The Machine That Eats Neighborhoods Wholesale: How Korean Redevelopment Actually Works

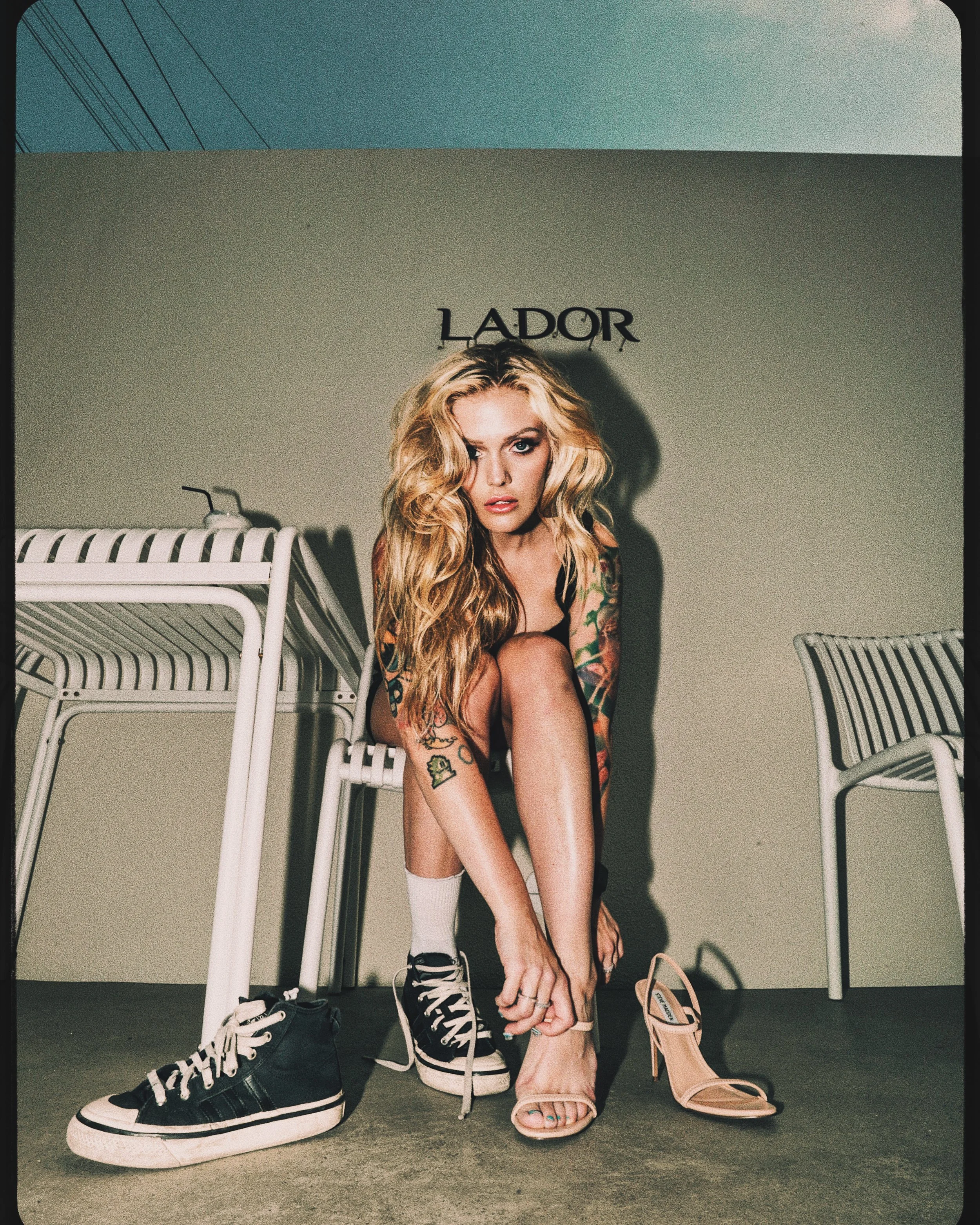

Model @raqulaaa changes modes in the multi-modal space of a Seongsu popup’s coffee shop. This is where myriad urban interfaces collide, merge, and harmnonize into something more compelling.

