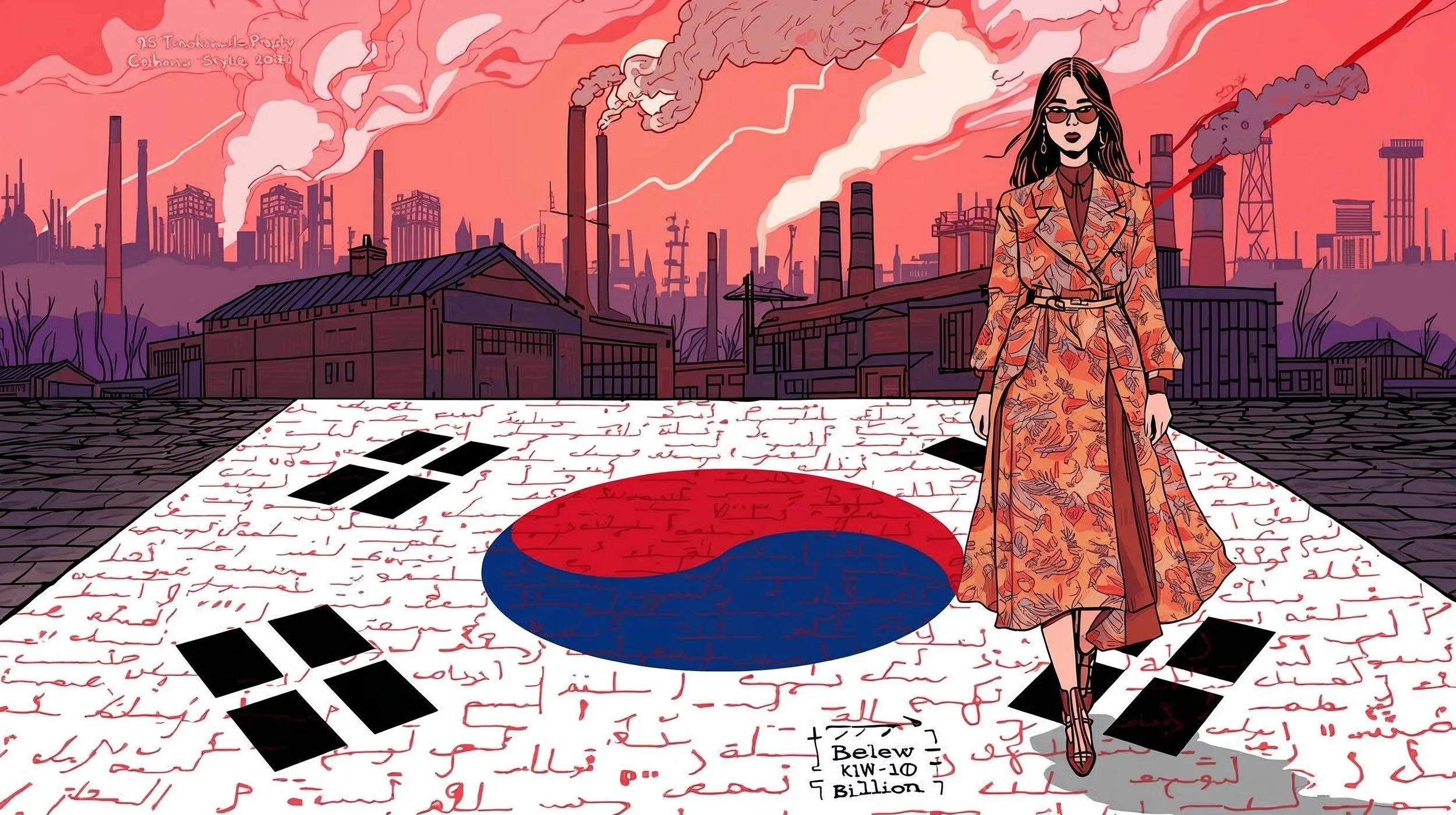

The K-Fashion Paradox: How Korea Conquered Global Style While Its Factories Died

2026 looks to be getting off to a grim start for the Korea textile industry.

