafés. Old women sell vegetables next to specialty coffee roasters. The space functions as living neighborhood, not heritage museum. Travel writers recommend it when "foreign friends want 'traditional Korea' without tourist chaos."

Bong Joon-ho understood this aesthetic calculus in Parasite. The banjiha semi-basement apartment embodies Korean grime as class marker—fumigation smoke seeping through windows, visible urination outside, the "weird mixture of hope and fear" of being half-underground. The Park family's modernist house, by contrast, is unnerving in its perfection—beautiful but uncanny, too polished to feel real. The film's visual thesis: grime reveals truth while polish conceals it.

The friction argument: Why imperfection creates grip

The neuroscience here matters. Human brains process symmetry quickly—pattern recognition evolved to identify threats and opportunities efficiently. But perfect symmetry triggers faster processing, which paradoxically means less cognitive engagement. We glance at it, categorize it, move on. Asymmetry forces slower processing, extended attention, deeper encoding into memory.

This applies directly to cultural engagement. Korea's glass skin aesthetic—K-pop's synchronized perfection, K-beauty's flawless faces, Gangnam's optimized everything—processes quickly. Impressive, certainly. But frictionless. You slide right off the surface, entertained but not transformed.

Compare this to encountering toepemi. You're looking at Instagram photos tagged #감성사진 (gamseong sajin, "emotional/atmospheric photography"): film grain, muted colors, a person with hollow eyes in a decaying café at 2 AM. Your brain can't process this quickly. Is this beautiful or disturbing? Aspirational or cautionary? The ambiguity forces engagement. The texture provides grip.

This is why the same Korean influencers who maintain 10-step skincare routines for glass-skin selfies simultaneously seek out gritty Euljiro bars for content. They understand intuitively what the neuroscience confirms: you need both registers. Polish for the approach, grime for the grip. The glass skin gets attention. The rough texture gets remembered.

The hashtag ecosystems reveal this dual operation:

#퇴폐미 (toepemi) marks decay aesthetics explicitly

#뉴트로 (newtro) signals newtro reinterpretation

#힙지로 (Hipjiro) claims Euljiro's industrial cachet

#감성사진 (gamseong sajin) denotes moody atmospheric photography

#필름카메라 (pilleum kamera) celebrates film grain and light leaks

The influencer posts polished personal photos—K-beauty standard selfies, well-lit OOTDs (outfit of the day posts)—alongside gritty location shots emphasizing imperfection. The contrast itself becomes content strategy, demonstrating cultural range. Personal appearance gets the glass skin treatment. Environmental aesthetics get the grime.

Cultural capital and the class politics of appreciating roughness

Pierre Bourdieu's insight applies directly: "Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier." The appreciation of toepemi (퇴폐미) and newtro aesthetics functions as cultural gatekeeping. Navigating Euljiro's hidden bars, distinguishing authentic vintage from kitsch, reading decay as desirable—these require cultural capital that education and cosmopolitan exposure provide.

The irony shouldn't be ignored. The young entrepreneurs opening cafés in old Euljiro buildings are often well-educated, cosmopolitan individuals engaging in aesthetic slumming. They appreciate roughness precisely because they possess the security to find it charming rather than threatening. Anti-gentrification movements march through Euljiro accusing these same artists of causing displacement while claiming to resist it.

This class dimension complicates but doesn't invalidate the aesthetic argument. The preference for imperfection remains genuine even when its sociological function is distinction-making. The ability to appreciate grime has always been a luxury—the poor who must live with decay rarely romanticize it. What Korean newtro culture offers is democratized access to this appreciation, packaging working-class aesthetics for middle-class consumption.

But here's what matters for anyone trying to actually understand Korean culture at depth: the grime is real even when the appreciation is performed. PSY wasn't wrong when he called Gangnam society hollow. The compressed modernity trauma encoded in toepemi aesthetics isn't manufactured nostalgia. The jolbakmi philosophy predates Instagram by centuries. The fact that these aesthetics now function as cultural capital doesn't make them less authentic—it makes them more important to understand.

What this means for anyone trying to grasp Korea

If you want to slide off Korea, stay on the glass skin surface. Consume K-pop, admire K-beauty, visit Gangnam, take your Instagram photos at the polished cafés in Gangnam or Cheongdam-dong. You'll have a perfectly pleasant time. You'll see the Korea that Korea wants you to see—the soft power projection, the economic miracle, the manufactured cool.

If you want to actually get a handle on Korean culture—to wrap your hands around something textured enough to hold onto—you need the grime. You need to understand why toepemi emerged as indigenous aesthetic response to compressed modernity. You need to see how jolbakmi has operated in Korean material culture for centuries. You need to recognize that PSY's "Gangnam Style" was never a celebration—it was a diagnosis, and the patient is still sick.

The Korea that makes K-pop idols maintain impossible beauty standards while simultaneously creating Instagram aesthetics that celebrate exhaustion and decay is processing profound cultural contradictions. The tension between these registers isn't a bug, it's the feature. The productive friction between shiny and grimy Korea is precisely what gives Korean culture its intellectual and emotional resonance.

Anyone trying to understand Korean culture beyond surface-level content needs to see this: Korea's most compelling cultural production isn't the polish it exports but the texture it creates to survive the polishing process. The grime isn't what Korea overcame to become modern. The grime is modernization's receipt, the proof of transformation, the scar tissue that makes the body interesting.

Glass skin is beautiful, yes. But you can't hold onto it. Your fingers slip right off. It's the rough patches—the toepemi cafés, the jolbakmi pottery, the newtro decay, the Euljiro grit, the banjiha basements, the honest exhaustion underneath the performed perfection—that give you something to actually grasp.

PSY knew this when he filmed himself in that children's playground pretending it was a beach. Bong Joon-ho knew this when he put his camera in the semi-basement. Korean Instagram knows this every time it applies a film grain filter to a photo of someone who looks like they haven't slept in days.

The only people who don't seem to know it are the ones still trying to convince you that Korea's appeal lives in the shine.