The ₩82 Trillion Woman: Why Korean Fashion Finally Noticed Who Actually Buys the Clothes

Something strange started happening at Olive Young stores around 2018. The trendy health and beauty chain—designed for 20-something women hunting Instagram-worthy K-beauty finds—noticed an unexpected customer pattern in their transaction data. Their highest-spending customers, the ones Korean retailers call "큰 손" (keun son, literally "big hands" but meaning big spenders), weren't the young women in the marketing materials.

They were their mothers.

Women in their 40s, 50s, and 60s were walking into these youth-focused stores and systematically outspending everyone else. They bought lip tints alongside anti-aging serums. They purchased trendy nail stickers with their wrinkle treatments. They shopped with their daughters, creating basket sizes that made everyone else look like window shoppers. By 2024, customers over 40 represented 13.1% of Olive Young's customer base—up from single digits in 2012—and their year-over-year growth rates matched the twentysomethings everyone was designing stores for.

The color cosmetics revelation hit hardest: 40+ women increased purchases 68% year-over-year. These weren't just buying "age-appropriate" products. They were buying everything.

Welcome to the ajumma economy. It's been here the whole time. Korean fashion and beauty just spent the last decade pretending not to notice.

The Numbers Don't Lie, But The Marketing Does

Middle-aged Korean women aged 40-60 control approximately 64% of South Korea's total income and account for 63% of national consumption spending. They maintain the highest monthly household expenditure at ₩3.09 million (for those in their 40s) and the highest income at ₩4.51 million. In Korea's ₩82.88 trillion fashion market, women in their 50s command 23.6% of total market share—the single largest demographic. Add 40-year-olds at 22.8%, and the combined 40-50s age group captures 46.4% of all fashion expenditure.

By contrast, the heavily marketed 20-something demographic? They command 15.8% of fashion spending. Less than half the middle-aged share.

Yet walk through a Korean department store, flip through fashion magazines, watch cosmetics commercials, and you'd think 20-year-olds were the only people with wallets. The strategic absurdity becomes clear: brands harvest profits from middle-aged consumers while investing those earnings into marketing to younger demographics with dramatically lower spending power.

This isn't ignorance. It's something worse: calculated invisibility.

How Did We Get Here? A Century of Women Holding The Money While Men Held The Cameras

