Who Owns the Teenage Girl? Inside Korea's School Uniform Wars

Model @sio_0_show takes the leap to freedom from school grounds in the Anguk-dong/Buchon area on a cold November night.

When K-pop groups started suing each other over who invented "schoolgirl aesthetic," it revealed how thoroughly uniforms became contested cultural capital—and what that means for actual teenage girls.

June 2024. In a Seoul courtroom, lawyers for HYBE Labels and ADOR are arguing over intellectual property rights. The contested property isn't a song or a logo or a dance move, though those are involved too. The core dispute centers on something more fundamental: who owns the aesthetic of being a teenage girl in school clothes.

On one side: NewJeans, the group that debuted in July 2022 with a carefully curated "dreamy school uniform concept"—Y2K-inspired styling, casual confidence, the specific energy of girls between childhood and adulthood captured in pleated skirts and cardigans. On the other: ILLIT, who debuted in March 2024 under HYBE's subsidiary Belift Lab with what NewJeans' supporters claim is suspiciously similar aesthetic DNA. The lawsuit alleges wholesale concept theft: the uniforms, yes, but also the choreography, the visual mood, the entire performed identity of youthful femininity.

The legal filings run hundreds of pages. Exhibit A includes Instagram posts, music video timestamps, styling breakdowns. Expert witnesses discuss the semiotics of collar styles and sock lengths. Lawyers argue over whether you can copyright a vibe. The stakes are enormous—billions of won in projected revenue, control over lucrative brand partnerships, dominance in the most competitive pop music market on earth.

But step back from the legal maneuvering and a stranger question emerges: how did we get to a place where major corporations sue each other over who owns the look of being a student? School uniforms were designed to eliminate individual distinction, to enforce conformity, to make everyone look the same. They're institutional garments, instruments of control, material manifestations of "forgetting your individual self and merging with collective consciousness," as one anthropologist put it.

So what happened? How did these symbols of conformity become valuable enough to fight over in court? How did the clothes meant to erase difference transform into contested intellectual property worth millions?

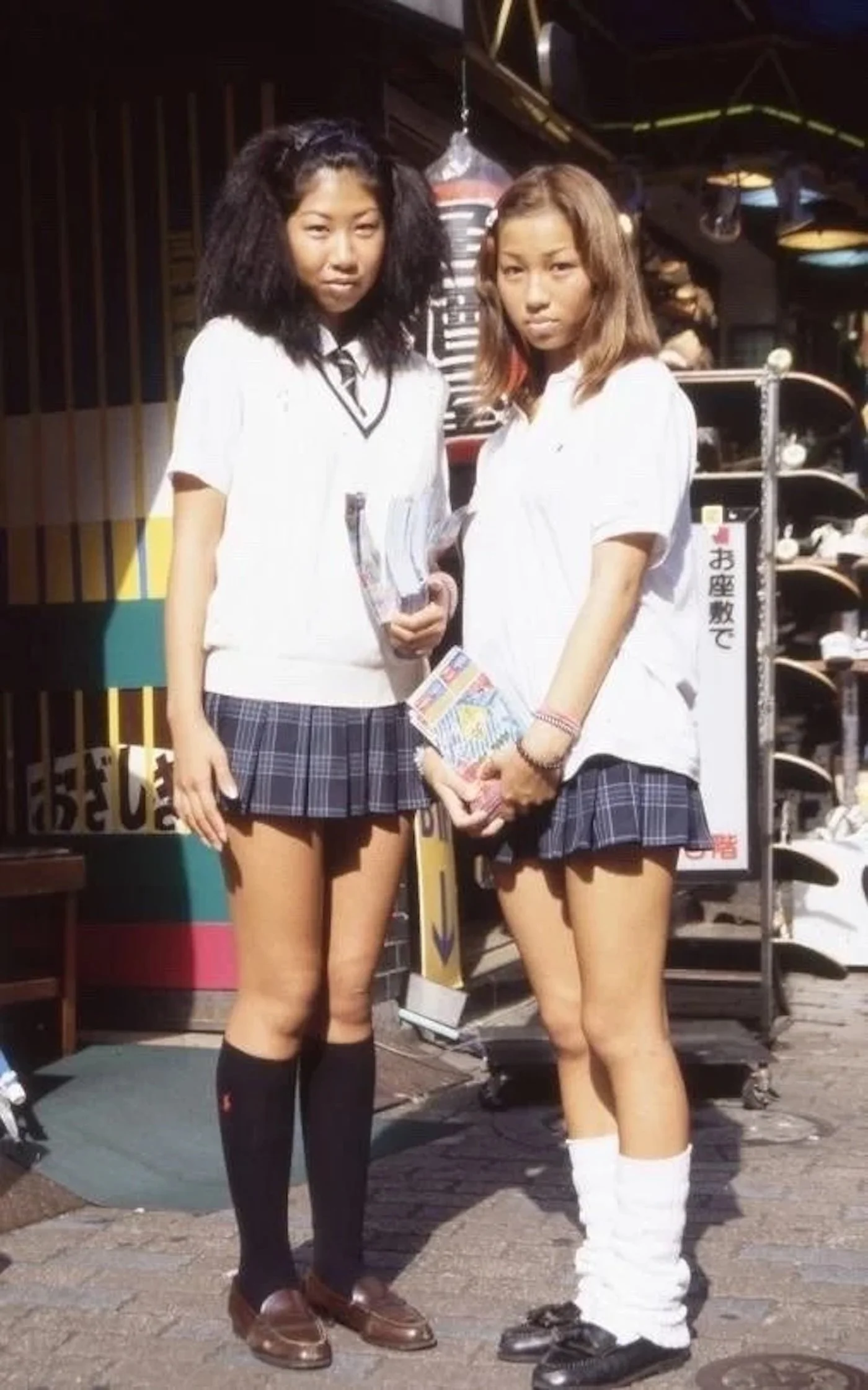

This isn't actually a story about NewJeans and ILLIT. This is a story about what happens when institutional control creates the conditions for its own commodification. And to understand how we got here—to this bizarre moment when entertainment companies litigate over schoolgirl aesthetics—we need to go back twenty-five years, to Tokyo's Shibuya district in 1993, where something shifted.

