The fashion magazine died just as it learned to think

The most radical idea in media history was this: what if we assumed teenage girls were intelligent? When Lauren Duca's essay "Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America" racked up 1.2 million views on Teen Vogue in December 2016—displacing the previous record-holder, "How To Apply Glitter Nail Polish The Right Way"—something profound had happened. A fashion magazine for teenagers had produced more incisive political analysis than legacy news outlets. And within a year, its print edition would be dead.

This is the central tragedy of fashion journalism's evolution: the model collapsed precisely when it was becoming something sharper, stranger, and more culturally necessary than it had ever been. Teen Vogue under Elaine Welteroth didn't just cover politics—it proved that the entire framework separating "serious" and "frivolous" content was built on condescension. The same readers who wanted to know about thigh-high boots also wanted to understand structural inequality. They always had. Nobody bothered to ask.

But Teen Vogue wasn't alone in this revelation. Across decades and continents, a constellation of publications had been conducting the same experiment: Sassy talking to teenage girls like humans, i-D documenting street style as cultural theory, Bitch Magazine dissecting pop culture's feminist implications, Adbusters culture-jamming corporate advertising into submission. Each proved that treating audiences as intelligent co-conspirators—rather than passive consumers—could create something culturally transformative.

The question now is whether that experiment can continue. The answer is SEOULACIOUS—and understanding why requires understanding what these magazines were actually doing.

The conspiracy to treat readers as human beings

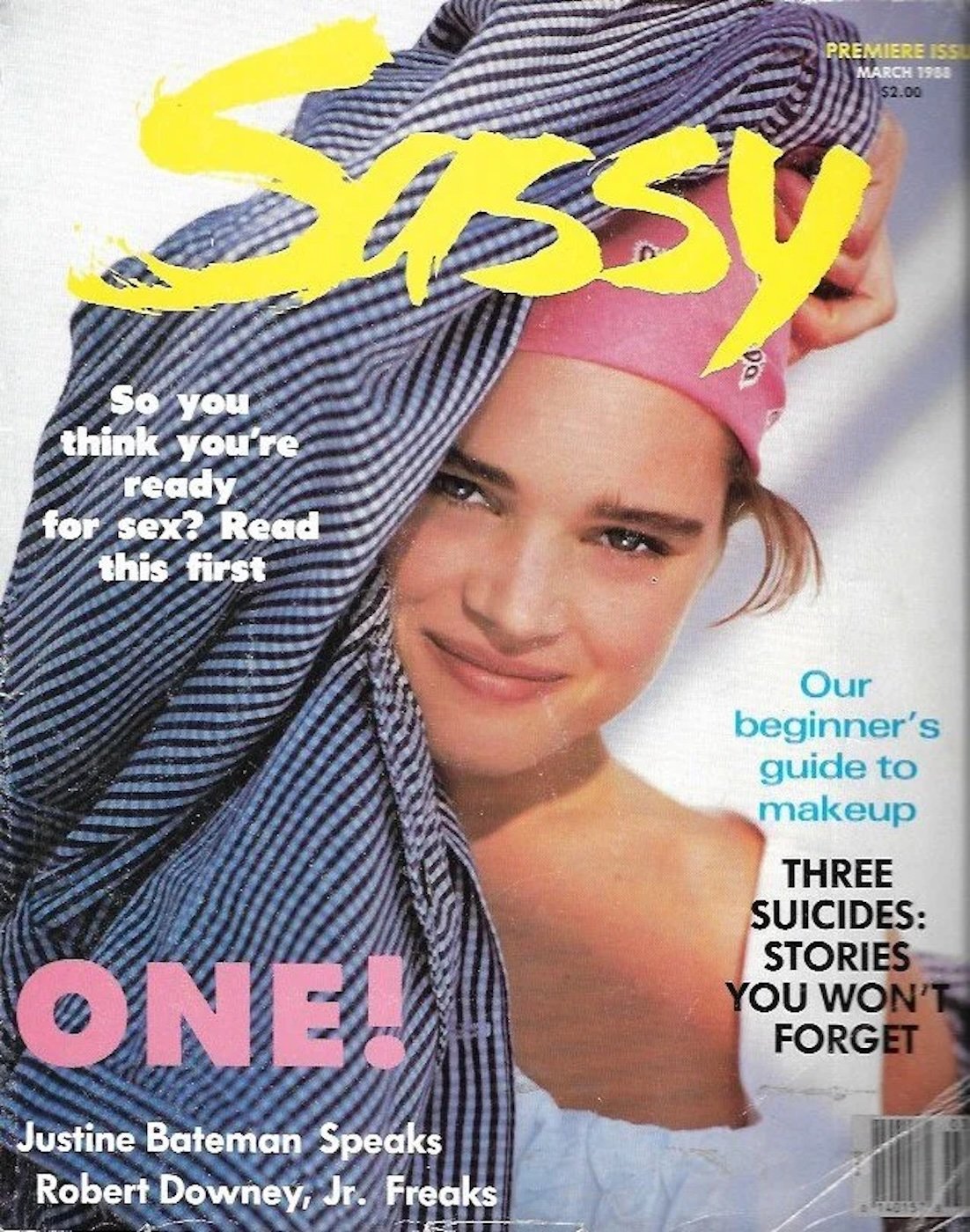

Jane Pratt was twenty-four years old when she launched Sassy in March 1988, making her the youngest editor-in-chief of a national magazine in American history. She had written in her journal at fifteen: "I want to start a magazine (with friends)." The reason was simple—she wasn't seeing herself in existing teen magazines. Seventeen and YM talked at their readers like concerned guidance counselors. Sassy talked with them like an older sister who'd been through it.

The first issue included "Losing Your Virginity: Read This Before You Decide"—frank, non-judgmental sex education that treated sexual decision-making as something teenagers might actually think about rather than simply be warned against. Issue three featured photographs of gay teenage couples under the headline "And They're Gay"—radical for 1988, when gay teenagers were essentially invisible in mainstream media. The magazine covered AIDS, masturbation, eating disorders, mental health, and politics alongside fashion spreads that emphasized vintage finds and indie aesthetics over unattainable luxury.

What made Sassy legendary wasn't individual articles but its foundational assumption: that teenage girls possessed the same cognitive complexity as adult humans. The magazine's "It Happened to Me" column published unedited first-person essays from readers because, as Pratt explained, "teenagers are going to trust someone else their age who's going through it... not someone who has a degree." Staff signed articles with first names only. Letters to the editor were addressed "Dear Jane." The aesthetic was intimacy, not authority.

This seems obvious now. It wasn't then. The conservative backlash was immediate and devastating. Women Aglow, an evangelical women's group, organized boycotts. Focus on the Family accused editors of promoting promiscuity. The Moral Majority published calls urging pressure on advertisers. Pre-printed note cards flooded advertising departments. Within months, Sassy lost the majority of its major advertisers and was pulled from 70% of newsstands nationwide. The magazine limped along for eight years before being absorbed into the generic Petersen's TEEN in 1997.

But its DNA survived—not just in Teen Vogue but in an even more radical descendant.

