"The Hungry Profession": Inside Korea's Senior Modeling Money Machine

Even the Celebrity Success Story Can't Make Rent

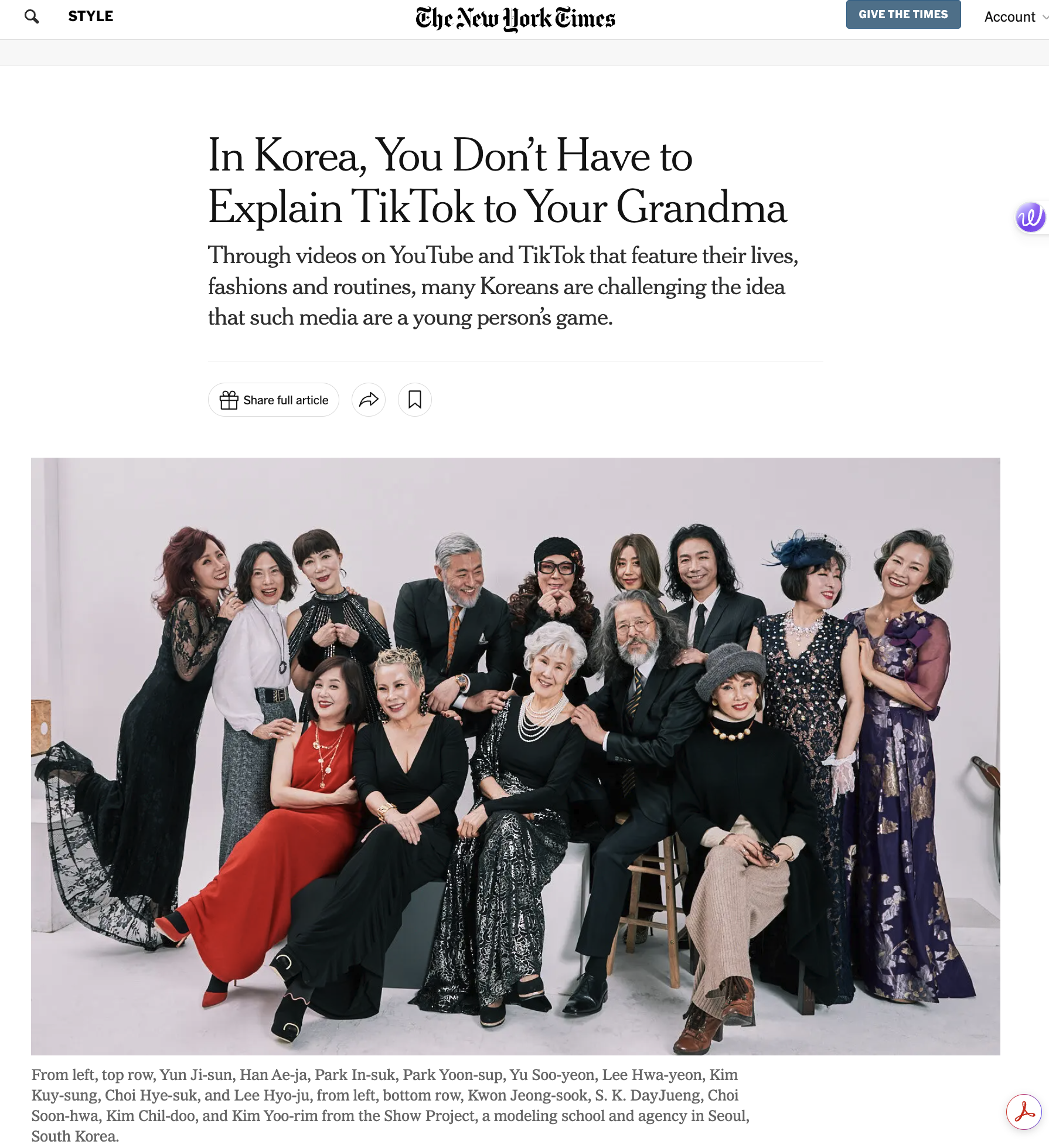

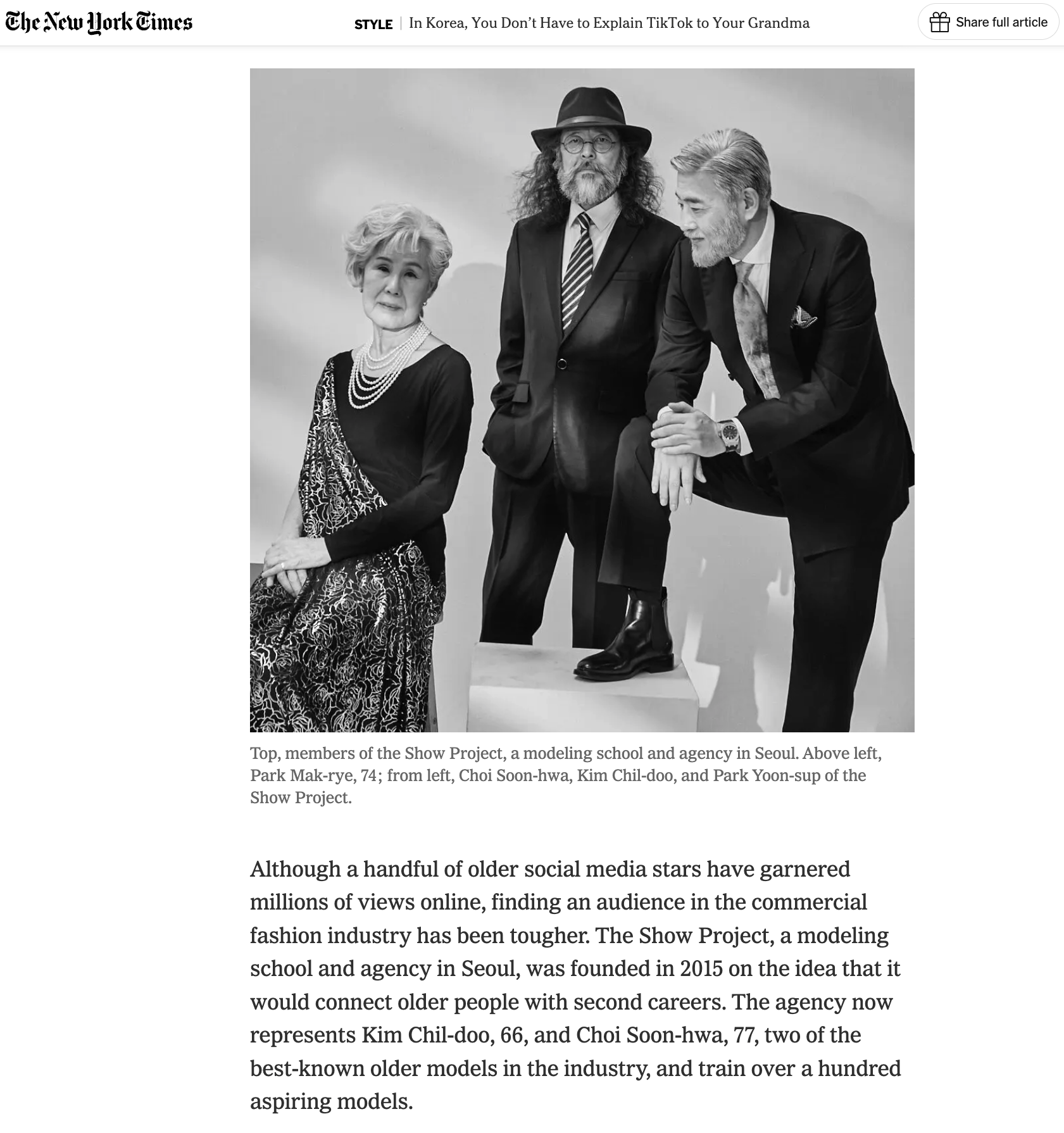

Kim Chil-doo walked Seoul Fashion Week at 64. The New York Times profiled him. He became the international face of Korean senior modeling. And he just went on TV to say he's looking for work as a taxi driver because modeling doesn't pay enough to eat.

Let that sink in for a moment. Korea's most famous senior model—the one success story the industry points to again and again—appeared on MBN's 특종세상 and told the nation: "일이 있을 땐 있고 없으면 먹고살 게 없다" (When there's work, there's work, but when there isn't, there's nothing to live on). He called modeling a "배고픈 직업"—a hungry profession. This from a man who's walked runways internationally, been featured in major ad campaigns, achieved everything the industry promises as possible.

If Kim Chil-doo can't make senior modeling financially viable, what's happening to the thousand-plus people who've graduated from modeling academies expecting their "second act"?

In August 2020, Korea Textile News—an industry publication, not some outside critic—published an editorial with a question so blunt it could've been a weapon: "시니어모델 지망생들은 '열린 지갑'인가?" Are senior model hopefuls just "open wallets"?

Turns out they were onto something.

The Math Ain't Mathing

Here's what it costs to become a senior model in Korea:

Year One Investment:

Training program (Chungang University's full curriculum): ₩3.6 million ($2,700)

Professional portfolio photography: ₩300,000

Competition entry fees (three contests): ₩300,000

Hair and makeup for events: ₩250,000

Wardrobe purchases: ₩500,000

Total outlay: ₩4.95 million (roughly $3,700)

Expected first-year income for most participants: ₩0.