THE SHIBUYA REBELLION

The Japanese school uniform—specifically the sailor-style seifuku that became iconic—has military origins. In 1921, a British English teacher named Elizabeth Lee introduced the design at Fukuoka Jo Gakuin, modeling it after Royal Navy attire she'd encountered as an exchange student in England. The style spread rapidly across Japan for practical reasons: straight collar lines matched existing Japanese dressmaking techniques, and the design represented Western-style modernity while allowing greater freedom of movement than kimono.

But the deeper appeal was ideological. This was Meiji-era Japan, racing to modernize, desperate to signal civilizational progress to Western powers. School uniforms became what scholar Brian McVeigh calls "material markers of a life cycle managed by powerful politico-economic institutions." They announced: we are modern, we are disciplined, we can produce citizens as orderly and productive as any Western nation. Students wearing these uniforms were meant to embody the national project, to subsume individual identity into collective purpose.

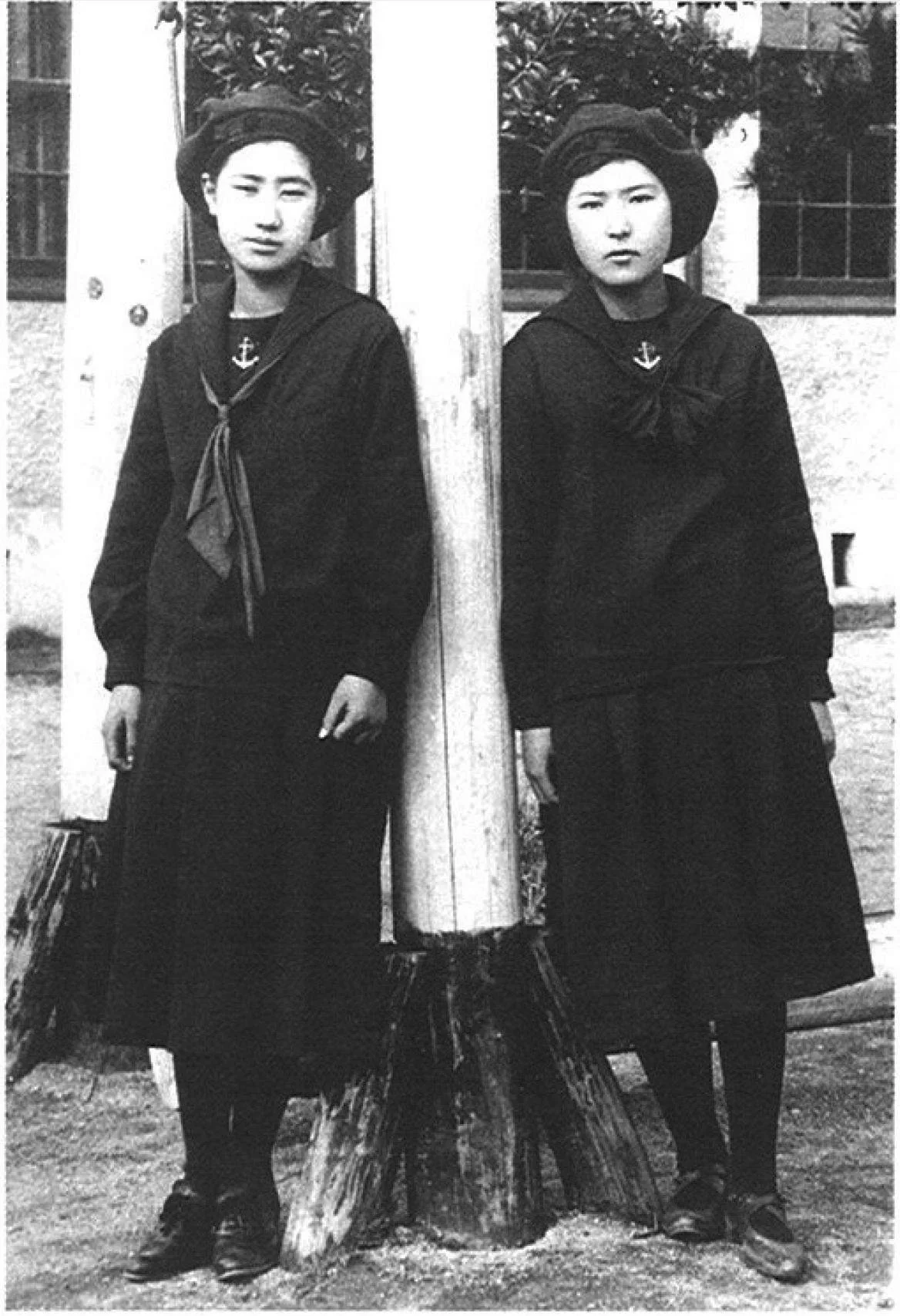

“Students of Fukuoka Jogakkou 1920's Fukuoka Japan.” [Image SOURCE]

For decades, this function remained stable. Students wore uniforms. Schools enforced strict compliance. The sailor suit meant what it was designed to mean: you are a student, you are controlled, you are the same as everyone else.