Pop culture as feminist battleground

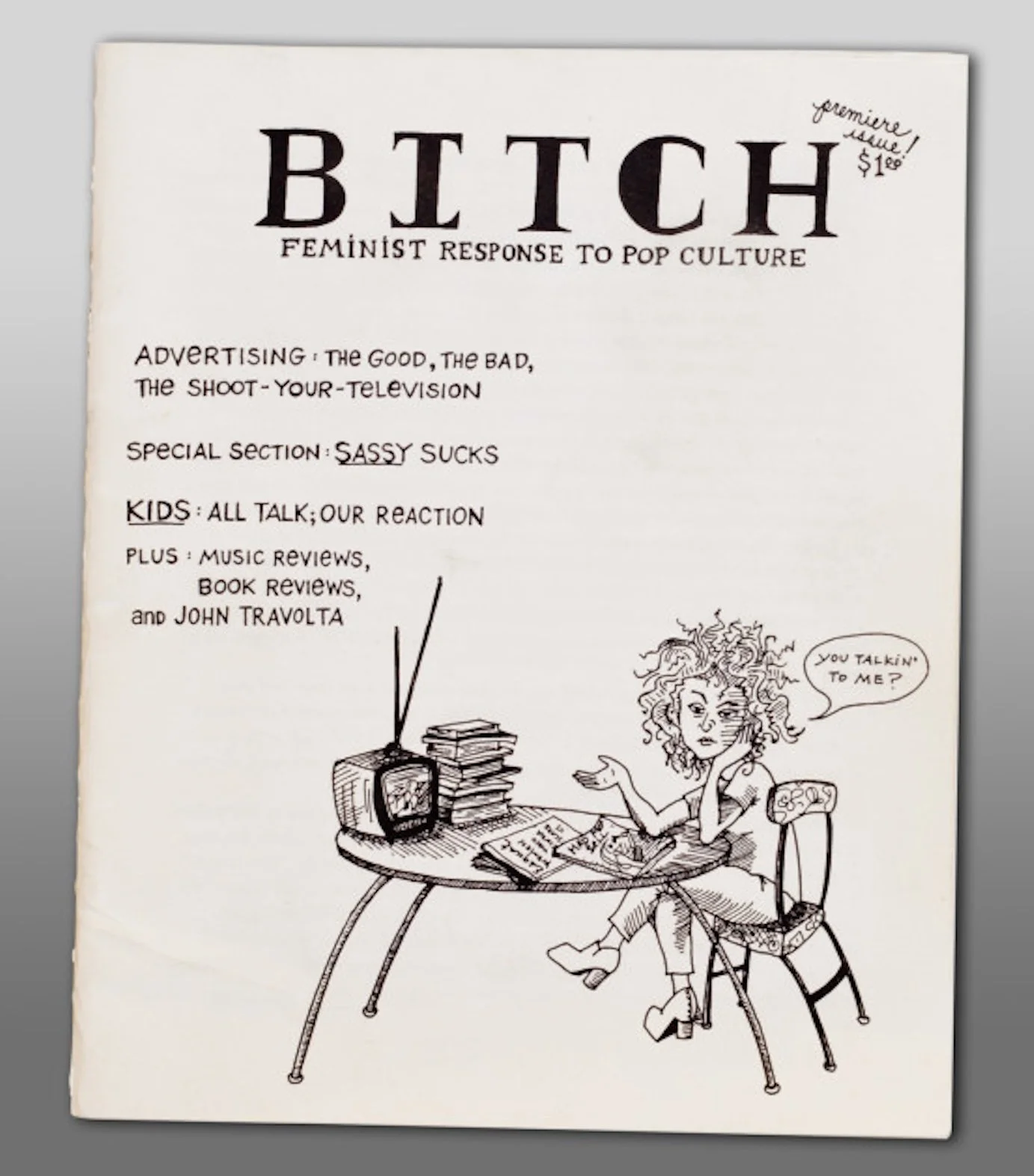

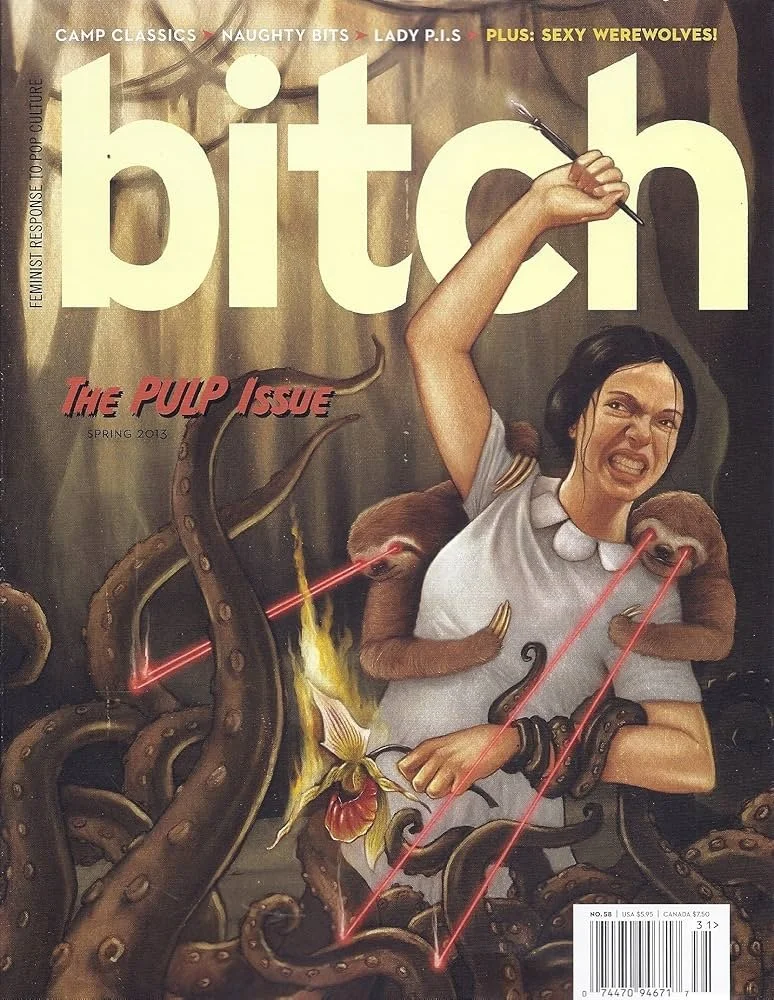

In 1996, Lisa Jervis and Andi Zeisler—high school friends who'd both interned at Sassy—reached their breaking point. One too many episodes of Beverly Hills, 90210. One too many copies of Esquire. One too many moments of watching pop culture deliver insidious sexist messages wrapped in glossy entertainment. They decided to create the magazine they wanted to read: Bitch: Feminist Response to Pop Culture.

The first issue was printed at Berkeley's Krishna Copy, 300 copies distributed from Jervis's 1977 station wagon. The name itself was "anticipatory retaliation"—inspired by the LGBTQ community's reclamation of "queer," they claimed "bitch" before it could be weaponized against them. More than that: they wanted a title that would intrigue people, that worked as both verb and noun, that announced this publication wouldn't apologize for being difficult.

Bitch positioned itself as the antidote to Cosmopolitan and Vogue—magazines that had spent decades patronizing women with the assumption that they cared only about makeup tips and pleasing men. Instead, Bitch applied rigorous cultural analysis to the pop landscape, examining everything from MTV programming to the gender politics of Disney films. The editors didn't reject consumer culture—they loved it, unabashedly—but they insisted on interrogating it, on asking what messages lurked behind favorite TV shows, movies, music, and advertising.

What made Bitch revolutionary was its refusal to separate pleasure from critique. You could love something and simultaneously analyze its problematic elements. You could find Martha Stewart's domestic aesthetics compelling while questioning the labor politics they concealed. You could enjoy romantic comedies while recognizing how they naturalized patriarchal relationship structures. This both/and thinking—what the editors described as being "unabashed in its love for the guilty pleasures of consumer culture and deeply thoughtful about the way the pop landscape reflects and impacts women's lives"—created a new mode of feminist media criticism.

And crucially, Bitch proved the same thing Sassy had: young women would engage with serious ideas if you didn't condescend to them. By the early 2000s, circulation reached 35,000. In 2001, Jervis and Zeisler secured funding to work on the magazine full-time and established it as a nonprofit. In 2011, it won an Utne Reader Independent Press Award for Best Social/Cultural Coverage. The magazine survived 26 years before economic pressures finally killed it in 2022.