A SEOULACIOUS Investigation

The Workshops That Know They're Dying

In Seongsu-dong, more than 50 workshops and small studios are currently operating in buildings slated for demolition. Data from the Seongsu 1-dong Community Center documents leather workers, bag makers, small manufacturers—businesses that have occupied the same industrial spaces for 15, 20, 25 years. Most of their owners now know the approximate timeline for when their buildings will come down: sometime between late 2025 and early 2027, depending on which redevelopment zone they fall into.

The workshop owners aren't fighting it. They've seen this happen across Seoul for decades. When the redevelopment approval notices came last October, they did what every small business owner in Seoul does when they hear that word—재개발 (jaegaebal, redevelopment): they started calculating. Not whether to stay, but how much time they had left, and where the hell they would go next.

Model @raqulaaa helps explores some of the desolate industrial spaces that also define Seongsu, with a contrast of hard vs. soft, flesh vs. metal, and human vs. machine aesthetics. It also helps us visually note how maled these industrial spaces are, as well as how powerfully differently gendered objects stand out in this heavily maled space.

What strikes you, talking to multiple shop owners in the district, is how they articulate the same paradox: their neighborhood just became cool. Young people started coming for the cafés, the galleries. Foreign design magazines wrote features about Seongsu's "authentic industrial character." But that's exactly why they have to leave. The very attention that validated their presence made the land beneath their workshops too valuable to let them stay.

This is the central paradox of Korean urban development, and it plays out with mechanical precision across Seoul: the very thing that makes a neighborhood valuable—its character, its small businesses, its existing community—is the first thing that gets demolished when property values rise. And unlike the gradual gentrification you might see in Brooklyn or East London, where some original residents hang on, some businesses adapt, Seoul's redevelopment system is designed to do something much more absolute.

It replaces populations wholesale.

The System You've Never Heard Of

Most foreigners living in Seoul have no idea this system exists. They see the über-cool coffee shops, pop up stores, and boutiques. They might even see the new, name-brand apartment towers going up—those identical beige fortresses that march across the city's skyline—and assume it's just regular real estate development. Build apartments, sell apartments, done.

They're wrong.

What they're witnessing is one of East Asia's most sophisticated systems of urban transformation, a machine that has fundamentally reshaped Korean cities over the past 50 years. It's called 재개발 (jaegaebal—literally "re-development") and its cousin 재건축 (jaegeonchuk—"re-construction"), and together they form the legal and financial architecture for something unprecedented: the periodic, wholesale replacement of urban populations every 30-40 years. The system emerged from 1970s-era development policies under Park Chung-hee's rapid urbanization programs, was formalized through various iterations of the Urban Redevelopment Act, and continues to structure Seoul's transformation today.

This isn't gentrification as Westerners understand it. This is population turnover by design.

Here's how it works: A group of property owners in an aging neighborhood decide they want to demolish everything and build new apartments. They form what's called a 재개발조합 (jaegaebal johap)—a redevelopment association. Under the 도시 및 주거환경정비법 (Dosi mit Jugeo Hwangyeong Jeongbibeop, the Act on the Maintenance and Improvement of Urban Areas and Dwelling Conditions for Residents), if they can get two-thirds of landowners to agree (and in practice, if they can get city approval), they can force the remaining third to participate whether they want to or not. The existing buildings get demolished. Major construction companies build new apartment towers. Units are distributed to original owners based on their land holdings, and the rest are sold commercially to finance the project.

Everyone wins, right?

Except for one small problem: most of the people doing business in the old neighborhood can't afford to stay in the new one.

The Sadang Lesson

To understand how ruthlessly efficient this system is, you need to know the story of Sadang-dong in 1988.

Sadang was a poor neighborhood on Seoul's southern periphery—one of those hillside communities of small houses where working-class families had lived for decades. Then the city decided to build a subway line through it. Property values jumped. A redevelopment association formed. And suddenly, 3,283 households—according to municipal records of the Sadang District 4 Redevelopment Project—found out their homes were being demolished.

Most of them were tenants, not owners. They had no legal stake in the land beneath their homes. The redevelopment plan, as documented in the association's compensation scheme, offered them two choices: a small moving expense payment (930,000 won—about $1,200 at the time), or the right to buy a small apartment unit at market rates in the new development.

Neither option was realistic. The moving payment wasn't enough to find another place in Seoul. The apartment units were priced far beyond what working-class tenants could afford.

So they resisted.