Then, between 1991 and 1993, among a specific cohort of girls attending elite private schools in Tokyo's Shibuya district, something unexpected happened.

The kogal (コギャル) phenomenon didn't emerge from nowhere. Scholar Namba Koji traces its origins to four converging late-1980s trends. First, the bodikon disco era had introduced "gal" culture—young women in body-conscious dresses, tanned skin, bleached hair, appropriating Black American and Latina aesthetics into Japanese contexts. Second, Shibuya was exploding as a nightlife center after the DC fashion boom collapsed in 1988, creating dense networks of clubs and gathering spaces. Third, elite students were organizing underground dance parties—the chiimaa (teamers), named after their self-organized "teams," who developed sophisticated subcultural identities around music and fashion.

But the crucial fourth factor was the School Identity movement of 1987. For the first time, designer uniforms at wealthy private schools made students proud to wear their uniforms publicly, rather than hiding them or changing immediately after school. The uniform shifted from stigma to status symbol—but only at specific schools, creating new hierarchies of institutional prestige made visible through clothing.

Kogals seized this opening and ran with it. The modifications followed specific codes: skirts shortened to extreme mini-length by rolling the waistband, loose socks (ruuzu sokkusu) bunched dramatically at the ankles, hair bleached to brown (chapatsu), artificial tanning, heavy makeup emulating pop singer Namie Amuro. Each element carried meaning within the subculture—the deeper the tan, the higher the status; the looser the socks, the more committed to the aesthetic.

This wasn't sexual availability, despite how it would later be interpreted. Linguist Laura Miller documented how kogals "challenged dominant models of gendered language and behavior through linguistic and cultural innovation." They created female-centered subcultural identities through slang and style. The shortened skirts weren't invitations—they were fashion statements, assertions of autonomy, visible markers of belonging to a peer group that mattered more than institutional authority.

The theoretical framework for understanding this transformation comes from cultural theorist Dick Hebdige's concept of bricolage—the way subcultures "cobble together" styles from available cultural materials to construct identities that confer relative autonomy from dominant culture. Kogals were practicing bricolage with the rawest, most universally accessible material imaginable: the clothes they were already required to wear.

That's the uniform's peculiar power. Unlike other subcultural styles that require purchasing specific items—punk's leather jackets, hip-hop's sneakers, goth's elaborate makeup—uniform modification requires no additional resources. Every student already possesses the raw material for rebellion. And crucially, modifications can be reversed before inspection, creating what Miller identifies as "subtle rebellion against strict dress codes without overt rule-breaking." Roll the waistband up during the day, roll it down for the train ride home past your parents. Pull the socks up walking to school, bunch them down in Shibuya. The garment designed to eliminate individual distinction becomes, through accumulated tiny modifications, the most visible site for asserting it.

In 1995, Egg magazine launched, dedicating itself to documenting kogal street fashion. What had been a localized Shibuya phenomenon exploded nationally. The magazine didn't just report on kogals—it transformed them into a legible, imitable aesthetic category. Scholar Sharon Kinsella describes the girls as engaging in "camp and self-conscious delight in being photographed," aware they were performing for media consumption. This awareness didn't diminish authenticity; it transformed the relationship between youth practice and commercial exploitation into a feedback loop. Girls modified uniforms to express identity, magazines documented those modifications, other girls copied what they saw in magazines, creating new modifications to distinguish themselves, which magazines then documented, and round and round.

(Two years later, Shoichi Aoki would launch FRUiTS magazine, documenting broader Harajuku street fashion including gothic lolita, visual kei, and decora alongside uniform-based styles. While Egg remained kogal-specific and domestically focused, FRUiTS became the primary lens through which international audiences understood Japanese youth style innovation—meaning most Western readers encountered Japanese school uniform aesthetics through FRUiTS's eclectic street fashion documentation rather than Egg's kogal-specific coverage.)

By 1996, kogal slang dominated Japan's annual Ryukogo Taisho awards for trendy words. Television specials like Za kogyaru naito introduced the aesthetic to mass audiences. Media coverage exploded. This was peak cultural influence—but it was also the beginning of what Hebdige calls recuperation: the commercial and ideological incorporation of the subversive into mainstream acceptability.

Uniform manufacturers began designing skirts that were easier to shorten. Magazines that had documented rebellion became instruction manuals for conforming to new norms. What started as transgression calcified into a different kind of uniformity—you had to modify your uniform in the right ways or you weren't really kogal at all. The rebellion became a product line.

But there was a darker recuperation happening simultaneously.

THE ADULT APPROPRIATION

While teenage girls were modifying uniforms as expressions of autonomy, fashion identity, and subcultural belonging, adult men were watching. And adult industries were taking notes.

The burusera (ブルセラ) phenomenon—shops selling used school uniforms, particularly underwear—emerged during the kogal era. The term combines "bloomers" and "sailor suit," making explicit what was implicit: the adult male sexual fetishization of school uniform imagery. Stores in Tokyo's red-light districts offered used uniforms at premium prices, marketed explicitly for their association with teenage girls. Adult video production adopted seifuku imagery as a dominant genre. Maid cafes proliferated, their costumes riffing on school uniform aesthetics. An entire commercial ecosystem developed around the sexualized schoolgirl image.

The feedback loop grew poisonous. Media coverage began linking kogal fashion to enjo kōsai (援助交際)—"compensated dating," a euphemism for teenage girls meeting older men for money. Medical researcher Akaeda Tsuneo pushed back hard against this conflation: "the girls called gyaru had too much pride and weren't the ones doing enjo kōsai." But the media narrative persisted, collapsing the distinction between youth fashion and sexual transaction.