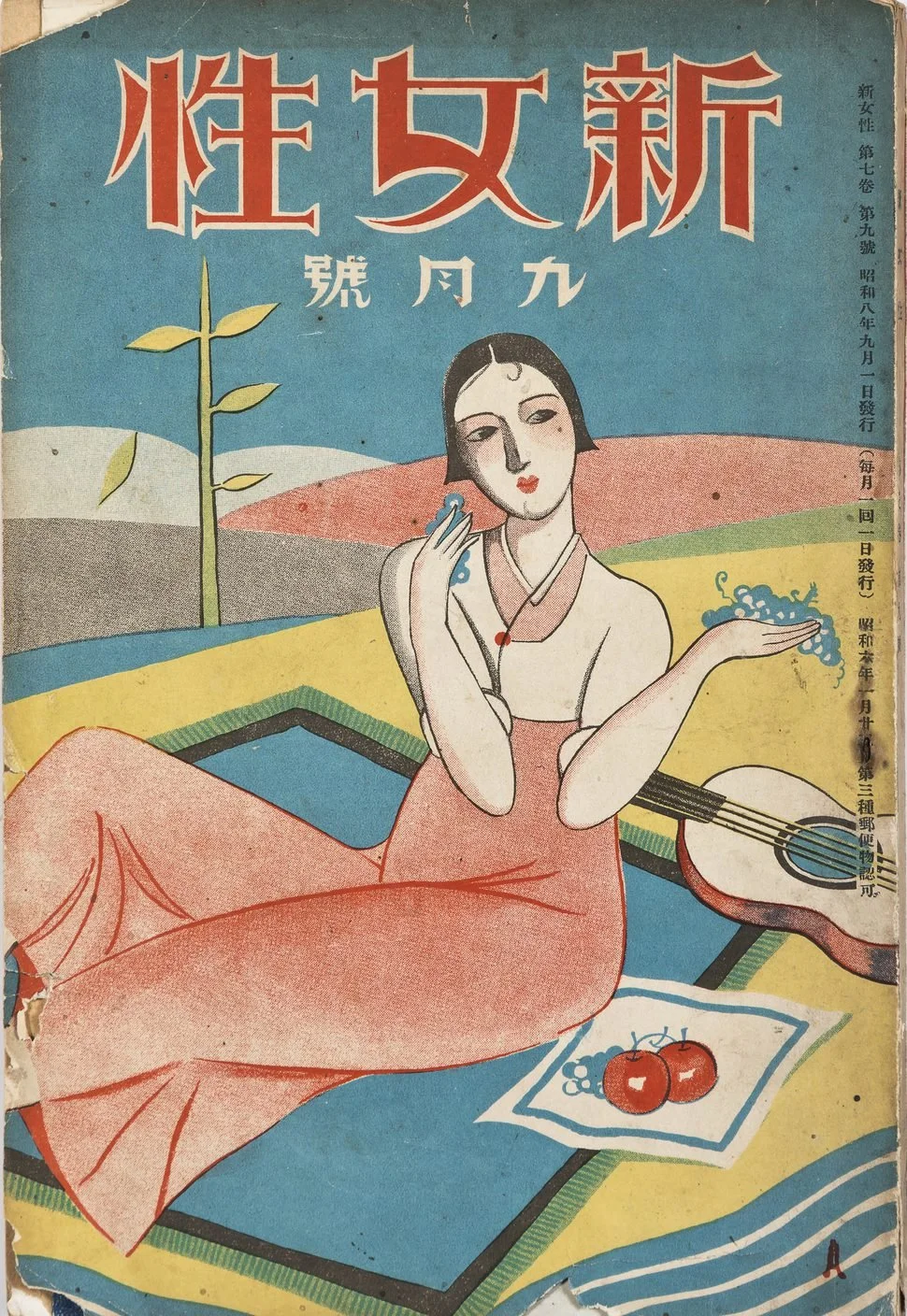

The first modern women's magazine in Korea was "Shinyeoseong" (신여성, meaning "New Woman"), which was published starting in 1922. It emerged during the Japanese colonial period and focused on new knowledge, women's education, and the advancement of women in society.

Understanding the ₩82 trillion woman requires tracing a century-long arc. During the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), the "Modern Girl" (모던걸) phenomenon emerged among educated urban women who used consumption—Western-style fashion, cosmetics, bobbed haircuts—as expressions of forbidden modernity under oppression. These women had little independent income but enormous symbolic power. Every lipstick became political resistance.

Post-liberation industrialization (1960s-1970s) created the "Factory Girls"—young women whose textile and electronics assembly wages fueled Korea's economic miracle while financing brothers' education over their own. Their consumption remained constrained to survival plus modest luxuries (cosmetics, fashion items), but for the first time, they earned independent wages and made independent purchasing decisions. These women learned to manage money because nobody else would do it for them.

The democratization era (1980s-1990s) transformed everything. Female labor force participation jumped from 34.4% (1965) to 48.1% (1999). Female university enrollment soared from 4% (1966) to 61.6% (1998). Professional and managerial positions for women increased from 2% (1975) to 12.6% (1998). Higher education translated to professional careers, which generated purchasing power and household financial decision-making authority.

Then came the 1997-98 IMF crisis—the moment when middle-aged women's economic role became undeniable. When unemployment tripled and 80% of households suffered income decline, middle-aged women disproportionately entered or re-entered the workforce to anchor household finances during the worst economic crisis in modern Korean history. They opened beauty shops, convenience stores, fried chicken joints when stable employment disappeared. The famous Gold Collecting Campaign, where a quarter of the population sold jewelry to help repay national debt, symbolized women's economic sacrifice and power—they controlled household assets worth mobilizing for national salvation.

The women who navigated that crisis are the 40-60-year-olds controlling 64% of national income today. They survived compressed modernity, economic collapse, and cultural transformation. They have money, they know how to use it, and they're not asking permission to spend it anymore.