On November 6, 1988, it came to violence. Contemporary news reports documented 800 demolition workers and police facing off against 600 residents and student supporters in pitched street battles that left 20-30 people injured. Media covered it. For a moment, it seemed like the residents might win something—some compromise, some recognition of their right to remain in their own neighborhood.

They didn't.

On August 9, 1989, the final clearance came: city records show 1,500 police officers, 200 city officials, and 600 demolition workers forcibly removed the last 299 structures. By 1993, according to Geukdong Construction Company project documents, the redevelopment was complete: 32 gleaming apartment buildings totaling 4,283 units, standing 15-20 stories tall.

None of the original 3,283 households who were displaced in 1987 lived there anymore.

Academic studies of Seoul's Joint Redevelopment Program projects—including research published in Korean urban planning journals—document approximately 80% population displacement rates in cases like Sadang. Not gradual turnover, but almost complete replacement within a few years. The infrastructure improved dramatically. Property values soared. The neighborhood became middle-class.

And every single person who had lived there before was gone.

The Documentary That Couldn't Be Silenced

If Sadang's violence happened in 1988-1989, an even more brutal displacement was unfolding slightly earlier, in 1986-1988, in Sanggyedong—a neighborhood in northern Seoul comprising approximately 1,500 households (1,000 homeowners, 520 renters, according to documentary records). The government wanted it cleared before the 1988 Seoul Olympics. The shacks and small houses couldn't be seen by foreign guests arriving for the Games.

A young filmmaker named Kim Dong-won went to document what he thought would be a single day of protest. He ended up living with the residents for three years, filming their struggle. The result was Sanggyedong Olympics (상계동 올림픽, Sanggyedong Ollimpik, 1988), now considered Korea's first full-length independent documentary and the prototype of Korean activist video.

The footage is harrowing. Women lying prone beneath construction cranes to stop demolition. Grandmothers staying awake all night with bats to guard against forced evictions. Hired thugs beating resisters with steel pipes, sledgehammering through houses still filled with residents' possessions while police hauled off screaming families. According to the London Korean Film Festival's documentation of the film, four local residents died during the struggle. In November 1986, the final demolition came—160 families, as recorded in the documentary itself, forcibly removed from buildings they still occupied.

The evicted residents were relocated to temporary settlements on Seoul's outskirts. Then came the cruel irony: their new shantytown turned out to be along the planned Olympic torch route. They faced eviction a second time—displaced twice so that Olympic visitors "will not suffer the discomfort of seeing a single poor person in Seoul," as the documentary's closing title acidly noted.

Sanggyedong Olympics premiered in 1988 and was invited to the Berlin International Film Festival's Forum section in 1989 and the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in 1991—the first Korean documentary ever selected for Yamagata. But documenting state violence during military dictatorship came with costs. Kim Dong-won's later work, Repatriation (2004), about North Korean spies imprisoned in South Korea, resulted in what film critics documented as his arrest on camera and investigation under the National Security Law—the film won the Freedom of Expression Award at Sundance 2004 precisely because of these pressures. Making documentaries about Korea's redevelopment violence wasn't just controversial—it could land you under police investigation as a possible North Korean sympathizer.

The Sanggyedong Olympics became more than documentation. It became evidence. The film proved that the violence at Sadang wasn't an isolated incident but part of a systematic pattern. The documentary records that approximately 200 daldongne (달동네, daldongne, hillside slum) areas across Seoul faced similar clearances in preparation for the Olympics. Research on Olympic displacement, cited in analyses of Seoul's 1988 preparations, estimates that approximately one million people were forcibly relocated during the Olympic preparations—wholesale population displacement presented as "urban beautification."

The documentary revealed what Korean urban planning scholarship now acknowledges: the 1988 Olympics established the template for modern Korean redevelopment. Not renovation, not gradual improvement—wholesale clearance and population replacement. The system that demolished Sanggyedong and Sadang in the 1980s is the same system demolishing Seongsu today. The violence may be less visible now, bureaucratized into legal procedures and market forces, but the result remains identical: complete population turnover every generation.

The Seongsu Paradox

Which brings us back to Seongsu-dong in 2025, and why those 50+ workshops are doomed precisely because their neighborhood got cool.

Model @zibi1ooo poses in the middle of a row of print shops on the street where the world-reknowned Cafe Onion sits.