Scholar Sharon Kinsella identifies the dynamic with brutal clarity: coverage often "fetishized school uniforms and blamed those required to wear them." Girls became responsible for adult desire directed at their institutional clothing. The very garment meant to desexualize and control teenage bodies—to render them uniform, identical, unseeing and unseen—became the object of intense sexual scrutiny precisely because it was supposed to signify innocence and institutional protection.

The contrast with earlier sukeban (スケバン) delinquent culture is instructive. In the 1970s-1980s, girl gangs modified uniforms in the opposite direction—lengthening skirts to ankle-length, explicitly rejecting sexualization as feminist protest against the sexual revolution's objectification of women. Sukeban wore long skirts as armor, as refusal, as visible rejection of male gaze. Their uniform modifications said: we will not be available to you, we will not be cute for you, we will take up space and wield violence if necessary.

Kogal shortened skirts weren't embracing sexualization—they were asserting style and youth identity in the specific subcultural context of 1990s Shibuya. But adult interpretation collapsed this crucial distinction. The media, the adult entertainment industry, the moral panic machinery—all insisted that shortened skirts meant sexual availability, regardless of what the girls wearing them said they meant.

Kinsella documents the "extraordinarily close interaction" between kogal culture and "male journalistic and subcultural forms organized predominantly around the fetishistic portrayal of young girls." The girls were creating fashion; adult industries were creating pornography. The girls were negotiating peer status; adult media was packaging their bodies for consumption. Two completely different projects, using the same raw material.

By the late 1990s, the transformation was complete. School uniforms had become, in the Japanese cultural imagination, simultaneously symbols of institutional control and objects of adult sexual desire. The kogal girls who'd started this by rolling their waistbands in Shibuya had long since moved on—graduated, entered university, joined the workforce. But the aesthetic remained, thoroughly commercialized, thoroughly sexualized, thoroughly recuperated into exactly what it had originally opposed: a system of control, just profitable now instead of merely institutional.

And fifteen years later, across the East Sea, Korea was about to run the same experiment—but faster, slicker, and from the top down instead of the bottom up.

KOREA'S CELEBRITY-INDUSTRIAL UNIFORM COMPLEX

Korea's first school uniform appeared in 1886 at Ewha Hakdang—a modified hanbok, traditional Korean dress adapted for institutional education. The first boys' uniform followed in 1898 at Paichai Hakdang, explicitly "modeled after Japanese school uniforms." By the 1930s, Japanese colonial authorities mandated Western-style uniforms to eliminate hanbok entirely, part of the broader cultural erasure project.

After Ewha Hakdang became a proper high school, this is a picture of the lower school students, taken in the 1910s. [IMAGE SOURCE]

After liberation and the Korean War, uniforms remained standard through decades of authoritarian rule. Then something surprising: in 1983, the government abolished mandatory uniforms, ostensibly to "diminish oppression and alienation while encouraging individualism." Students could wear whatever they wanted.

This lasted exactly three years. By 1986, facing complaints about class visibility and discipline problems, schools regained authority to establish uniform requirements. But when uniforms returned, they returned different. The three-year gap had allowed private uniform companies to develop branded lines marketed as fashion items rather than mere institutional requirements. Designer uniforms became competitive differentiators between schools, status symbols, consumer products.

The Big Four emerged: Elite (founded 1969, a Samsung subsidiary), Smart (1970), Ivy Club (1996), and Schoollooks. These companies didn't just manufacture uniforms—they manufactured desire. The Smart Student Model Selection Contest, running since 1996, functioned as a talent pipeline, launching careers for Song Hye-kyo, EXO's Chanyeol, and others. Being selected as a uniform model meant you were beautiful enough, aspirational enough, to embody what Korean youth should want to be.

But the real transformation came through K-pop's systematic deployment of uniform aesthetics as debut and comeback strategy. BTS debuted in June 2013 with explicitly student-directed lyrics and schoolboy styling, maintaining the aesthetic through "No More Dream," "N.O," and "Boy in Luv." EXO's "Growl" music video featured coordinated uniforms throughout, becoming iconic. TVXQ, SHINee, G-Friend—group after group used uniforms to signal youth, freshness, the specific energy of being young and not-yet-corrupted by adult concerns.

K-dramas amplified the effect: Boys Over Flowers, True Beauty, The Heirs, Hierarchy—show after show featured designer uniforms that actual students could never afford. Thom Browne blazers, Chanel-inspired pieces, Bottega Veneta styling repackaged as "school uniforms" in fictional elite academies. The shows created aspirational fantasies of school life—beautiful rich students having romantic drama in gorgeous clothes—that had nothing to do with actual Korean educational experience.

Because here's the structural difference between Japan's kogal transformation and Korea's celebrity-driven evolution: Japanese students had time to gather in physical space and develop street culture. In Japan, 92% of junior high students participate in year-round club activities (bukatsu), creating extensive after-school leisure time and dense social networks. Shibuya became the gathering point because students could gather—they had hours after school before heading home.

Korean students face radically different temporal constraints. 78.3% attend hagwons—private cram schools—averaging 7.2 hours per week, with sessions running until 10-11pm. There is no time to develop street culture. There are no Shibuya gathering spots because students are in academies, grinding through practice tests, racing toward university entrance exams that will determine their entire economic futures.