CJ Olive Young announced a milestone in early December 2025: over 1 trillion won in purchases from foreign tourists in just eleven months—a figure representing 26 times the 2022 post-pandemic level, according to Korea Textile News (KTNEWS). Foreign customers now account for over 25% of Olive Young's offline sales, up from just 2% in 2022. The company processes 88% of all tax-free cosmetics purchases in Korea, making it what KTNEWS calls an "'inbound export' forward base acquiring foreign currency from around the world."

Meanwhile, Black Friday 2025 delivered what KTNEWS described as "an unexpected reversal"—US consumers spent $11.8 billion online (Adobe Analytics), with e-commerce sales growing 10.4% while physical retail managed only 1.7% (Mastercard SpendingPulse). The secret? AI traffic to US retail sites exploded 805% year-over-year, according to KTNEWS's December 2nd analysis. Korean fashion platforms like Musinsa posted "record-breaking results," with operating profit hitting 706 billion won for the first nine months of 2025.

But walk into the offices of Korea's textile industry newspapers—publications like Korea Textile News and International Textile News (ITNK)—and you'll find completely different headlines: "This Year's Textile Exports Collapse Below $10 Billion Threshold," "Depressed Year-End... Daegu Production Hub on Emergency Alert," "[Q3 Results] Listed Textile/Fashion Companies in Bitter Winter."

Korea is simultaneously dominating global fashion culture and watching its manufacturing base die. This isn't a contradiction. It's a strategy.

The $10 Billion Line

The $10 billion export threshold carries weight beyond mere numbers. Korea first crossed $10 billion in textile exports on November 11, 1987—the achievement that established "Textile Day" as a national industry holiday. In 2024, ITNK reported that textile exports would "barely scrape $10 billion," returning Korea to 1987 levels despite nearly 40 years of supposed progress. The 2002 peak of $16.1 billion now feels like ancient history.

By late 2024, ITNK documented industry-wide survey results showing 50% of textile companies reporting worse performance than the previous year, with 56.3% expecting further deterioration in 2025. Only 12.5% anticipated improvement. "Daegu's textile hub and Gyeonggi's knit district together can no longer endure—they've been driven to a dead end, with companies giving up in succession," ITNK reported in its May 2025 founding anniversary coverage.

This isn't the sexy story. Fashion magazines don't cover yarn prices, dyeing capacity, or factory closure rates. But the textile industry trade press—the unsexy publications that track production infrastructure—have been documenting this divergence for years. While everyone celebrated K-fashion's global rise, these papers watched the factories disappear.

The Geographic Split

ITNK's coverage reveals where Korean textile manufacturing actually went: North Africa is emerging as the "post-Asia" production hub, with Morocco and Egypt absorbing orders that once went to Korean factories. Vietnam continues to dominate Southeast Asian production. When Ilshin Spinning planned a Guatemala factory, it ultimately relocated to Vietnam instead.

The global polyester market is restructuring with China and India expanding dominance. Korea? Barely mentioned in the new supply chain geography.

Here's what this means in practice: When you buy a "Korean" fashion item from Musinsa or see K-pop idols wearing Korean brands, you're almost certainly looking at clothes made in Vietnam, Bangladesh, China, or increasingly Morocco. The "Korean" part is design, branding, and aesthetic curation—not production.

What Korea Actually Makes Now

Korea didn't abandon manufacturing by accident. It discovered something more valuable: You can dominate fashion without making clothes.

KTNEWS notes that what succeeded in 2025 was AI-driven e-commerce and "style-tech"—the digital infrastructure of fashion rather than its physical production. Black Friday thrived despite recession because Korean platforms had invested in AI-powered recommendation systems that drove an 805% explosion in AI traffic. Musinsa's 706 billion won operating profit came from algorithmic curation, not sewing machines.

Olive Young's 1 trillion won from foreign tourists represents a different kind of manufacturing: the production of desire rather than products. The company's success lies in creating a branded retail experience that tourists associate with Korean beauty standards, even though most products could be purchased elsewhere for less.

Korea became excellent at what fashion increasingly is: curating desire, selling aesthetics, building digital infrastructure. It mastered the highest-value parts of the fashion supply chain while offloading the lowest-margin work of actually making things.

The Daegu Emergency

But tell that to Daegu.