Seongsu became trendy through a process Korean urban researchers term "ladification"—gentrification driven primarily by young women's consumption patterns, a concept developed by visual sociologist Michael Hurt to describe a distinct pattern of neighborhood transformation observed across Seoul since the mid-2010s. Old industrial buildings got converted to cafés with perfect Instagram lighting. Small galleries opened in former warehouses. The neighborhood developed a reputation for being "authentic," "creative," "not-too-commercial."

The world-famous Dior pop up store in Seongsu has become a permanent fixture for which a reservation is absolutely required. As an urban interface, the huge, abstract “hyperobject” it focuses into easier understanding is “high fashion” or “luxury” — which may arguably be the most important function of the “pop up” store in the first place, and it makes sense that the neighborhood’s vast array of pop ups is that for which it has gained great reknown.

But Seongsu's transformation follows a deeper spatial logic. Hurt's research on Seoul's "hot places" identifies what he terms an "urban interface singularity"—the phenomenon that occurs when multiple distinct urban interface types concentrate in a tight geographical space, creating a critical density threshold that fundamentally changes how the neighborhood functions. Like a gravitational singularity in physics, where normal rules break down at extreme density, urban interface singularities create spaces where too many different spatial systems collapse into the same location simultaneously.

Model @gisela.lardin sips coffee inside the TTRS coffee shop that had been directly next door to Cafe Onion, but didn’t establish a real industrial-chic vibe in that design-strong corner of town area and hence has since come and gone. Its sense of industrial-chicness was muddled and confused, at best.

Seongsu achieved singularity status by compressing 8-9 distinct interface types into a relatively small neighborhood:

Urban Interface Types Present in Seongsu:

Type A (Parametric/Adaptive Space): Spaces designed to morph based on user needs, like Daelim Warehouse

Type B (Industrial-Heritage Transition): Former shoe factories and warehouses being converted

Type C (Nth Space/Selfie Studios): Instagram-optimized photo zones and selfie culture infrastructure

Type E (Luxury Consumption): High-end cafés and designer brand showrooms

Type F (Commercialized Youth Zone): Fully commercialized district with high foot traffic

Type G (Temporal Popup): Constant rotation of popup stores—reportedly 40-60 per week

Type H (Underground/Hidden): Back-alley venues and insider-knowledge spaces

Type D (Adjacent Traditional Residential): Borders traditional Seoul Forest neighborhood areas

This isn't just variety—it's interface density approaching critical mass. Research on Korean hot places shows that neighborhoods become destinations not because they represent a single aesthetic, but because they contain high concentrations of multiple interface types in close proximity. Seongsu compressed more interface variety into a smaller space than almost anywhere else in Seoul, creating what Hurt describes as maximum spatial affordance for diverse aesthetic performances and cultural production.

The singularity effect explains why Seongsu became such a powerful "aesthetic laboratory"—with 8-9 different spatial systems operating simultaneously in the same few blocks, the neighborhood enables more varied cultural performances and attracts more diverse users than single-interface neighborhoods. It's the compression itself, not any single element, that generates the neighborhood's outsized cultural influence.

A visiting tourist, a consultant from Singapore, who had heard about the place and its unique industrial vibes, finsally get a clear moment in front of the coveted front door-as-background for our camera last September. Cafe Onion is easily the most famous and always-filled cafe in Seongsu-dong, and which is tha flagship cafe of the area’s industrial history and contemporary vibes. It will also likely one of the few to actually survive what is to come.

Café Onion became the face of this transformation. The coffee shop that opened in 2016 in a converted 1970s metal factory—previously a supermarket, restaurant, and repair shop—became Seongsu's defining image almost immediately. With its preserved red brick walls, raw concrete surfaces, and industrial steel framework left deliberately exposed, Café Onion turned Type B (industrial-heritage transition) into an Instagram phenomenon. The rooftop terrace overlooking factory buildings and railroad tracks, the minimalist furniture against rustic textures, the queues of 50+ people on weekend mornings waiting for Pandoro bread dusted with powdered sugar—it all became instantly recognizable shorthand for "Seongsu aesthetic." Travel blogs called it "the hippest café in Seoul." Design magazines featured it as exemplifying the "Brooklyn of Seoul" transformation. It became impossible to think about Seongsu without picturing Café Onion's industrial-chic interior.

Cafe Onion’s (@cafe.onion) infamous pastries do most of the talking on social media across the planet.