So Korean uniform culture developed through media consumption rather than physical presence. Students couldn't modify uniforms and gather in Hongdae to show them off—they were in hagwons. But they could watch music videos between study sessions. They could stream K-dramas late at night. They could follow idol Instagram accounts, absorbing the carefully curated aesthetic of youth performed by people who'd been training since middle school to embody commercial perfection.

Japan's transformation was bottom-up: street culture developed, magazines documented it, commercial forces recuperated it. Korea's was top-down: entertainment companies manufactured the aesthetic, broadcast it through dramas and music videos, and students consumed it as aspirational fantasy rather than participatory reality.

Which brings us to the most surreal manifestation of this dynamic: the uniform rental industry.

RENTING YOUTH YOU NEVER HAD

In March 2019, two Japanese tourists visit Seoul Fashion Week after having gotten real/realistic, actual Korean school uniforms from a rental shop, the goal being to experience the city as a curated insider more than an outsider. The head-to-toe styling is a perfect snapshot of the trends of the time.

It's Saturday afternoon at the Lotte World uniform rental shop, and a 28-year-old Japanese woman is selecting from the rack. She's considering the "NewJeans concept" style—₩25,000 for the day. Pleated skirt, cardigan, carefully coordinated accessories. The shop offers dozens of options: K-pop idol styles, Produce 101-inspired designs, vintage 1970s-80s aesthetics, even specific drama replicas from Boys Over Flowers or True Beauty.

She's never worn a Korean school uniform before. She's not Korean. She's renting the aesthetic of youth in a country not her own, styled after a pop group whose members are performing nostalgia for a school experience they themselves never quite had—too busy training to be idols to live normal teenage lives.

The sheer joy in embodying a whimsical notion of Korean style by this Japanese tourist is as clear as her smile is bright.

The rental shop's marketing makes explicit what's being sold: "It will remind you of your beautiful teenage memories... You'll feel like you're back in your teenagers." But whose memories? The Japanese tourist didn't attend Korean school. The 30-something Korean office worker who rents uniforms to photograph herself in Bukchon hanok village spent her actual teenage years in hagwons until midnight, not having the romantic experiences K-dramas promised. International K-drama fans renting uniforms at Everland are consuming a fiction they watched on Netflix, not recalling lived experience.

What's being purchased is the aesthetic performance of youth—the idea that being young, being a student, being in that liminal space between childhood and adulthood, looks like this: coordinated outfits, carefree confidence, romantic possibility. Never mind that actual Korean students are exhausted, stressed, competing brutally for university placement. Never mind that the performers in music videos learned choreography instead of chemistry, attended training instead of school festivals. The rental industry packages the simulacrum, and people pay ₩19,000-30,000 per day to inhabit it temporarily.

The TikTok hashtag "Korean school uniform rental" has generated 70.7 million+ posts. The content follows predictable patterns: trying on different uniforms, posing in aesthetically pleasing locations, documenting the experience of looking like a Korean student. The performance is for Instagram, for TikTok, for the followers who will validate the aesthetic success of the costume.

This is what the NewJeans lawsuit is actually about. Not uniforms as institutional garments, not uniforms as youth subcultural expression, but uniforms as commercial aesthetic property that can be rented, photographed, posted, monetized, and—crucially—legally protected. When HYBE and ADOR argue in court over who owns "dreamy school uniform concept," they're fighting over the valuable commercial right to package and sell this particular performance of youth.

The rental industry reveals how thoroughly the transformation is complete. School uniforms have become consumer products wholly detached from their institutional function. You don't need to be a student to wear one. You don't need to have attended Korean school to rent the aesthetic. You just need ₩25,000 and a desire to perform youth for your social media followers.

THE HIDDEN AGENCY: KOREAN WOMEN PERFORMING THEMSELVES

But here's where the narrative gets more complicated than simple commodification. Because alongside the rental tourism and corporate IP battles, there's another phenomenon operating: Korean women actively choosing uniform aesthetics as a form of embodied performance and self-expression.

Open Instagram and search "교복스타그램" (school uniform Instagram). You'll find thousands of posts—not rental shop marketing, not tourist documentation, but Korean women in their twenties and thirties deliberately styling themselves in uniform aesthetics for their own aesthetic projects. Accounts like @sch__uniforms gather nearly 7,000 followers documenting what they call "교복 여신" (school uniform goddesses). Major uniform manufacturers like Elite (@myelite1318) have 19,000+ followers, their feeds filled with user-generated content of women styling uniforms as contemporary fashion rather than nostalgic costume.

The top of the "“교복스타그램” hashtag on November 29, 2025.

This isn't the rental shop phenomenon. These women aren't paying to inhabit a fantasy—they're actively constructing aesthetic performances using uniform elements. The hashtag reveals a sophisticated visual culture: mixing uniform pieces with contemporary streetwear, creating "newtro" (new + retro) styling that positions school uniforms as legitimate fashion objects rather than institutional garments or nostalgic props.

My own work as a fashion photographer in Seoul confirms this pattern. I regularly receive requests from Korean Instagram models specifically asking for "school uniform concept" shoots. These aren't naive performances of celebrity aspiration—they're deliberate aesthetic choices by women who understand exactly what they're doing. They're deploying uniform aesthetics as a visual language, using the garment's cultural weight to create specific meanings in their social media presentation.

This connects to what critical dance theorist Melissa Blanco Borelli calls "hipgnosis"—the way Cuban mulata dancers used hip movement as a form of embodied agency to navigate massive social forces they couldn't control. As Borelli writes: "By choosing to perform whatever aspect of 'mulata identity' necessary for some recognition, a mulata enacting hip(g)nosis has some agency in how she is perceived. Caught within the mulata trope, she has situational agency, not projected agency."