The Young Forty Revolution: When The Customer Shows Up But Isn't In The Marketing Plan

The emergence of the "영포티" (Young Forty) consumer archetype marks a fundamental behavioral shift. These economically stable 40-60-year-olds maintain youthful sensibilities while wielding substantial purchasing power. Unlike previous generations who devoted earnings primarily to children's education and family needs, contemporary middle-aged women increasingly invest in themselves—hobbies, travel, aesthetic consumption, personal development.

This generation exhibits higher rates of remaining unmarried or divorced, reduced spending on children's supplementary education compared to their predecessors, and explicit embrace of "나에게 투자하는" (investing in myself) consumption philosophy. They willingly allocate resources to appearance, health, and quality of life improvements without the guilt that constrained earlier cohorts.

Their shopping patterns reveal sophisticated omnichannel behavior. Rather than loyalty to traditional department store counters or door-to-door sales representatives (방판), Young Forty consumers actively seek "가성비" (cost-performance ratio)—quality products at fair prices regardless of channel. A 48-year-old consumer interviewed by industry publications described shopping at Olive Young with her university-age daughter, purchasing products suitable for both generations and creating emotional bonding through shared aesthetic consumption.

Purchase basket analysis shows middle-aged women favor simultaneous multi-category buying: a typical transaction bundles skincare products with health functional foods, anti-hair loss treatments, scalp care systems, and increasingly, color cosmetics traditionally marketed to younger women. This efficiency-driven consolidation reflects time-conscious consumers with disposable income who prefer comprehensive solutions over multiple shopping trips.

Seoul metropolitan data tracking five-year spending trajectories (2019-2024) demonstrates the shift in real-time. Those aged 50-54 increased total spending by 51%, the 55-59 cohort by 57.5%, and 60-64-year-olds by 63.1%. Online spending growth proved even more dramatic: 119.2% increase for 50-54-year-olds and 141.7% for 60-64-year-olds, shattering assumptions about digital hesitancy. These middle-aged women now shop online at remarkable rates—56% for those in their 50s and 47% for 40-year-olds—often exceeding younger demographics' online penetration in certain product categories.

Why Sulwhasoo Hired a 20-Year-Old to Sell Wrinkle Cream to Your Mom

The Sulwhasoo case reveals the economic absurdity at the heart of Korean beauty marketing. Sulwhasoo—a ₩2 trillion mega-brand built on middle-aged loyalty, premium ginseng-based formulations, and efficacy-driven positioning for mature skin—made a calculated pivot around 2022. The brand systematically "de-aged" its image: hiring younger celebrity ambassadors, redesigning packaging for trendy minimalism, repositioning products to attract consumers in their 20s-30s.

Why would a brand abandon its core consumers at the height of profitability? Because Korean beauty culture pathologizes middle-age so completely that brands fear "ajumma화" (becoming an ajumma brand) as a commercial death sentence. Sulwhasoo bet that younger consumers would embrace a premium brand while hoping loyal older customers would accept the pivot without defection—or continue buying while the brand pretended they didn't exist.

This pattern repeats across beauty and fashion categories. Premium brands harvest middle-aged revenue while investing those profits in youth marketing. Retailers design for young shoppers then scramble to accommodate middle-aged "big spenders" who arrive unexpectedly. Innovation cycles prioritize trendy formats over addressing actual aging-skin challenges that middle-aged consumers specifically want solved.

The cultural mechanism driving this economic irrationality centers on the "ajumma" stigma itself. The term—literally meaning "married woman" or "aunt"—carries connotations ranging from affectionate respect to dismissive stereotyping. Traditional ajumma characteristics (practical short permed hair, comfortable athletic wear, assertive public behavior, family-first priorities) became objects of ridicule in youth-obsessed Korean popular culture. The "ajumma perm" and visor emerged as visual shorthand for unfashionable middle-age.

Recent rebranding efforts show mixed results. Surveys show 41% now associate ajumma/ajae terms with positive traits (kindness, stability, hard-working), yet negative associations persist strongly enough that brands avoid the terminology commercially. The "Young Forty" framing represents a compromise: acknowledging middle-aged consumers while emphasizing their youthful sensibilities rather than celebrating aging itself.