Model @ynana5663 highlights the interior of the factory wall that aestehtically grounds the cafe in the past that gives it context and cool cred, while also being eminently Instagrammable. What was particularly interesting for us here was mixing the sunlight streaming in onto our interior that was also exposed to the outside (making it also an exterior), while compensating with flash, which brought out the history quite literallywritten into the walls of the place. The remains of the old company name “신일금속” Or Shinil Metals still insistently beckons to remain legible all around the building. One cannot forget what this place once was.

But that iconic status reveals the paradox. Café Onion succeeded by preserving industrial authenticity—the worn walls, the factory bones, the sense that real manufacturing happened here. Yet its very success as an aesthetic destination made the neighborhood valuable enough to demolish the actual industrial buildings that gave it character. The café became famous for adaptive reuse of a factory, while redevelopment plans call for erasing the factories entirely. What Café Onion preserved as aesthetic choice, the redevelopment machine eliminates as economic necessity. The workshop owners facing eviction in 2025 occupy the same industrial buildings that Café Onion romanticized in 2016—except they're still actually making things, which makes them obsolete rather than photogenic.

Model @raqulaaa boldly squats in a pose right in the main sitting room of the cafe, where we used a tightly zoomed-in flash burst to hit her with a short 1-2-3 burst that, while visible, didn’t really bother, since it’s the wide spread of most normal flashes that cause people to take notice. Also of note is Cafe Onion’s seemingly lax policy towards camera use inside and around the place. It been one of the most popular venues in the entire city of Seoul, they have decided to go the opposite route of most places and actively ignore even the most professional of camera, rigs, especially since Chinese vloggers with pretty advanced rigs are constantly filming outside the front door, and the café obviously knows it's a major Instagram destination, and has made great use of the placement of their cakes and confections and the industrial remnant of the building to allow its unparalleled Instagrammability to keep the place packed and their commercial coffers filled. This picture is evidence of a very different approach to photography than 99% of the other popular places in Seoul.

This authenticity was real, in its way. The industrial buildings were genuine—Seongsu had been Seoul's light manufacturing district for decades. The small workshops making shoes, bags, and leather goods were the original tenants. The neighborhood had texture, history, human scale.