The lesson: feminist cultural criticism could be intellectually rigorous AND witty AND accessible. The framework separating academic feminism from popular entertainment was artificial. Anyone who cared about TV or music or fashion already had the tools to analyze it critically—they just needed permission and practice.

Jamming the machine

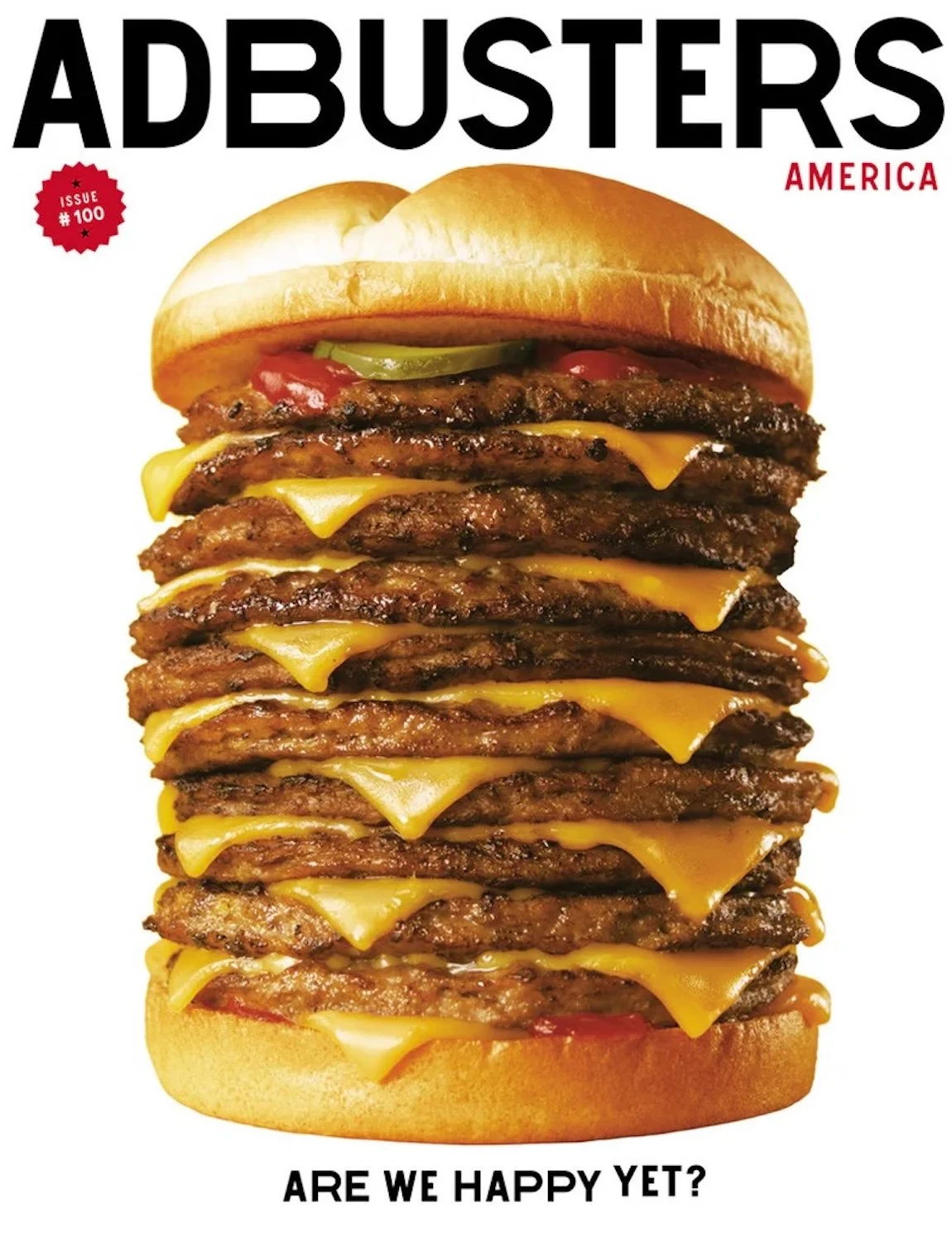

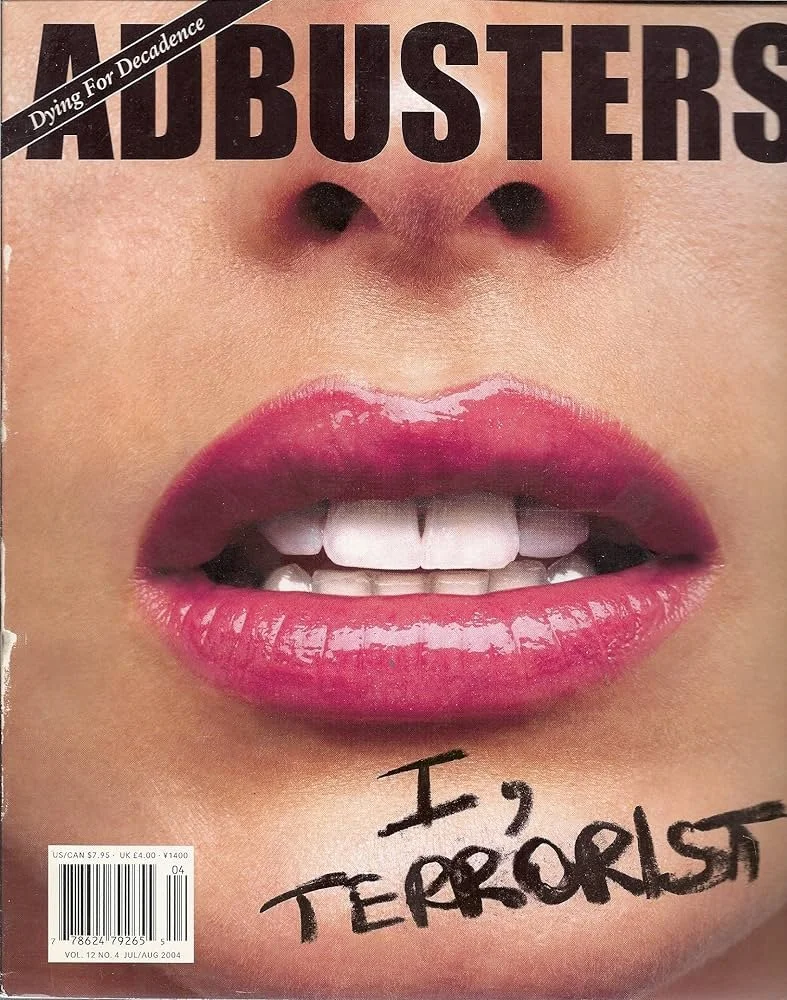

While Sassy and Bitch were proving that editorial content could be radical, Adbusters was attacking the very structure of magazine publishing itself. Founded in Vancouver in 1989 by Kalle Lasn and Bill Schmalz, Adbusters adopted a confrontational stance: they would use advertising's own techniques against it, turning the weapons of consumer capitalism back on the system.

The magazine described itself as "the journal of the mental environment." Lasn's argument was simple and devastating: you can't recycle and call yourself an environmentalist while watching four hours of television pumping consumption messages into your brain. Consumer capitalism was colonizing not just physical space but psychological space, and that mental pollution required the same activist response as environmental degradation.

Culture jamming—the magazine's primary tactic—meant hijacking commercial messages to reveal their underlying ideology. Adbusters would take recognizable advertising campaigns and subtly alter them to expose their manipulative techniques. A Nike ad featuring Tiger Woods's smile morphed into the Nike swoosh, forcing viewers to see how Woods had become a product. Tobacco company advertisements were parodied to show their actual health consequences. The goal wasn't just criticism but intervention—literally jamming the flow of corporate messages, creating what Lasn called "technical events" that forced people to stop and question consumption patterns.