The Demographic Inevitability Nobody Wants To Plan For

Korea entered "super-aged society" status in December 2024 with 20% of population over 65, while birth rates collapsed to 0.72 (2023)—the world's lowest. Population aged 40+ comprises approximately 50% of total population, a proportion projected to increase for decades. The middle-aged consumer segment will expand absolutely and relatively.

Within decades, the youth demographic brands obsess over will represent a tiny fraction of purchasing power while middle-aged and elderly consumers dominate. You can't build sustainable domestic business when your target demographic represents 15.8% of market share and shrinking while the 46.4% majority you ignore keeps growing wealthier and larger.

The cosmetics industry's explosive growth—₩17.5 trillion production value in 2024, up 20.9% year-over-year—derives substantially from middle-aged consumption. Functional cosmetics (anti-aging, whitening, wrinkle improvement) account for 37.5% of total production value, categories purchased overwhelmingly by 40+ consumers. The color cosmetics segment saw middle-aged women increase purchases 68% year-over-year, the fastest-growing demographic in a category traditionally youth-dominated.

Fashion market dynamics reinforce middle-aged dominance but remain strategically under-optimized. The ₩82.88 trillion total market shows 40-50-year-olds controlling 46.4% combined share, yet fashion innovation, marketing, and design prioritize younger consumers. The casualwear category (₩22.47 trillion, 27.1% of market) and sportswear (₩22.65 trillion, 27.3%) appeal across generations but lack middle-aged-specific styling, sizing, or positioning.

Luxury fashion shows similar patterns: wealthy 40-60-year-old women remain core luxury consumers (Korea's $16.8 billion luxury market, $327 per capita spending—the highest globally), but brands increasingly target younger aspirational buyers rather than current premium spenders.

The Decision-Making Multiplier: How One Middle-Aged Woman Controls Multiple Wallets

Middle-aged women's purchasing dominance extends beyond personal consumption to household financial control. Global research from Harvard Business Review indicates women command 94% of household furniture decisions, 92% of vacation choices, 60% of automobile purchases, and 51% of electronics—categories traditionally considered male domains.

Korean household dynamics follow similar patterns with culturally specific intensification: 87.2% of newlywed households are now dual-income families, translating to shared or female-dominant financial decision-making. Contemporary 40-60-year-old Korean women frequently out-earn spouses or contribute equally, particularly in professional and managerial positions this generation entered at unprecedented rates.

Their financial literacy—honed through managing household budgets for decades combined with professional experience—makes them sophisticated evaluators of value propositions. Consumer research reveals middle-aged women prioritize brand trustworthiness and product efficacy over pure price or pure prestige, meticulously research ingredients and formulations, and rely heavily on peer recommendations through online communities (맘카페/mom cafes) and social networks rather than celebrity endorsements.

The "proliferation effect" magnifies their market influence: when a middle-aged woman identifies an effective product, she recommends it within her social circle, creating cascading adoption patterns. Unlike younger consumers whose purchasing experiments reflect personal identity expression, middle-aged women's recommendations carry weight of experience and perceived objectivity. A 50-year-old sharing a skincare discovery in a mom cafe generates more sustained purchasing than a beauty influencer's sponsored post.

Yet brands systematically undervalue and under-cultivate these organic advocacy networks, instead pouring marketing budgets into influencer partnerships with far lower conversion rates.

Who Actually Figured It Out (And Why Everyone Else Should Pay Attention)

A handful of brands navigated the middle-aged positioning challenge successfully, revealing viable commercial strategies that respect this demographic while capturing their spending power.

LG Household & Health's "The History of Whoo" (후) represents unapologetic premium positioning for middle-aged women without youth-chasing. The brand's "royal court cosmetics" concept targets 40-60-year-olds explicitly, maintains traditional luxury positioning with minimal celebrity model usage, and became LG H&H's mega-brand generating over 50% of the company's cosmetics revenue. The History of Whoo achieved ₩2 trillion revenue faster than any Korean brand, proving that premium middle-aged consumers would pay substantial premiums for products and positioning that respected their preferences.