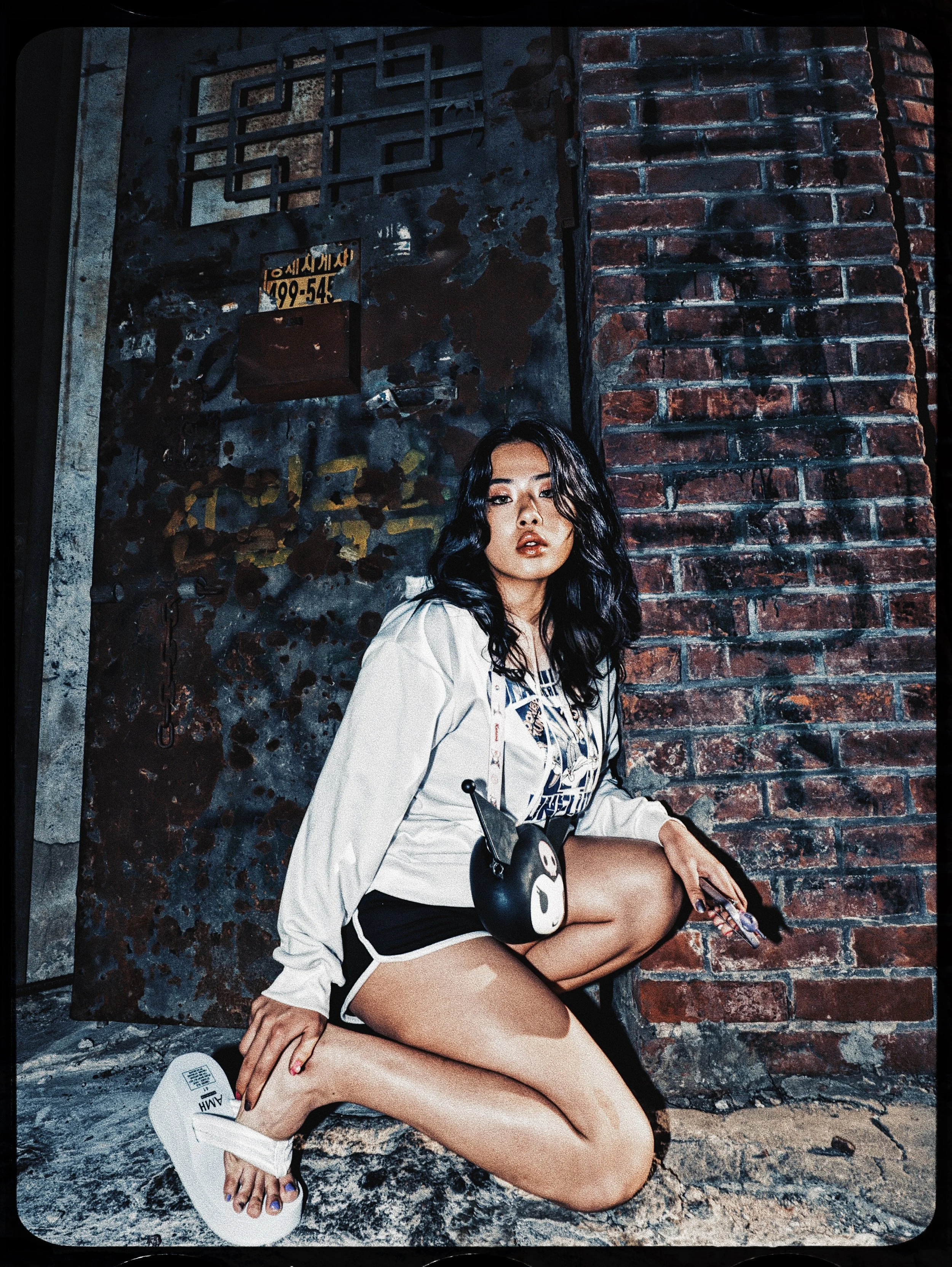

Model @zibi1ooo helps us enter the interior of one of the main strip’s busiest, still-operational machine shops, at which point the only worker inside offered us our opportunity to shoot while taking his own chance for a smoke/phone break.

Which made it perfect for demolition.

Because here's what most people don't understand about Korean redevelopment: it doesn't target failing neighborhoods. It targets succeeding neighborhoods at the exact moment they become valuable enough to justify large-scale reconstruction.

In October 2024, Seoul's Urban Planning Committee approved three major redevelopment projects in Seongsu—documented in official city planning announcements. These aren't renovations. They're teardowns. The 252-15 area near Namseong Station: a 37-story mixed-use complex with 519 apartments and 54 officetels over 110,000㎡, according to the project approval documents submitted to Seoul Metropolitan Government. The 63-1 area: selected for "Rapid Integrated Planning" (신속통합기획, shinsok tonghap gihwek) redevelopment. The nearby Gu-ui Jayang zone: approved after decades of community conflict.

Together, these projects will demolish hundreds of buildings—including those workshops, the small cafés that made Seongsu cool, the galleries where Korean designers exhibit, the artisan studios that give the neighborhood its character.

And they'll replace them with apartment towers that look identical to every other apartment tower in Seoul.

Model @meimalibu_ poses down the block in front of a large advertisement with stark graphics that instantly turned into a studio situation with our powerful portable strobes that is essentially a studio on a stick.

Why This Keeps Happening

The Korean redevelopment system persists because it solves a real problem: Korea's housing stock ages rapidly. Apartments built in the 1980s-90s were often constructed quickly, with quality issues. Industry analyses typically cite a 30-40 year lifecycle before buildings require major renovation or replacement—creating recurring waves of redevelopment that sweep through neighborhoods every generation.

But the solution—wholesale demolition and replacement—creates its own pathologies.

First, it produces cyclical displacement. The people who moved into Sadang's new apartments in 1993 are now facing their own redevelopment wave as those buildings age. Every generation experiences displacement as the neighborhoods they live in become obsolete and get reconstructed.

Second, it erases economic diversity. Redevelopment homogenizes neighborhoods into apartment districts with uniform income levels. The marginal economies—workshops, small manufacturers, artists who need cheap space—get displaced with each cycle. Seoul ends up with less texture, less variety, less of what makes urban life interesting.

Third, it creates what Hurt terms "consumption infrastructure versus lived space" interfaces—a spatial paradox where world-class subway stations operate amid substandard housing, where creative districts exist only in the temporary window between when they become cool and when they become profitable enough to demolish, where neighborhoods become places that everyone passes through but nobody can afford to inhabit.