Aesthetically, Adbusters was stunning. Every issue was a design experiment, using the visual language of high-end advertising to subvert advertising itself. The magazine had no ads (obviously), which meant it survived entirely on reader support—proving that anti-consumerist media could exist outside corporate funding structures. The masthead changed constantly. The barcode moved around the cover, sometimes incorporated into imagery. Lots of white space. Politically charged imagery. It looked like what would happen if a fashion magazine became politically radicalized.

More than any other publication, Adbusters proved that form and content were inseparable. You couldn't critique consumer capitalism using the same tired layouts and editorial approaches as mainstream magazines. The revolution required new aesthetics, new ways of organizing information, new relationships between image and text. And crucially: honest visual language. Adbusters didn't photograph products with the soft, seductive lighting of luxury advertising—they showed them starkly, sometimes grotesquely, in ways that revealed rather than concealed. The aesthetic was confrontational. Uncompromising. It refused to make consumption look beautiful. When Adbusters launched Buy Nothing Day in the 1990s—challenging people to abstain from shopping for 24 hours—most television networks refused to air their advertisements, with CBS citing "current economic policy in the United States" as justification. The message was clear: activism disguised as advertising was more threatening than advertising itself.

Adbusters would later inspire Occupy Wall Street with a simple blog post and hash tag in July 2011. A magazine with ten employees in Vancouver created a global protest movement. This was culture jamming at scale—using viral techniques to interrupt business as usual, to create space for questioning capitalism's inevitability.

Style as ideology, clothing as cultural theory

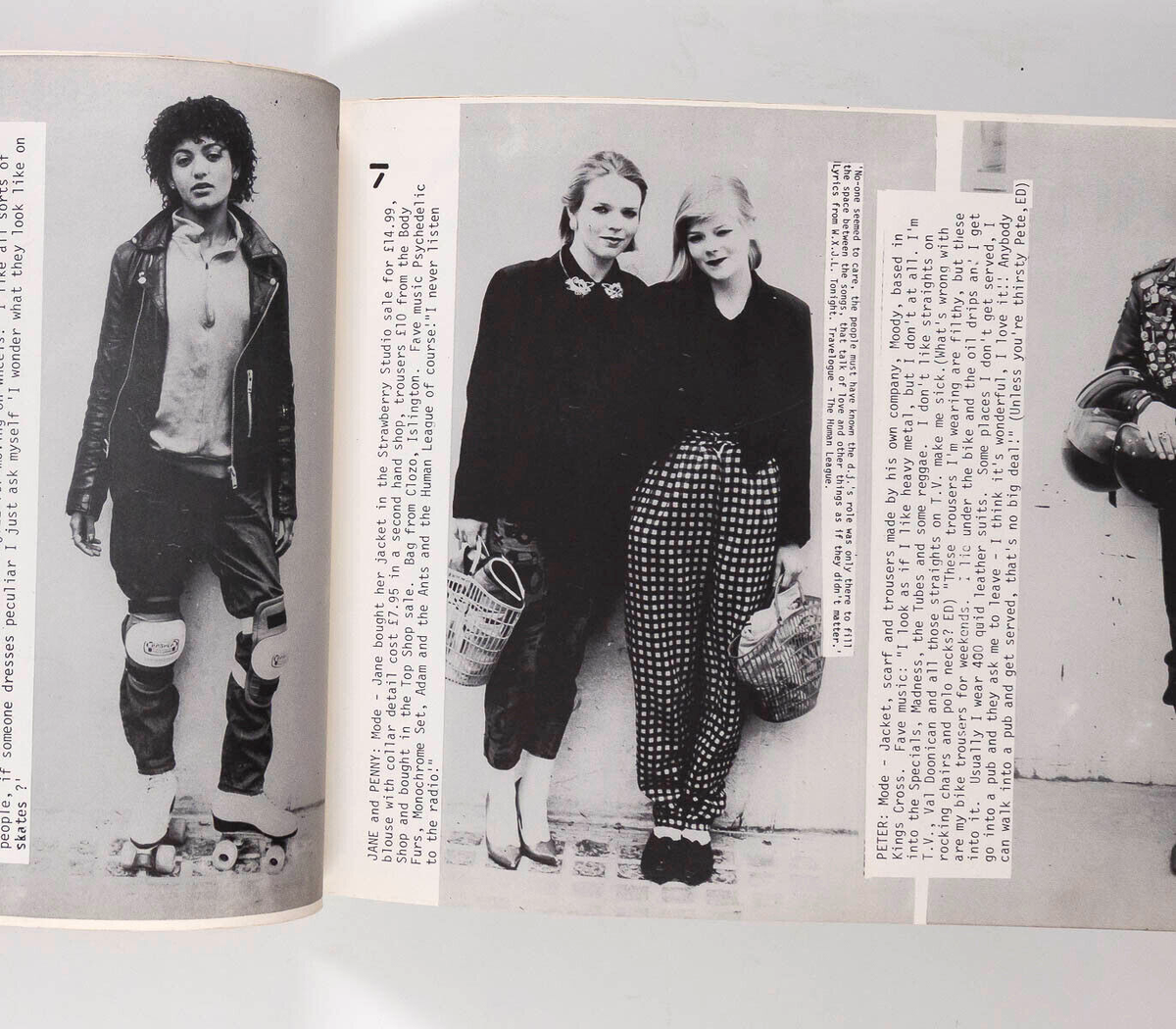

If Sassy, Bitch, and Adbusters established frameworks for critical media engagement, British publications i-D and The Face were doing something equally radical: treating fashion itself as a legitimate mode of cultural analysis. Terry Jones, the former British Vogue art director who founded i-D in August 1980, had submitted a proposal for street-style photography to Vogue in 1977. They rejected it as "too revolutionary." Three years later, he was selling hand-stapled photocopied fanzines out of King's Road boutiques and Rough Trade record stores. The first run moved fifty copies at 50p each.

Jones's innovation was the "straight-up"—full head-to-toe portraits of street-cast individuals photographed against plain walls. He'd been inspired by August Sander's social documentary portraits and Irving Penn's Small Trade series, but the application was new. Instead of photographing fashion on professional models, i-D documented what actual people were wearing on actual streets. The message was ideological: fashion wasn't something dictated from runways but something that emerged from subcultures, from punks and New Romantics and club kids inventing themselves nightly.

"Style isn't what but how you wear clothes," Jones declared. "Fashion is the way you walk, talk, dance, and prance." Every i-D cover featured the subject winking—when turned sideways, the letters i-D form a winking face. But the wink also represented the magazine's core philosophy: there are always two sides to a story, you can't judge someone on face value.

Across town, Nick Logan launched The Face the same year with £3,500 in personal savings. Logan had edited NME during its 1970s heyday and created Smash Hits, but The Face was something new—Britain's first magazine to present youth culture as an integrated system where music, fashion, art, and politics all collided. When Neville Brody joined as art director in 1981, he created a visual language drawing on punk, Dadaism, Bauhaus, and Constructivism—typography as ideology, explicitly channeling anti-corporate, anti-establishment movements.

What made these magazines legendary wasn't just aesthetic innovation but talent development. Edward Enninful was spotted on a train at sixteen by stylist Simon Foxton, modeled for i-D, assisted at seventeen, and became fashion director at eighteen—the youngest ever at an international publication. Wolfgang Tillmans, Mario Testino, Terry Richardson, Craig McDean, Nick Knight, Juergen Teller—the photographers who defined contemporary fashion imagery all came through i-D's pages.

These publications shared a conviction that fashion was a legitimate lens for understanding culture—not a superficial distraction from serious matters but a serious matter itself. They covered Thatcher-era politics, the AIDS crisis, drug culture, and activist causes. They documented subcultures with the seriousness anthropologists brought to indigenous communities. They treated their readers as co-conspirators in a cultural project rather than passive consumers of trend information.