Korean women performing uniform aesthetics operate through similar dynamics. They can't control the corporate IP battles, can't stop the rental tourism industry, can't eliminate the feminist critique of uniforms as oppressive. But they can choreograph how their bodies perform the aesthetic, choosing which aspects to emphasize, which codes to deploy, which meanings to activate. The uniform becomes what Borelli calls an "economy of visibility" where women exercise aesthetic agency through embodied performance even when they can't change the larger structures.

This reframes what we're witnessing. The uniform isn't just a passive object being fought over by corporations, tourists, and activists. It's also an active interface—a point where individual bodies meet massive social forces and negotiate meaning through performance. Korean women aren't simply being commodified; they're also using commodification as raw material for their own aesthetic projects.

The Korean term "체험형 트렌드" (experiential trend) captures this dynamic. It's not consumption or passive participation—it's active experience, embodied engagement, performance that creates meaning rather than just consuming it. When a 25-year-old Korean woman styles herself in uniform aesthetics for Instagram, she's simultaneously:

Engaging with K-pop celebrity culture she's consumed since adolescence

Negotiating feminist critiques of gender performativity

Deploying nostalgia for youth she may or may not have actually experienced

Creating visual content for social validation

Exercising aesthetic agency within constrained options

The body becomes what urban theory might call a "compressed interface"—a point where multiple temporal layers (past youth, present identity, future aspiration) and competing systems (corporate, institutional, feminist, commercial, personal) collide and produce new meanings through embodied performance.

But while Korean women are finding forms of agency through aesthetic performance, actual students are fighting the uniform's institutional function directly.

THE FEMINIST COUNTER-REVOLUTION

October 2020. Female students in Seoul Metropolitan area file formal complaints with the Office of Education. The charge: tight-fitting school uniforms constitute "sexual discrimination" and "anachronistic oppression." The uniforms restrict movement, emphasize body shape, make girls visible in ways that feel like constant surveillance. The students demand reform—the right to choose pants instead of skirts, looser cuts, practical options that don't make their bodies the primary site of institutional regulation.

The same month, Lotte World's uniform rental business hits record revenue. Weekend after weekend, tourists line up to pay for the experience of wearing the very garments actual students are protesting as instruments of gender oppression.

The contradiction is almost too perfect. Students fighting uniforms. Adults renting uniforms. Corporate lawyers litigating over uniform concepts. Feminist activists demanding uniform reform. Delinquent iljin using uniform modifications to signal power. All of these fights happening simultaneously, all centered on the same pieces of clothing.

The feminist critique has been building for years. In 2018, President Moon Jae-in ordered school uniform redesigns toward more practical options. The "free-corset" campaign, emerging from broader Korean feminist movements, targeted uniforms as symbols of how women's bodies are controlled and commodified from adolescence onward. Researcher Choi Yun-jeong at the Korean Women's Development Institute articulated the core argument: "Uniforms in Korea often exploit women, by forcing gender norms and limiting their mobility."

By June 2024, the National Human Rights Commission ruled that a Jeju school's dress code "excessively restricts students' rights to self-determination." Seoul's Metropolitan Office of Education had already implemented reforms allowing female students to choose pants. The movement was achieving concrete policy victories.

But the commercial exploitation was intensifying in parallel. In January 2023, reports emerged of elementary school uniforms exceeding ₩1,000,000—luxury branded items for children barely in grade school. K-pop groups continued deploying uniform concepts: NewJeans wore coordinated uniforms for their Japan debut in June 2024, generating controversy over whether it was appropriate for the label to market teenage girls through school aesthetics.

And underneath both the feminist reform and the commercial exploitation, another dynamic was operating: iljin culture, where uniform modifications signal not fashion identity or celebrity aspiration but social dominance and threat.

The iljin (일진)—school delinquents—use specific uniform styling codes: shortened skirts, unbuttoned shirts, luxury brand accessories, heavy makeup. These modifications don't mean the same thing as kogal fashion (individual style, subcultural belonging) or K-pop aesthetics (celebrity aspiration, consumer fantasy). They mean: I don't follow rules, I have power here, don't challenge me.

Unlike Japanese sukeban who lengthened skirts as explicitly feminist protest, and unlike kogals who shortened skirts as fashion statement, Korean iljin modifications serve a third function entirely: intimidation and hierarchy enforcement. The same formal elements—shorter skirts, looser fits—carry completely different social meanings depending on who's wearing them and in what context.

So by 2024, Korean school uniforms simultaneously signify:

Institutional control (original design purpose)

Celebrity aspiration (K-pop/K-drama aesthetics)

Feminist oppression (reform movement target)

Commercial tourism product (rental market)

Delinquent power signal (iljin culture)

Contested legal IP (NewJeans lawsuit)

Activist Kang Min-jin describes the impossible double-bind female students navigate: uniforms are supposed to signal "diligent, sexually innocent, hard-working student," while simultaneously the commercial culture demands they be "attractive, sexual, pleasant" for consumption. The same garment is supposed to desexualize and sexualize, control and liberate, enforce conformity and enable individual expression.

No wonder everyone's fighting about them.

THE ACCELERATED TIMELINE

Back to the Seoul courtroom, June 2024. HYBE and ADOR are still arguing over who owns the aesthetic of teenage girlhood packaged as intellectual property. Now, armed with the history, we can see what's actually being litigated.

The transformation took Japan roughly 75 years: sailor suits introduced in 1921, kogal emergence in 1993, peak commercialization by early 2000s. Korea compressed the same evolution into 40 years: branded uniforms return in 1986, BTS deploys student concepts in 2013, IP lawsuits by 2024. This isn't a "20-year lag" so much as accelerated parallel evolution via fundamentally different mechanisms.