Best-case scenario if you're exceptionally lucky and land a few minor jobs: ₩200,000-500,000.

The Korea Textile News editorial laid it out: training academies and competitions are proliferating "우후죽순"—like mushrooms after rain. But the actual work? That's going almost exclusively to the same handful of celebrity seniors who already had decades-long careers before "transitioning" to senior modeling. Everyone else is paying to participate.

When "No Fee" Is Actually the Fee Structure

Listen to what actual participants say when asked about income:

"수입은 거의 없어요. 자아실현이라 할 수 있지요" (Income is almost zero. You could call it self-actualization) - testimonial from Senior Times investigation

"수입은 전혀 없어요. 오히려 참가비 등을 내고 무대에 서고 있어요" (There's absolutely no income. Rather, we PAY participation fees to stand on stage) - another Senior Times interview

One five-year veteran of the senior modeling circuit described it to Seoul Kyungje as "마약" (drugs): "너무 돈이 많이 들어서 안 하고 싶은데 안 하면 몸살이 나" (It costs so much money I want to quit, but if I stop I get withdrawal symptoms).

Think about that phrasing. Addiction. To something that's actively costing you money.

Here's how perverse the economics get: some senior models are required to purchase the clothes they walk in during runway shows. Korea Textile News reported that academies must pay designers "debut fees" just to let their trainees walk in shows, and that "노개런티" (no payment) work is normalized as standard industry practice. The editorial described the quality of many senior fashion shows as "학예회 수준"—elementary school talent show level.

So you're paying to enter a show. Paying for hair and makeup. Sometimes paying for the clothes. Walking a runway that insiders compare to a middle school production. And receiving exactly zero compensation.

This isn't a career. This is paying for stage time.

The Dropout Rate Tells the Real Story

NewSeniorLife, a social enterprise that's operated for a decade in this space, provides the clearest data on actual outcomes. Over ten years, they trained more than 1,400 seniors. Currently, 120 remain as active member-models—an 8.6% retention rate.

And here's the kicker: even among those 120 who stuck with it, exactly zero receive salaries. All work freelance. All have sporadic income. The CEO of NewSeniorLife admitted to Yongin Ilbo: "마음 같아서는 120명의 모델을 모두 직원으로 채용해 월급을 주고 싶지만, 10명도 버거운 현실" (I'd love to employ all 120 as salaried staff, but even supporting 10 is difficult in reality).

When even the organization trying to create a sustainable senior modeling ecosystem admits they can't financially support their own models, what does that tell you about the industry's viability?

Competition numbers paint the same picture of oversupply: the LA Korean Silver Fashion Show received 600+ applicants for 70 spots. That's nearly a 10:1 ratio competing for unpaid runway time.

Who's Actually Making Money Here?

Not the models. So where's the money going?

The business model breaks down roughly as follows:

60-70% of industry revenue: training and education fees

15-20%: competition entry fees

10-15%: portfolio and photography services

Under 5%: actual modeling placement commissions

At least 10-15 entities now operate as dedicated senior modeling agencies or training academies. Major universities—Chungang, Dongduk Women's, Kyung Hee, Shinhan, Baekseok—have launched formal senior model training programs. Department store culture centers offer introductory courses at ₩180,000-210,000 for ten sessions.

Everyone's building infrastructure to train seniors. Almost nobody's building actual pathways to paid work.

Korea Textile News called it directly: the industry shows "비싼 교육비를 받아 챙기는 상술로 번질 기미를 보이고 있다" (signs of becoming commercial exploitation charging expensive tuition), with concern about "시니어들의 허영심을 부추겨 새로운 사회문제가 될 것" (exploiting seniors' vanity becoming a new social problem).

Senior Sinmun was even blunter in their investigation, warning that the industry operates with "장삿속" (commercial cunning) targeting seniors.

How Did We Get Here?

Korea became a "super-aged society" in December 2024—20% of the population is now 65 or older. The nation has the world's lowest fertility rate (0.72 in 2023) and is aging faster than any society in human history, transitioning from "aged" to "super-aged" in just seven years. By 2045, Korea is projected to have the world's highest elderly proportion at 37-46%.

Simultaneously, Korea has the world's most intense "외모지상주의" (lookism) culture—31% of Korean women in their 30s have had plastic surgery, the highest rate globally. Resume headshots are mandatory. There's a common saying: "외모가 반이다" (good looks are worth half).