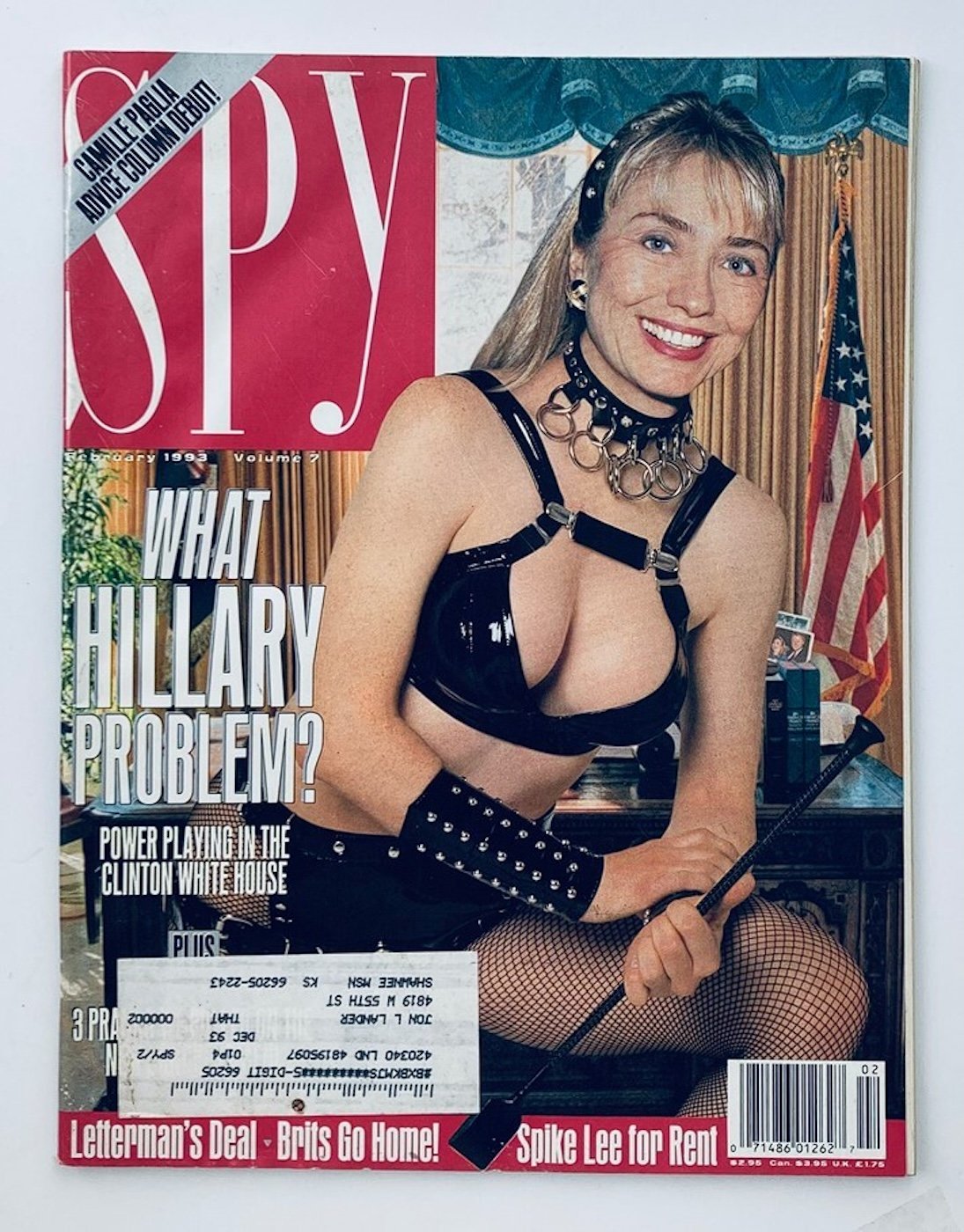

Spy: satire backed by receipts (1986-1998)

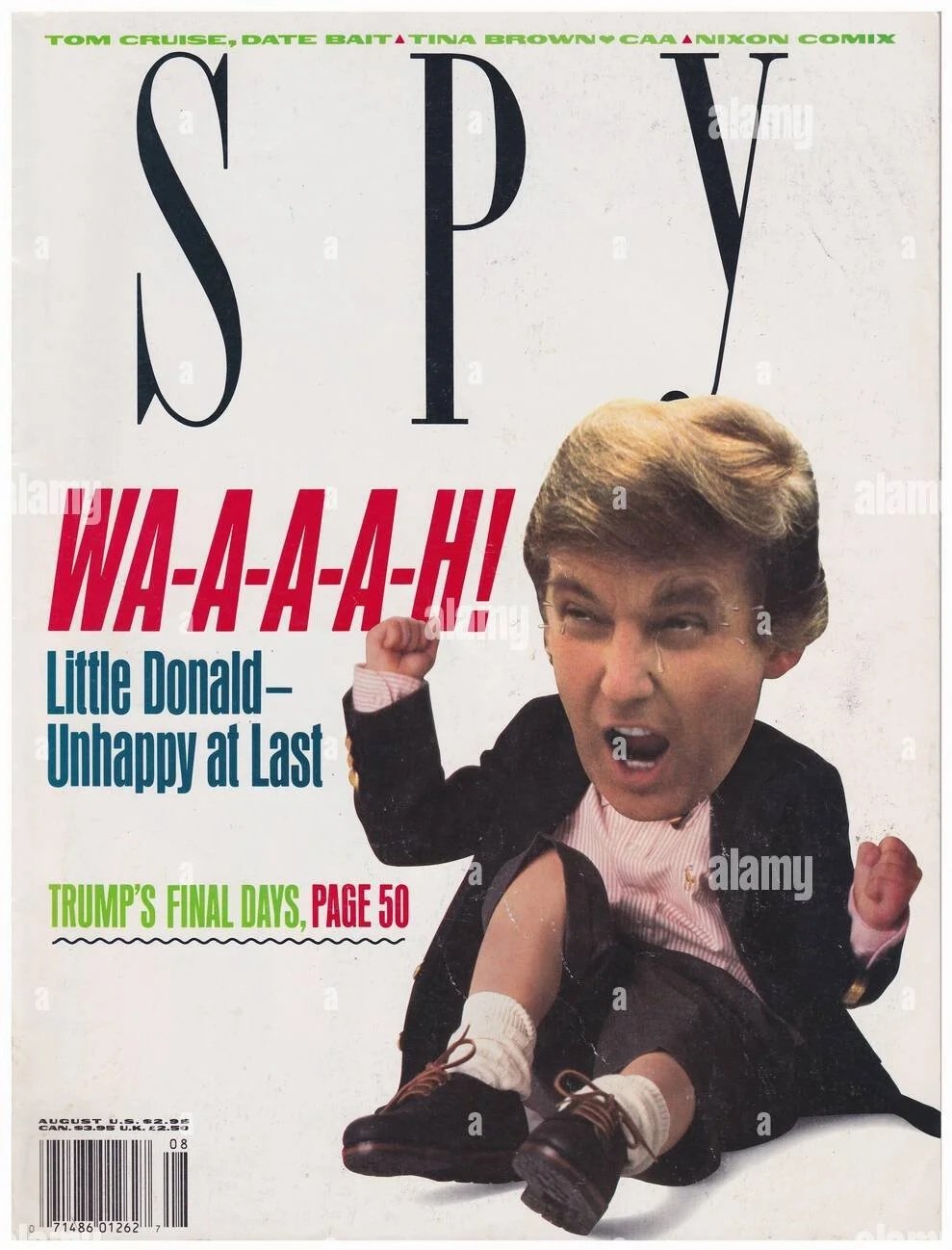

While i-D was documenting British street style in London and Adbusters was culture-jamming capitalism in Vancouver, Spy Magazine was doing something equally revolutionary in New York: proving that vicious satire could be backed by rigorous investigative journalism.