Olive Young's evolution from youth-focused H&B store to "Young Forty" destination illustrates retailers adapting to economic reality. Initially targeting exclusively 20-30-year-olds with trendy, affordable products, management recognized that 40+ consumers arriving unexpectedly in stores demonstrated higher average transaction values and basket sizes. Rather than maintaining youth exclusivity, Olive Young adjusted merchandising to accommodate cross-generational shopping, emphasized "가성비" (value-for-money) that resonated with experienced consumers, and expanded category breadth to enable one-stop shopping.

The Japanese success story of "The Golden Shop" (ザ・ゴールデンショップ)—though ultimately discontinued—revealed authentic middle-aged positioning's commercial potential. Launched by Cosumeport in 2011 after recognizing that middle-aged women comprised majority customers at "young" drug stores, The Golden Shop created pharmacy-style health and beauty stores exclusively targeting 40-60-year-olds. The brand positioned products (₩10,000-30,000 price range) around natural ingredients appealing to mature consumers—makgeolli (rice wine), fermented black garlic, silkworm extract, red ginseng—and framed the target demographic as "Golden Age" consumers actively enjoying life with economic capability rather than fighting age with desperation. The Golden Shop achieved 40%+ year-over-year growth and operated 391 stores in Japan by July 2013.

These successes share common elements: acknowledging the target demographic explicitly, creating shopping environments free from youth-culture intimidation, offering products that solve actual aging-related concerns rather than promising impossible reversals, and marketing with messages that respect intelligence and experience.

AJUMMODELS: Why Seoulacious Is Making Middle-Aged Women The Face of Fresh

But here's what nobody else is doing: treating middle-aged Korean women as the aesthetic vanguard they actually are.

At Seoulacious, we're not just analyzing the ₩82 trillion woman. We're putting her on the cover. We're calling them AJUMMODELS (아줌마모델), and they're going to be the freshest, edgiest thing in Korean fashion media. Not because we're being charitable to an underserved demographic. Because middle-aged Korean women actually wear the most interesting clothes in Seoul if you bother to look.

The global fashion industry is already figuring this out. The "senior models" trend has exploded over the past five years, with approximately 75% of top Paris and Milan runway shows now including at least one older model. Designers like Batsheva Hay cast exclusively over-40 models for entire collections. Tom Ford's Forever Love campaign featured mature models. Joni Mitchell fronted Saint Laurent ads at 71. Brands like L'Oréal signed Helen Mirren (69) and Twiggy (65) as spokeswomen. The fashion industry's ideal has shifted "from fantasy to wearability"—and mature models bring authenticity that teenage faces can't deliver.

The economics make brutal sense: the "Silver Generation" (over 50) will drive 48% of global spending growth in 2025, controlling 72% of US wealth. Yet 60% of fashion executives still plan to prioritize younger consumers. This disconnect between strategy and reality creates opportunities for whoever figures out authentic middle-aged positioning first.

Korea has senior models too—Park Nam-sun (69), Kang Jeong-ae, Jeon Se-zin—walking Seoul's runways with cropped silver hair and natural wrinkles, refusing artificial enhancements. The first Seoul Senior Model Fashion Festival happened in 2024. The market is waking up.

But Seoulacious isn't waiting for "senior model" trend think pieces to trickle into Korean fashion media. We're building AJUMMODELS as an aesthetic category from the ground up because middle-aged Korean women already perform the most sophisticated street style in the country. They layer technical fabrics with luxury accessories. They mix outdoor brands with formal pieces. They take risks with proportion and silhouette that 20-year-olds won't touch because they're too worried about trend alignment.

Consumer research describes middle-aged women's aesthetic preferences as "simple, textured, unpretentious, daring, beautiful." That's not "age-appropriate fashion" euphemism. That's actually describing what makes Korean style distinctive: the confident mixing of high and low, the unexpected proportions, the technical fabric obsession, the refusal of pure minimalism or pure maximalism. Middle-aged Korean women wear Korean style better than anyone else because they have the confidence and resources to commit to the bit without hedging.