Daegu, Korea's historic textile capital, is on what ITNK calls "emergency alert." ITNK's May 2025 reporting noted that Daegu's chemical fiber fabric capacity runs at "around 30%" with dyeing complex tenants at similar levels. "Companies closing or filing for corporate rehabilitation endlessly one after another," according to their coverage.

This is where theory meets reality. When economists talk about "moving up the value chain" or "transitioning to a knowledge economy," this is what it actually looks like on the ground: Empty factories. Aging workers with no replacements. Industrial neighborhoods going quiet.

The formal black dyeing crisis offers a microcosm of the broader collapse. ITNK reported that recession combined with cultural demand for formal black funeral/formal wear created a supply shortage in black fabric dyeing capacity. Korea's cultural specificity—its unique funeral customs requiring specific textile treatments—met industrial hollowing. The specialized knowledge of dyeing formal black at scale is disappearing because there's no economic logic to maintaining it.

The Success Stories (And What They Reveal)

Yet ITNK's year-end coverage documents survival stories. "Companies investing in automation and differentiation technology during the harsh 2024 downturn still succeeded, growing both qualitatively and quantitatively," the publication noted. "Companies that don't give up during downturns, that prepare and invest—opportunities eventually come."

What kind of companies survived? Not the ones making basic textiles for the global market. The survivors specialized in technical fabrics, invested in automation to eliminate labor costs, or pivoted to ultra-luxury markets where "Made in Korea" still commands premium pricing.

In other words: The only Korean textile manufacturing that survives is manufacturing that doesn't compete on manufacturing. It competes on technology, specialization, or luxury branding—competing on everything except the actual work of making fabric efficiently at scale.

The Cultural Conquest

Meanwhile, Korean fashion culture keeps winning.

Miu Miu's viral success story—documented across global fashion press—showed how Korean aesthetic curation influences global trends. K-pop styling creates visual templates that spread through TikTok and Instagram faster than traditional fashion media cycles. Korean beauty standards reshape global cosmetics formulations and marketing strategies.

But here's what's remarkable: This cultural dominance has zero relationship to Korean manufacturing capacity. Korean fashion could lose every remaining textile factory tomorrow and its global cultural influence would continue uninterrupted. The aesthetic authority exists independently of production capability.

This represents something genuinely new in fashion history. Previous fashion capitals—Paris, Milan, London, New York—derived authority partly from manufacturing heritage and partly from design culture. Korea proved you can build fashion authority through pure cultural production: content, algorithms, aesthetic curation, celebrity styling, social media virality.

You don't need factories if you're manufacturing desire itself.

What the Trade Press Sees

The textile industry newspapers aren't celebrating or mourning. They're documenting transformation with the precision of trade publications that understand what's actually being lost and gained.

ITNK's May 2025 founding anniversary editorial noted: "Middle stream—one of the few remaining sectors—barely maintains viability." The publication documented specific operational details: capacity utilization rates, tenant occupancy levels, bankruptcy filings. These aren't emotional assessments. They're technical measurements of industrial decline.

But the same publications track the success stories. KTNEWS documents Olive Young's 9.5 million monthly active users in August 2025, up 35% year-over-year. ITNK notes which companies survived by automating, specializing, or pivoting to luxury. The trade press reports both narratives because both are true.

The Split Continues

Foreign tourists will keep flooding Olive Young. Musinsa's operating profits will keep growing. Korean fashion will continue dominating global aesthetic conversation—through Instagram algorithms, K-pop videos, TikTok trends, AI-powered style recommendations.

But the factories that once made Korean clothes? They're in Morocco, Egypt, Vietnam—anywhere production still makes economic sense.

Korea conquered global fashion by learning to sell everything except making clothes. The country that once built its textile industry into a $16 billion export powerhouse discovered that manufacturing desire is more profitable than manufacturing garments.

Whether that's triumph or tragedy depends on which industry newspaper you read: the consumer-facing publications celebrating cultural dominance, or the trade press documenting factory closures. The Korean textile industry papers report both. They understand that success in one domain can coincide with collapse in another—that you can win the culture war while losing the manufacturing war, and these might not be contradictory outcomes at all.

They might be the same strategy.

Sources: Korea Textile News (KTNEWS), International Textile News (ITNK), December 2025 coverage; Adobe Analytics; Mastercard SpendingPulse; CJ Olive Young corporate announcements; Musinsa financial reports.