Founded in 1986 by Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter (both refugees from Time magazine), Spy positioned itself with a motto that became legendary: "Smart. Fun. Funny. Fearless." The target was clear: New York's media elite, Hollywood celebrities, and the wealthy powerful who thought themselves unaccountable. Donald Trump became the magazine's signature punching bag, immortalized as a "short-fingered vulgarian" in epithets that stuck for decades.

But here's what separated Spy from mere snark: every barbed joke was backed by painstaking reporting. Journalism professor Kevin M. Lerner wrote that Spy "invented the painstakingly reported – but still funny – satirical magazine feature." When they mocked Arnold Schwarzenegger or exposed Donald Trump's financial wobbles, the mockery rested on documented facts. The satire wasn't mean for entertainment—it was accountability journalism dressed in elegant cruelty.

Dave Eggers called it "the most influential magazine of the 1980s...cruel, brilliant, beautifully written and perfectly designed, and feared by all." That combination mattered: the design was sophisticated (inspired by 16th-century polyglot bibles and 1920s type specimens), the writing was sharp, and the research was solid. It looked like a comedian performing in a tuxedo—the formal presentation made the viciousness land harder.

Spy pioneered what Open Culture called "class-rage" journalism, combining investigative rigor with healthy contempt for pretension. In 1990, they sent checks for $1.11 to wealthy celebrities including Rupert Murdoch to see who would bother cashing them. (Murdoch cashed his immediately. Donald Trump cashed his too.) The stunt was funny, but it made a point about greed that straight reporting couldn't capture as effectively.

The magazine reached 200,000 circulation and influenced a generation of journalists who learned, as Lerner noted, that "the Spy attitude" could be "ingrained not just into their writing but into their world view." When Gawker launched in 2003, founder Elizabeth Spiers explicitly cited Spy as inspiration, carrying back issues for reference. The snarky, fact-based accountability journalism of digital media traces directly to Spy's legacy.

Spy sold to new owners in 1991, struggled financially despite breaking even, and ceased publication in 1998. But its model survived: elegant presentation + vicious satire + rigorous facts = journalism that holds power accountable while remaining compulsively readable. In hindsight, Spy was doing what Teen Vogue would later do—taking readers seriously enough to give them both entertainment and substance, refusing to separate style from politics, treating fashion and culture coverage as opportunities for accountability journalism.

The forty-five-page deck that changed everything

When Phillip Picardi interviewed for the digital editorial director position at Teen Vogue in 2015, he brought a forty-five-page presentation arguing that the magazine was underestimating its audience. He'd worked at Refinery29 under Mikki Halpin, whose influence had sparked his interest in political engagement. He was openly gay, twenty-four years old, and convinced that the teenage girls reading Teen Vogue could "do a TikTok dance and fully understand foreign policy. Those things are not mutually exclusive."

He got the job. Within months, Teen Vogue went from publishing ten to fifteen stories daily to fifty to seventy. Traffic increased 500% in two years. And the content changed. Picardi pushed for coverage of women's rights, race relations, reproductive rights, identity politics. When the site published a critical Nancy Reagan obituary in March 2016—condemning her lack of action on AIDS—hate mail flooded Condé Nast executives. Elton John's AIDS Foundation sent a letter of support.

The magazine covered Standing Rock by interviewing teenagers from the Sioux tribe. It ran a trans healthcare series featuring conversations between model Hari Nef and singer Troye Sivan. It published articles on epigenetics and intergenerational trauma that treated teenage readers as capable of processing complex biological and historical concepts. Kim Kelly's "No Class" labor column made Teen Vogue one of the best sources for union coverage in American media, reporting on Amazon warehouse conditions and wildcat strikes with the same care the magazine brought to streetwear trends.

When Elaine Welteroth became editor-in-chief in 2016 at twenty-nine—the youngest in Condé Nast's 107-year history and only the second Black person to hold the title—she brought sensibilities from her time at Ebony Magazine, where she'd learned how to "lift up the underdog and be the underdog." The publication that had emerged from Sassy's DNA, filtered through Bitch's pop culture feminism, was now doing something unprecedented: combining all of it with mainstream reach.

The Tucker Carlson confrontation crystallized the moment. When Lauren Duca appeared on his Fox News show in December 2016 after her viral "Gaslighting" essay, Carlson told her: "You should stick to the thigh-high boots, you're better at that." Duca fired back: "You're actually being a partisan hack who is attacking me ad nauseam and not even allowing me to speak." She named her column "Thigh-High Politics" in response, selling t-shirts that read "I like my politics thigh-high" with proceeds going to Planned Parenthood—in Tucker Carlson's name.

The exchange encapsulated what Teen Vogue had become: a magazine that refused to accept the premise that fashion and politics occupied separate categories, that caring about appearance disqualified anyone from serious thought. Subscriptions increased 535% year-over-year. By 2017, the politics section had surpassed entertainment as the site's most-read section.

The economics of erasure

On November 2, 2017, Condé Nast announced Teen Vogue's print edition would cease after the December issue. Single-copy sales had dropped 50% in the first half of 2016. The same month Teen Vogue was proving that young women cared about politics, the advertising model that sustained fashion magazines was collapsing entirely.

The numbers are stark. Periodical publishing revenue fell from $40.2 billion in 2002 to $23.9 billion in 2020—a 40.5% decline. Print magazine advertising specifically crashed from $20.6 billion in 2012 to a projected $6.6 billion by 2024. Meanwhile, internet advertising tripled from $49.3 billion (2013) to $160 billion (2020), with Google and Facebook capturing 60% of the entire digital ad market.

Self ceased print in February 2016. Teen Vogue followed in 2017. Seventeen ended print in 2018. After eighty years of continuous publication, Glamour went digital-only in January 2019. InStyle published its final print issue in April 2022. Bitch Magazine—which had survived as a reader-supported nonprofit for 26 years—finally ceased operations in June 2022. By 2022, no major U.S. monthly women's fashion magazine published twelve times yearly anymore.

The cruel irony: this happened during the #MeToo moment when women's magazines should have been culturally essential. Glamour's Women of the Year franchise had maximum relevance precisely when the publication ceased to exist in physical form. Teen Vogue was producing "a charmingly unholy, strangely coherent mix of explainers on Karl Marx, op-eds calling for prison abolition, and on-the-ground protest coverage from teens" when its pages disappeared from grocery store checkout lines.

On November 3, 2025, Teen Vogue's website was folded into Vogue.com entirely. The politics editor was laid off along with most remaining staff. Condé United, the company union, condemned the merger as "clearly designed to blunt the award-winning magazine's insightful journalism at a time when it is needed the most."

The pattern repeated across the industry. Paper Magazine laid off staff and ceased editorial operations in April 2023. i-D was sold to Vice, then to Karlie Kloss's Bedford Media after Vice's bankruptcy. The publications that proved audiences were intelligent enough to handle cultural criticism wrapped in entertainment packaging—they all died anyway.

What was actually lost

Here's what Adbusters understood that the advertising industry tried to ignore: all media messages are political. There's no neutral ground. A fashion magazine that only covers trends without analyzing why those trends emerge, who profits from them, what labor conditions produce them—that magazine isn't apolitical. It's just endorsing the status quo by pretending alternatives don't exist.

Sassy, Bitch, Teen Vogue, i-D, Adbusters—they all rejected that pretense. They insisted that treating audiences as thoughtful people capable of complex analysis wasn't a niche strategy but the only ethical approach. They proved it could work commercially (until economic forces beyond editorial control killed them anyway).

What migrated to Substack—newsletters like Amy Odell's "Back Row," Leandra Medine Cohen's "The Cereal Aisle"—couldn't replicate what magazines offered. Newsletters provide independent voice and freedom from advertiser pressure, but they lack institutional fact-checking resources, photography budgets for major shoots, entry-level positions for young journalists, and reach to readers who don't subscribe to newsletters.