Japan's transformation moved bottom-up: teenage girls modified uniforms in Shibuya streets, Egg magazine documented the phenomenon, commercial forces gradually recuperated the aesthetic into profitable products. The transformation began with youth agency and ended with commercial exploitation.

Korea's moved top-down: entertainment companies manufactured uniform aesthetics through K-pop debuts and K-drama styling, broadcast them via screens directly into student consciousness, legally protected the concepts as intellectual property. The transformation began with commercial production and filtered down to actual student experience.

But both nations developed remarkably similar patterns:

Youth modifications as resistance-through-style

Adult commercial appropriation of youth imagery

Nostalgia industries allowing consumption of idealized (or never-experienced) youth

Moral panics conflating fashion choices with sexual availability

Feminist counter-movements critiquing uniforms as instruments of gender oppression

The convergence suggests this isn't cultural diffusion—Korea copying Japan with a time lag—but parallel evolution driven by similar structural conditions. Both nations have:

Intense educational competition creating extended institutional control over youth

Collectivist cultures valuing group harmony over individual expression

Constrained spaces for youth autonomy, making clothing one of few available sites for identity negotiation

Powerful media industries capable of amplifying and commercializing youth aesthetics

Deep tensions around teenage sexuality, particularly female sexuality

These conditions create what scholar Brian McVeigh calls "uniforms as state and corporate interests projected onto student bodies." The institutional garment designed to enforce conformity becomes, precisely because of that repressive function, the most potent site for negotiating identity. Kawaii culture theorist Sharon Kinsella identifies the dynamic as youth rejection of "dominant 'male' productivist ideology of standardization, order, control, rationality." Modification becomes "demure, indolent little rebellion" against expectations of productivity and obedience.

But here's where Korea's accelerated timeline creates new problems Japan never faced: the commercial recuperation happened before most students had time to develop their own subcultural modifications. Kogals had a few years of authentic street culture before Egg magazine and commercial forces co-opted it. Korean students never got that window. The celebrity-manufactured aesthetic arrived fully formed, broadcast through screens, already commodified. There was no grassroots moment to recuperate because the aesthetic was always already corporate product.

Which means the feminist reform movement isn't just fighting institutional control (like students protesting dress codes everywhere). It's fighting a multi-billion won entertainment industry whose entire business model depends on packaging youth—specifically female youth—as aesthetic commodity. The NewJeans lawsuit makes clear that K-pop agencies consider "schoolgirl concept" valuable enough to litigate over. Reform threatens not just school regulations but commercial IP worth millions.

WHO OWNS THE TEENAGE GIRL?

Model @sio_0_show mounts an e-bike outside of a local Anguk-dong school.

Seoulacious photographed Korean model @sio.0.show in Bukchon yesterday doing an iljin concept in her own, original school uniform. A moment that we discovered as we wandered the area: a Korean high school student on her electric bicycle, white school shirt unbuttoned at the collar, dark shorts, Adidas socks, backpack with anime keychains dangling from the straps. She's parked outside a brick apartment complex in a neighborhood most tourists never visit, checking her phone between destinations.

This is—somehow, inexplicably—one of the most contested images in contemporary Korean culture.

Schools claim ownership: that uniform represents institutional authority, discipline, the civilizing project of education. Remove the shirt, attend class properly, conform.

K-pop agencies claim ownership: that aesthetic is intellectual property, carefully curated brand identity, legally protected concept. Our groups performed this look first, it's ours.

Uniform companies claim ownership: those clothes are consumer products bearing our trademarks, designed by our teams, marketed through our celebrity ambassadors. Elite, Smart, Ivy Club—we own the manufacturing and distribution rights.

The tourism industry claims ownership: that image is rentable nostalgia, content fodder, Instagram backdrop material available for ₩25,000 per day. Step right up.

Feminist activists claim ownership: that uniform is symbol of patriarchal oppression, gender discrimination made fabric, instrument of control that must be reformed or abolished. The wearer is victim requiring liberation.

Media claims ownership: that image is content to circulate, controversy to generate clicks, aesthetic to package and sell to audiences consuming Korean culture globally.

Iljin claim ownership: those modifications signal social dominance, threat, power within school hierarchies that exist parallel to institutional authority.

And the girl on the bicycle? She's navigating all of these claims simultaneously through her body. The way she wears the uniform—collar unbuttoned just so, socks positioned at precise height, accessories chosen to signal specific subcultural knowledge—represents what Blanco Borelli would call "situational agency." She can't control the corporate lawsuits or the rental industry or the feminist debates. But she can choreograph how her body performs the aesthetic, choosing which codes to activate, which meanings to emphasize.

Her body has become an urban interface—a compressed point where institutional control, celebrity aspiration, feminist resistance, commercial exploitation, and personal identity all collide. And through embodied performance—the accumulated tiny choices of how to wear, how to modify, how to move through space—she navigates forces vastly larger than herself.

This is the hidden sophistication that gets lost in debates about commodification. Yes, corporations sue over IP. Yes, tourists rent uniforms for Instagram. Yes, feminists critique oppression. All of that is true. But also true: young women are using the uniform as a site of aesthetic agency, performing identity through embodied knowledge that operates below conscious articulation. They're exercising what Borelli calls "aesthetic agency"—using the "different forms of value imposed on her skin, body, hair, or features" to create meanings that exceed what any single system intends.