Korean ajummas already revolutionized global coffee culture—Korea has the highest per capita coffee consumption in Asia because middle-aged women transformed cafes into social infrastructure. They built the PC bang culture. They created the jimjilbang phenomenon. They made Korean supermarkets into theater. Every time middle-aged Korean women collectively decide something is worth their time and money, entire industries get created.

So why wouldn't they be fashion models?

The aesthetic move here isn't "inclusion" or "representation" or any other framework that positions middle-aged women as charity cases who deserve visibility. The move is recognizing that in a culture obsessed with consumer sophistication, the consumers with the most sophisticated taste are the ones with decades of purchasing experience and disposable income to exercise it.

AJUMMODELS will show 40-60-year-old women styling the trends Seoulacious covers—not as "here's how older women can adapt youth trends" but as "here's the woman who actually makes this trend work." When we shoot garter stockings in Hongdae, we're putting them on a 50-year-old who understands proportion better than anyone half her age. When we cover emerging Korean designers, we're showing how women with real bodies and real money actually wear the clothes.

This isn't a side project or a token editorial series. AJUMMODELS is one of our core aesthetic modes because the ₩82 trillion woman isn't a demographic to be served. She's the taste-maker fashion media forgot to cover while they were photographing teenagers outside Seoul Fashion Week.

Fashion's biggest blind spot is Seoulacious's biggest opportunity. While everyone else keeps shooting 19-year-olds who can't afford the clothes they're modeling, we'll shoot the women who actually buy them. And we'll prove that middle-aged women bring something fresher, edgier, and more essentially Korean to fashion photography than any number of doe-eyed Gen Z influencers ever could.

The future of Korean fashion looks like a 52-year-old woman in Arc'teryx, Loewe, and garter stockings walking through Sadang Station at 2pm on a Wednesday. If you don't see her, that's your problem. Seoulacious sees her perfectly.

What Comes Next When You Can't Pretend Anymore

Korea's demographic crisis will eventually force a reckoning. The numbers don't lie and they're not getting better: 0.72 birth rate, super-aged society status, shrinking youth cohorts, expanding middle-aged and elderly population. Within decades, the youth demographic brands obsess over will represent a tiny fraction of purchasing power while middle-aged and elderly consumers dominate.

Brands that figure out authentic middle-aged positioning now—products combining proven efficacy with modern aesthetics, marketing through channels middle-aged women actually use, messaging that respects intelligence and experience, cultivation of peer recommendation networks that drive purchasing decisions more effectively than celebrity endorsements—will gain structural advantages.

Those clinging to youth-only strategies will face declining addressable markets. The opportunity sits waiting: sophisticated middle-age positioning that sheds both youth-chasing and condescension. Products that acknowledge aging happens and offer quality solutions rather than miracle cures. Fashion that serves bodies and lifestyles of women in their 40s-60s without presuming they want to dress like their mothers. Beauty marketing that uses age-appropriate models without making age the product's defining characteristic.

"Simple, textured, unpretentious, daring, beautiful"—that's how consumer research described middle-aged women's aesthetic preferences. Not frumpy formal wear. Not desperate youth-mimicry. Contemporary style that acknowledges their actual lives, bodies, and desires.

The brands that crack this code will own the next decade of Korean consumer markets. The brands that don't will keep selling anti-aging cream using 20-year-old faces while wondering why their core customers quietly defect to whoever finally takes them seriously.

The ajumma economy isn't coming. It's already here. It's been here. Korean fashion and beauty just spent the last decade looking everywhere else while middle-aged women patiently waited for someone to notice they had all the money.

Time to start paying attention to the ₩82 trillion woman. She's been shopping this whole time. She's just been doing it while you pretended not to see her.

And now? She's going to be on the cover of Seoulacious wearing the freshest fit you saw all week. Because it turns out that when you stop photographing children and start photographing women with taste, money, and zero fucks left to give, fashion gets a lot more interesting.

Welcome to AJUMMODELS. Welcome to the future of Korean fashion media. Welcome to the aesthetic economy that was always there—you just had to look at someone besides a teenager to see it.