The physical magazine—present at checkout lines, visible in waiting rooms, passed between friends—was a delivery mechanism for ideas that reached audiences who would never seek out political commentary directly. Teen Vogue's peculiar alchemy—progressive politics wrapped in glossy fashion packaging, delivered to teenage girls at grocery stores—cannot be replicated digitally.

The Korean gap: where critical fashion journalism goes to die

It’s a pretty picture, but — YAWN.

Every major fashion publication that understood fashion as cultural criticism rather than consumerism emerged from specific subcultural moments: Sassy from American feminist consciousness, Bitch from third-wave pop culture analysis, i-D and The Face from British post-punk, Adbusters from anti-consumerist activism. Each reflected its culture's particular tensions between individual expression and social conformity, between commercial fashion and authentic style.

Korean fashion has undergone a transformation at least as significant as any of these historical moments—but without the critical media infrastructure to document it. And that absence isn't accidental.

A 2009 Korean textbook on fashion journalism stated the problem plainly: Korea's "fashion market is world-class, and the awareness and level of fashion journalism is low." Fifteen years later, that assessment remains accurate. Korean fashion magazines—Vogue Korea, Elle Korea, Harper's Bazaar Korea, W Korea, Marie Claire Korea—are almost exclusively licensed editions of Western titles, operating under corporate mandates that prioritize commercial relationships over critical analysis.

The editorial photography tells the story. Korean fashion photographer Oh Se Ae, who shoots for Vogue Korea and GQ, describes loving to "work with friends who are interested in doing something that isn't so commercial"—the implication being that most Korean fashion editorial work IS commercial, prioritizing brand relationships and safe aesthetics over experimentation. Unlike i-D's street-cast portraits or The Face's provocative cultural commentary, Korean fashion magazines produce glossy, conventional editorials that could appear in any market worldwide. The photography is technically proficient and aesthetically safe. Soft focus. Flattering light. Everything pretty, nothing challenging. It sells products. It doesn't challenge anything.

This is where visual methodology becomes political. Soft-focus photography isn't just an aesthetic choice—it's an ideological one. It flatters. It conceals. It makes everything palatable. The gentle lighting says: don't worry, fashion is just beautiful things for beautiful people. Nothing complicated here. Nothing that requires thinking.

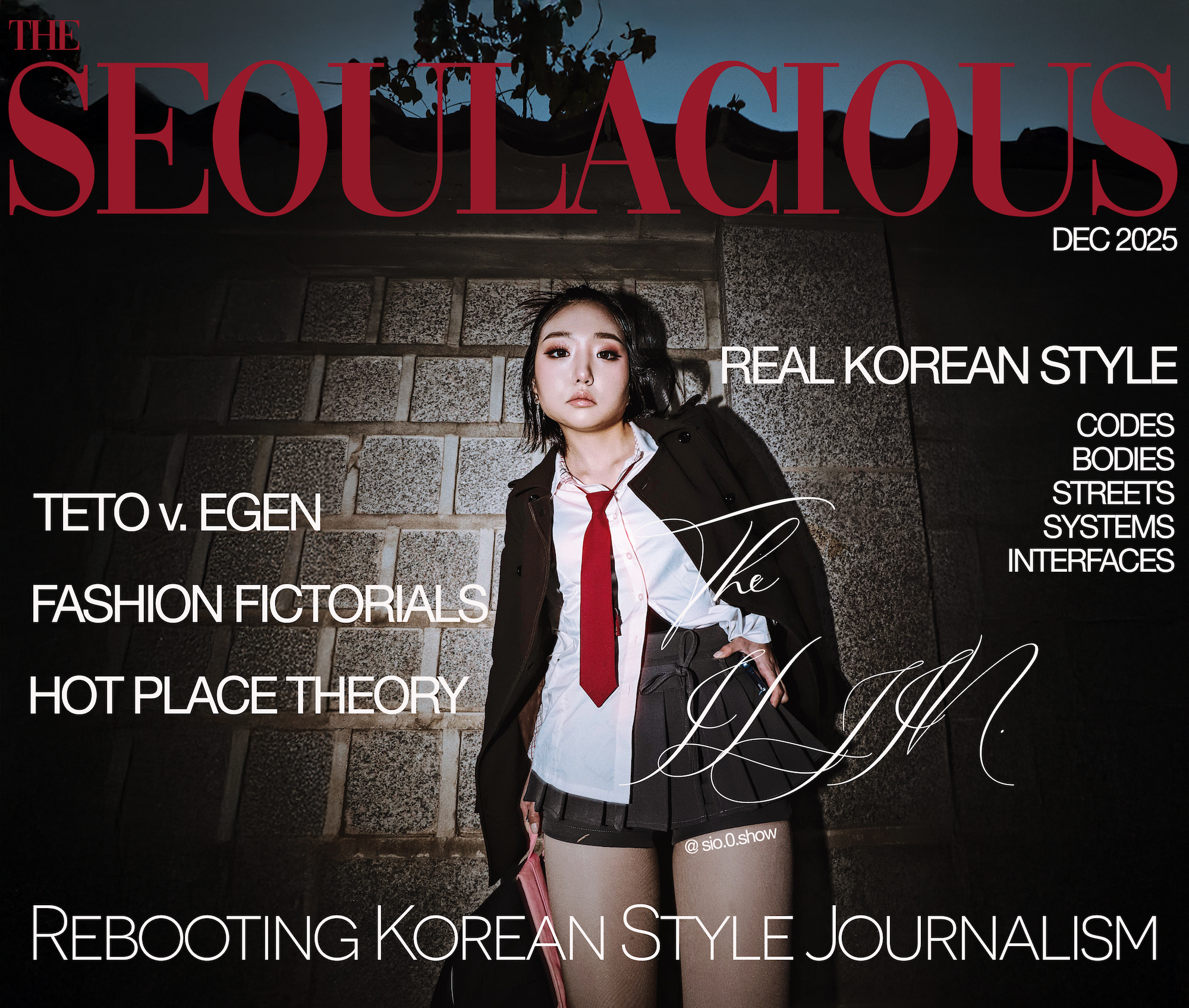

SEOULACIOUS rejects that entirely. When we photograph pretty things—and Korean fashion produces genuinely beautiful work—we light them hard and stark. Flash photography that shows everything. No soft focus to blur the details. No gentle rim lighting to make subjects glow angelically. We use the harsh, unflinching lighting that reveals texture, shows imperfection, captures reality. Our raw aesthetic doesn't pull punches visually any more than we pull punches editorially.

This isn't accident. It's methodology. Hard light = hard truth. If we're going to critique consumerism, we can't always photograph products like luxury advertisements. If we're going to analyze Korean beauty standards, we can't only use the same flattering techniques that create those standards. If we're claiming to do journalism rather than promotion, our images need to look more like documentation, not mere items of commercial aspiration.

More revealing: the Korean fashion establishment actively questioned the legitimacy of street style documentation. In 2007, when I, as Korea’s first professional street fashion photgrapher cover Korean stret fashion with press credentials, began documenting the stylish attendees outside Seoul Fashion Week—young Koreans wearing neon stockings, experimental makeup, and innovative combinations from Dongdaemun's no-brand retailers—officials questioned why I was "wasting time outside" photographing "just... normal people" in the lines who "have nothing to say about fashion."

The "real fashion," they insisted, was inside the shows. On the runways. In the official presentations. Not in the parking lot where teenagers were creating visual languages that didn't exist in fashion textbooks, constructing identities through clothing in ways traditional fashion theory couldn't describe. This attitude revealed what Korean fashion media considered legitimate: official, sanctioned, commercially viable content. Not cultural analysis. Not critical engagement. Not documentation of how actual Koreans were using fashion to negotiate identity in a rapidly transforming society.