Then you've got the baby boom generation (born 1955-1963) hitting retirement age starting in 2020. This cohort experienced Korea's rapid industrialization, accumulated significant wealth, and has completely different expectations about retirement than their parents did. The "액티브 시니어" (Active Senior) market is projected to hit 168 trillion won ($125+ billion) by 2030.

So you have: a massive aging population + extreme appearance obsession + wealthy retirees seeking meaning + marketing logic that says "we need age-appropriate models."

What you get is enormous supply (seniors with disposable income seeking validation and purpose) meeting extremely limited demand (brands still overwhelmingly prefer young models). Into that gap has rushed a modeling industrial complex that makes its money on dreams, not placements.

The Media Keeps Selling the Same Fairy Tale

Korean media coverage of senior modeling follows a relentlessly inspirational script: "인생 2막" (second act) narratives, transformation stories, counter-ageism messaging. They profile the same handful of success stories over and over—Kim Chil-doo, So Eun-young, Choi Soon-hwa—while rarely examining the economics.

They emphasize family support, health benefits, emotional fulfillment. They don't talk about dropout rates. They don't calculate return on investment. They definitely don't mention that even the celebrity faces of the movement can't pay their bills.

A 2018 academic study found senior models appeared in only 10.53% of magazine advertisements—and 40.8% of those appearances were for pharmaceutical and medical products. The fashion industry hasn't actually expanded its appetite for older faces. It's just found a new demographic willing to pay for the fantasy of walking runways.

What This Actually Is

Look, there are legitimate benefits to senior modeling programs. They combat isolation. They provide structured social activity. The posture and movement training has real health benefits. For seniors with disposable income who understand they're essentially paying for a hobby—like golf or pottery classes—this can be worthwhile.

But that's not how it's being sold.

It's being sold as career transition. As a viable "second act." As financial opportunity. The marketing language is all about professional development, representation in the industry, breaking into fashion. The reality is: you're paying to walk in student-quality shows, maybe get some amateur portfolio shots, and be part of a community of other people who are also paying to participate.

NewSeniorLife's data is stark: less than 1% of trainees achieve anything approaching sustainable income from modeling. Even among the 8.6% who stay active, none are salaried employees. They're hobbyists funding their own participation.

The Uncomfortable Truth Korean Media Won't Say

Here's what no Korean media outlet will publish, because they all depend on advertising from these same modeling academies, universities, and competition organizers:

This is a Ponzi scheme structure. Not literally—no one's promising guaranteed returns or recruiting downlines. But functionally, the money flows from aspirants to institutions, while the actual product (modeling work) barely exists. The business model requires constant intake of new paying students to sustain operations, because almost none of the students will generate income that could circle back as placement commissions.

The Korea Textile News editorial ended with this call: "교육, 매니지먼트, 패션 관계자들은 '선의'와 '정도'를 회복해야 한다" (Education, management, and fashion professionals must recover 'good faith' and 'integrity').

That would require fundamentally restructuring how this industry operates. It would mean:

Being transparent about actual employment outcomes

Charging proportional to realistic income potential (i.e., much less)

Creating genuine pathway programs with industry partners

Stop using competition entry fees as revenue streams

Honestly marketing this as expensive hobby activity, not career training

None of that is happening. Instead, university programs are expanding. More competitions launch every year. The infrastructure for extracting fees grows while the actual paid work remains essentially static.

If Kim Chil-doo Can't Make It Work...

Let's return to where we started. Kim Chil-doo has everything the industry claims you need to succeed: distinctive look (181cm tall, striking features), viral breakthrough moment (Seoul Fashion Week 2018), international media coverage (New York Times profile), brand partnerships, runway experience, the whole package.

And he went on national television to say he's seeking taxi driver work because modeling leaves him hungry.

That's not a failure of Kim Chil-doo's effort or talent. That's a market signal about the industry itself. If the absolute best-case scenario—the guy who hit every possible lucky break—still can't achieve financial stability, what does that tell you about the 1,400+ people who've paid for training programs?

Senior Sinmun asked: "시니어 모델? 혹시 장삿속?" (Senior modeling? Or maybe just commercial exploitation?)

The uncomfortable answer: mostly the latter, with just enough of the former to keep the pipeline full.

Korea's seniors deserve better than being treated as "열린 지갑"—open wallets. They deserve honesty about what they're buying: not career training, but expensive access to a community and stage time. That might still be worth it for some. But only if they know what they're actually paying for.

Right now, they're being sold a dream that doesn't pay rent. Just ask Kim Chil-doo.

SEOULACIOUS is the only publication doing critical Korean fashion journalism in any language. We can say what Korean outlets can't because we don't depend on advertising from the institutions we investigate.