The Second Death of Seongsu

Workshop owners in the district have started the grim logistics of departure. Some are documenting their spaces—photographing workbenches, tools, the particular quality of light through industrial windows—not out of sentimentality exactly, but because this is how Seoul works. You preserve what you can before it's erased.

One artisan, speaking on condition of anonymity, described his family's trajectory: "My parents were displaced from Jongno in the 1970s during Park Chung-hee's clearances"—referring to the large-scale slum clearances and urban beautification campaigns that characterized Seoul's development under military rule. "They moved to Seongsu because it was cheap and industrial—nobody wanted to live here then. Now I'm being displaced from Seongsu. I'll probably move to some neighborhood in Gyeonggi Province that nobody wants now. And in 30 years, my kids will get displaced from there too."

It's a pattern that reveals the system's true nature: not crisis response, but continuous operation.

The cafés that made Seongsu famous are starting to close too, quietly, without much fanfare. Building owners know what's coming. Why renew a lease when demolition is scheduled? The cool, authentic Seongsu that lifestyle magazines wrote about will exist for maybe another 18 months. Then it'll become a construction site. Then it'll become another cluster of identical apartment towers.

And in 20 years, someone will write a similar article about whatever neighborhood becomes the next Seongsu—the next cool, authentic district full of small businesses and creative people who made it interesting, right before it gets demolished because they made it valuable.

Model @emnitviews poses in a designer dress by freshly-graduated fashion design student @notneomethat had been walked just a week before in the Konkuk University Apparel Design Graduation show. This is in the back alley of a huge coffee shop/restaurant complex that turned out to be an ongoing, huge popup experiment, and all of the places there have since disappeared, though the alley obviously remains.

This is how Korean redevelopment works. It's not a bug in the system.

It is the system.

The Insatiable Machine

There's a term in Korean urban planning: 도시재생 (dosi jaeseong), "urban regeneration." Since the mid-2010s, it's been promoted as the alternative to redevelopment—preservation, renovation, adaptive reuse instead of demolition. Politicians talk about it. Urban planners publish papers on it. The city government announces pilot programs.

But 재개발 keeps winning.

Because the financial incentives are overwhelming. Analyses of Korean redevelopment economics show that property owners who participate in redevelopment can see their asset values triple or quadruple—a return that makes resistance economically irrational for landowners even if it destroys the community. Construction companies make huge profits. Local governments get massive property tax increases. Everyone with capital benefits.

The people who lose—tenants, small business owners, the existing community—have no leverage in the system. They can protest, organize, hire lawyers. Sometimes they delay projects by a few years. But they almost never stop them.

In the past three decades, according to housing policy researchers analyzing Seoul Metropolitan Government data, Korean redevelopment has displaced millions of people across Seoul alone. Every single one of those displacements followed the same pattern: property values rise, redevelopment association forms, existing community resists, city approves project anyway, demolition proceeds, new buildings go up, new population moves in.

The 50+ workshops facing demolition in Seongsu are just the latest iteration of a process that has been running continuously since the 1970s. It will keep running long after they're gone, eating neighborhoods one by one, transforming Seoul into an ever-more-expensive city of nearly identical apartment towers where nobody can afford to stay in one place for more than a generation.

The irony won't be lost on anyone paying attention: developers will almost certainly keep the name "Seongsu-dong" for the new apartment complexes. They'll market them as representing "Seongsu's creative heritage." Marketing materials will likely feature photographs of artisan workshops and industrial-chic aesthetics—the very things being demolished to make room for the towers.

Whether they'll mention they destroyed those workshops to build the apartments is not really a question that needs answering.

That might be the most Korean thing about it.

Model @raqulaaa sites us once again next to the Cafe Onion structure, which helped us roll up an expensive Ducati racing bike loaned to us for a bit by @ducaboy_joker, upon which our model could flip her hair ‘round and ‘round to simulate frenetic speed. The possibilities afforded us by Cafe Onion’s unique spatial options allowed for an incomparable amount of photographic options — as well as sociality — that few other places in Seoul to exist.

This article is based on analysis of public redevelopment documents, community center data, historical records, and background conversations with small business owners in affected districts. Research assistance was provided by AI tools for document analysis, translation, and writing under human direction, following SEOULACIOUS's policy of transparency in digital research methodology. All reporting, analysis, and writing represents human editorial judgment.