The Korean women styling themselves in uniform aesthetics for Instagram aren't just being commodified—they're also commodifying themselves on their own terms, wielding the aesthetic as a form of cultural power. The rental industry customers aren't just consuming packaged nostalgia—they're also creating embodied experiences that generate new meanings. Even the feminist reformers aren't just victims of oppression—they're also agents forcing institutional change through organized resistance.

Model @sio_0_show takes up space in an Anguk-dong coffee shop in a way that is rude for her station.

The uniform has become what theorists call a "boundary object"—something that exists simultaneously in multiple social worlds, where each world attributes different meanings while maintaining the object's structural coherence. Schools see control. Corporations see IP. Tourists see experience. Feminists see oppression. Instagram models see aesthetic capital. Iljin see power. All of these meanings are real, all are simultaneously operating, all are being negotiated through the same pieces of fabric.

The NewJeans lawsuit isn't an aberration. It's the logical endpoint of a transformation that began in 1990s Shibuya and accelerated through Korea's celebrity-industrial complex. When institutional garments designed to eliminate distinction became contested commercial property and sites of embodied agency, we completed a circuit that reveals something profound about how East Asian capitalist modernity processes youth—particularly female youth.

School uniforms were meant to solve a problem: how do you create disciplined, productive citizens while appearing democratic and modern? The answer: make everyone look the same, enforce conformity through clothing, project state and corporate interests directly onto student bodies.

But the uniform's repressive function created the conditions for multiple forms of resistance and appropriation. Students modified garments to assert identity. Corporations recognized profit potential. Tourists consumed nostalgia. Feminists organized reform. Instagram models created content. And through it all, bodies kept performing, kept negotiating, kept finding tiny spaces of agency within massive systems of control.

Japan's transformation moved bottom-up over 75 years: street culture developed, magazines documented it, commercial forces recuperated it, moral panics ensued, feminist counter-movements emerged. Korea compressed the same evolution into 40 years, but inverted the direction: entertainment companies manufactured aesthetics, broadcast them through screens, legally protected them as IP, while street-level resistance operated through embodied performance rather than organized subculture.

The convergence isn't cultural diffusion but parallel evolution driven by similar structural conditions: intense educational competition, collectivist cultures valuing group harmony, constrained spaces for youth autonomy, powerful media industries, and deep tensions around female sexuality. These conditions create what scholar Brian McVeigh calls "uniforms as state and corporate interests projected onto student bodies." The institutional garment designed to enforce conformity becomes, precisely because of that repressive function, the most potent site for negotiating identity.

But here's where Korea's accelerated timeline creates dynamics Japan never faced: the commercial recuperation happened before most students developed their own subcultural modifications. There was no grassroots moment to co-opt because the aesthetic arrived pre-packaged. This means the feminist reform movement isn't just fighting institutional control—it's fighting a multi-billion won entertainment industry whose business model depends on packaging youth as aesthetic commodity.

The NewJeans lawsuit makes this explicit. When major corporations litigate over who owns "schoolgirl aesthetic," they're not protecting creative expression—they're protecting commercial rights to commodify female youth. This is what's at stake in the rental shops, the Instagram posts, the feminist protests, the iljin modifications: the question of who gets to define, control, monetize, and perform the meaning of being a teenage girl.

Her “Situational Agency”

Model @sio_0_show is indeed hazarding a fall in the Anguk subway station on the way out of school.

Somewhere in Seoul right now, a teenage girl is rolling her skirt waistband to shorten it before leaving for school. It's a gesture so automatic she probably doesn't think about it—just part of getting dressed, like brushing her teeth or checking her phone.

What she doesn't know: that gesture connects her to 1990s Shibuya street culture, to corporate IP litigation, to feminist reform movements, to tourism economics, to K-pop choreography, to Instagram aesthetic codes. That tiny modification—unconscious, undocumented, quickly reversed before walking past the school gates—is her wielding the only power she actually has.

The uniform was designed to make her invisible, identical, controlled. Instead, it made her body into an interface where massive social forces collide and compete. Whether that's liberation or exploitation depends entirely on your angle of analysis.

From the corporate perspective: success. The aesthetic is valuable enough to sue over, rent out, trademark, monetize.

From the institutional perspective: failure. The garment meant to enforce conformity became the primary site of resistance.

From the feminist perspective: ongoing struggle. Reform is achieving policy victories while commercial exploitation intensifies.

From the embodied perspective: agency within constraint. Young women can't change the systems but can choreograph how their bodies perform within them.

All of these perspectives are simultaneously true. The uniform isn't a problem with a solution—it's a dynamic site where multiple forms of power, resistance, commodification, and agency are constantly being negotiated through embodied performance.

The question "who owns the teenage girl?" has a simple answer: everyone claims ownership except teenage girls themselves. But that's only half the story. The other half is this: through embodied performance, through aesthetic agency, through the accumulated tiny modifications that transform institutional control into something approximating autonomy, teenage girls are also claiming ownership of themselves—one rolled waistband, one Instagram post, one carefully chosen sock height at a time.

The uniform can't be reduced to either pure commodification or pure agency. It's both, simultaneously, negotiated through bodies that have become interfaces between the individual and the institutional, the personal and the commercial, the resistant and the complicit.

In that space—that compressed interface where a Korean teenage girl's body meets corporate IP law, rental tourism, feminist reform, Instagram aesthetics, and K-pop choreography—something emerges that exceeds any single system's intentions. Not freedom, exactly. Not pure oppression either. Something more like what Blanco Borelli calls "situational agency"—the power to choreograph oneself into being even when all the music is written by others.

Whether that's enough depends on who's wearing the uniform and what they're trying to say with their body when they do.

Model @sio_0_show flouts institutional and social authority in a “Protected Learning Environment Zone.”