The MZ generation now embraces individualism under the banner of "내 멋대로" ("I do it my way"), challenging societal norms in a culture historically defined by collective conformity. Korean designers gain international recognition. Seoul Fashion Week attracts global buyers. K-pop makes Korean aesthetics influential worldwide. But where is the Korean Bitch Magazine interrogating what these fashion trends reveal about gender politics? Where is the Korean Adbusters culture-jamming the consumerism driving Korea's beauty industry? Where is the Korean i-D treating street style as anthropological data rather than trend-spotting?

The answer: nowhere. Only the conventional western outlets of fashion journalism got a Korean version. Korean fashion media overwhelmingly reproduces the safe, commercial model that Western alternative publications spent decades rejecting. Critical fashion journalism—asking what fashion choices mean, how they reflect Korean social tensions, why certain aesthetics emerge from particular cultural moments—barely exists in Korean or English.

Why a SEOULACIOUS mode is the thing now

This how WE rollin.’ With ajummodels (@ajummodel), stark photography, and strong subjects.

What would it mean to create a magazine that combines:

Sassy's refusal to condescend to readers

Bitch's feminist pop culture analysis

Adbusters' culture-jamming critique of consumerism

i-D's conviction that street style is cultural theory

Teen Vogue's political directness

…but focused on Korean fashion and culture?

It would mean treating Korean fashion not as an export product to be marketed globally but as a cultural system to be analyzed critically. It would mean covering the labor conditions in Korean garment manufacturing alongside the runway shows. It would mean documenting the tension between K-pop's manufactured aesthetics and the individualism Korean youth actually practice on streets. It would mean asking why certain silhouettes dominate Korean fashion, what social pressures shape beauty standards, how economic precarity influences clothing choices.

It would mean assuming readers are intelligent people who care about Korea, about fashion, about politics, about culture—and who don't want these topics artificially separated.

It would mean understanding that all fashion coverage is political. A magazine that documents Seoul Fashion Week without analyzing who gets access, whose aesthetics get valorized, what class positions enable participation—that magazine isn't neutral. It's just pretending alternatives don't exist.

But SEOULACIOUS does something else critical that existing Korean fashion media fails at entirely: we export Korean cultural intelligence to the world.

Korean soft power has conquered global markets through K-pop, K-dramas, and K-beauty. Korea's government invests billions in promoting Korean culture internationally. But fashion journalism—actual critical engagement with Korean style as cultural production—remains trapped in Korean-language publications with no international reach, or licensed Western magazine editions that treat Korea as just another market for luxury brands.

SEOULACIOUS writes in English. We analyze Korean fashion and culture for both Korean readers who want serious engagement with their own society and international audiences who recognize that Korea's cultural innovations deserve the same analytical depth Western media lavishes on Paris, London, or New York. We're cultural translators in both directions: explaining Korean fashion's significance to global readers while importing critical methodologies Korean fashion media lacks.

This is nation branding, but honest. Not promotional puffery about Korean excellence. Not tourism board platitudes about traditional hanbok. Real analysis of how Korean society produces fashion innovation, what tensions drive aesthetic evolution, why Korean style matters as cultural expression. We make Korean fashion intellectually interesting to people who don't give a damn about shopping.

The gap is obvious. The historical examples prove such publications can be culturally transformative. Sassy readers define their adolescence as "pre-Sassy and post-Sassy." Spy Magazine influenced an entire generation of journalists who embedded its attitude into their worldview. Bitch Magazine created an entire generation of feminist media critics. i-D alumni dominate global fashion media. Adbusters helped launch Occupy Wall Street. Teen Vogue's political coverage reached millions of young women who might never have engaged with traditional political journalism.

SEOULACIOUS carries this torch not out of nostalgia but necessity. The publications that proved young people deserve serious treatment—the magazines that assumed intelligence rather than pandering to stereotypes—mostly died. What remains is the principle they established and the gap they revealed.

Someone has to do edgy, critical Korean fashion journalism. Someone has to treat Korean readers and Korea-interested global audiences as sophisticated cultural participants rather than consumers awaiting trend instructions. Someone has to bring Spy Magazine's accountability journalism and class-rage critique to Korean elites. Someone has to culture-jam the consumerist coverage that currently dominates Korean fashion media. Someone has to apply Bitch Magazine's pop culture feminism and Adbusters' anti-consumerist critique to the Korean context. Someone has to document Korean street style with i-D's anthropological rigor and analyze it with Teen Vogue's political directness.

And someone has to do it in English, making Korean fashion culture accessible to the world while maintaining the critical rigor that makes the analysis worth reading. That's cultural export with actual value—not just selling Korea, but making Korea intellectually essential.

But here's what separates SEOULACIOUS from every well-intentioned attempt at "critical fashion journalism" that still looks like a luxury brand lookbook: our visual language matches our editorial stance. We photograph Korean fashion with hard light and stark compositions that show everything—the texture, the construction, the reality. No soft focus to make everything dreamy and aspirational. No gentle rim lighting to create halo effects. Flash photography that reveals rather than flatters. Raw aesthetics that refuse to pull punches visually the way we refuse to pull punches editorially.

This matters because photography is ideology made visible. When Korean fashion magazines shoot editorials with soft, flattering light, they're not just making aesthetic choices—they're making political ones. That gentle glow says: fashion is beautiful, consumption is pleasure, don't think too hard about any of this. The pretty picture conceals the labor conditions, the environmental costs, the social pressures, the economic structures. Soft focus = soft criticism = no criticism.

Our first monthly “cover”, for the month of December 2025.

SEOULACIOUS lights things the way Adbusters photographed consumption—honestly, starkly, showing the thing itself rather than an idealized fantasy version. When we shoot garter stockings in Hongdae or wrinkle socks in Sadang, we're not creating aspirational lifestyle imagery. We're documenting cultural phenomena with the same unflinching directness we bring to analyzing what those phenomena mean. The hard light matches the hard questions. The raw aesthetic reflects our refusal to make Korean fashion prettier or simpler or safer than it actually is.

The fashion magazine didn't just die. It was upgraded, and then killed anyway. But the upgrade survived the death. The experiments in taking readers seriously, in treating fashion as culture, in refusing to separate style from substance—that all continues. It continues in independent publications that rejected corporate funding. It continues in culture-jamming activists who use advertising's weapons against itself. It continues in feminist critics who refuse to separate pleasure from analysis.

It continues in Seoul—where it's needed most and exists least.

Korea's fashion media landscape is dominated by safe, commercial content that serves brand relationships over cultural analysis. But Korea's cultural innovations deserve the analytical treatment Western media gives to Paris and London. Korean youth creating visual languages through fashion deserve the anthropological seriousness i-D brought to British subcultures. Korean social tensions expressed through style choices deserve the feminist critique Bitch applied to American pop culture. Korea's elite power structures deserve the accountability journalism and class-rage Spy brought to New York's wealthy. Korea's consumerist pressures deserve the culture-jamming resistance Adbusters deployed against advertising. And Korean fashion deserves to be photographed the way it actually exists—with a lot of hard light that shows the texture and reality, not just soft focus Vaseline-on-the-lens filters that turns everything into aspirational,Disney fantasy.

SEOULACIOUS exports Korean cultural intelligence through serious English-language journalism backed by visual methodology that refuses to flatter. We light Korean fashion the way we analyze it: directly, honestly, showing everything rather than concealing anything. Hard light. Hard questions. No soft focus. No pulled punches. We shoot at f16, at least. This raw, inclusive aesthetic isn't just our style—it's our ethics made visible.

The question was never whether young people cared about politics and culture alongside fashion. The question was whether anyone would bother to ask. The question was never whether Korean fashion warranted critical analysis. The question was whether anyone would provide it. The question was never whether international audiences wanted sophisticated engagement with Korean culture. The question was whether anyone would deliver it in accessible English.

SEOULACIOUS asks—and assumes the answer is yes.